Tucked in among Lungtan's (龍潭) pond-studded, Hakka-cultivated tea gardens, with their commanding vista of the mighty Tahan River (大漢溪) and the purple peaks of the majestic central mountain range beyond, is the Taoyuan Culture Workshop. A week ago, a small crew of young people were preparing the final draft of Taiwan Spirit (台灣精神), a lecture to be given by writer Chung Chao-cheng (鍾肇政) to audiences in Tokyo audiences Saturday at the invitation of the Taiwan Association in Japan (在日台灣同鄉會).

Sixty years ago, Chung Chao-cheng lived in this same Hakka village. He was Shoo Choo-sei, a 20-year-old military conscript recently rescued by war's end from Japanese boot camp. For Chung and many other like-minded Taiwanese, the end of Japan's imperial dreams launched him on an odyssey through several ethnic identities that was to last a lifetime.

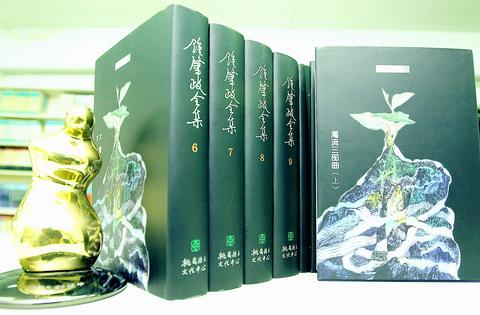

PHOTO COURTESY OF AVANGUARD PRESS

The town is just an hour's drive southwest of Taipei, but in 1945 the town of Lungtan was a frontier fastness far removed from the urban centers of power and at the northeastern-most edge of Hakka cultural advance. This is where Shoo grew up, and where he showed the scholastic promise expected of the only son of a school principal. But his aspirations to become a writer seemed to come to a full stop with the end of the war, in which Shoo become Chung, and the linguistic environment in which he lived was completely altered.

PHOTO: GEORGE TSORNG, TAIPEI TIMES

Since he could speak Japanese and Hakka (but not Mandarin), Chung might have been sorry to see the Japanese leave. Not so. "I was glad. I was very conscious that I had some vague racial bond with our distant cousins living in what we called our `ancestral country' (祖國) -- the very people my Japanese teachers went to great pains to denigrate as dirty, barbaric, uneducated, superstitious, duplicitous, and so on. At the same time, even while embracing Taiwanese as `imperial subjects' (皇民), they made it manifestly clear on a daily basis that we, too, were inferior to Japanese."

So, with the arrival of the Nationalists in late 1945, Shoo/Chung was more than willing to welcome his Chinese brethren, not least because they had shared a common enemy. At first, use of the term "liberation" (光復) used when Taiwan passed under Chinese rule went without challenge.

But not for long. The liberators were soon pillaging and plundering and quickly replaced the Japanese as despised conquerors. Their excesses soon became unbearable and by early 1947 discontent poured out into the streets -- an event remembered as the 228 Incident (二二八事件). Part of the state-directed orgy of killing that followed was selective, with young men boasting Japanese educations singled out as special targets. Chung fit the profile perfectly. He survived, but would never again be able to think of himself as Chinese.

The post-228 bloodletting was but the death blow for Chung's already much-beleaguered Chinese identity.

"By the way they acted, it was clear that we Taiwanese were not considered to be `true Chinese.' All too soon we saw that we were saddled with yet another foreign regime of occupation, and that maybe we had been too hasty in saying `good riddance' to our Japanese masters," Chung recalled.

This is not to say that Chung's conversion from Japanese to Chinese to Taiwanese marked him for martyrdom. He kept his thoughts concerning his ethnic and national identity secret. Many took to the streets to demonstrate, but without Chung. With his signature candor, he says simply: "I was too afraid." Giving questions of nationalism wide berth, he turned to fiction. Running through many of his early stories is the redaction of everyday themes through the eyes and voices of commoner protagonists. In Tea and Peanut Brittle, one of his earliest stories to achieve national notice, the reader is allowed a glimpse into the mysteries of the afterlife, as regarded by two pre-adolescent brothers.

"Papa, drink your tea!" said Ah-tien.

"Papa, go ahead and drink it," said Ah-niu along with him.

Two plastic cups filled with tea had been placed before the bricks, on which a few words were written: "The tomb of Mr Lin Shih-mou." Thus begins a simple story with an uncomplicated message conveyed through unadorned dialogue. When Papa does not partake of the tea, or even the peanut brittle of which he was so fond while still in this world, they are left with some hard questions. What to do with the untouched tea and peanut candy? What happens when one goes to meet the Maker? -- universally understood themes, to be sure, but rendered in a down-home Hakka idiom placing them squarely within the art form now celebrated as "native literature" (鄉土文學). Today Chung is frequently cited as the first creator of a real local product.

But "I did not coin the term `native literature.' Nor did I take part in the [native literature] debate [of the late 1970s]. I was writing the literature, they were debating it."

Yeh Shih-tao (葉石濤), a professor at the Taiwan Literature Research Institute in Tainan and author of a formative history of modern Taiwanese literature, is quick to agree with Chung's thinking. "I did take part [in the native literature movement] -- until I realized that the champions of native literature were in fact promoting `Chinese' literature. Theirs was a political agenda and the real clash was over independence-unification issues. Chung, on the other hand, was too busy crafting his fiction and editing his literary magazine [to become involved]."

Somehow he managed to feed his five children by teaching in primary school, while burning the midnight oil and honing his craft.

A half-decade of dogged effort finally paid off with the publication of a short story in 1951. Once the culture czars sitting in editorial rooms followed martial law into history in 1987, the way was clear for him to publish just about anywhere he liked. His star has been on the ascendance ever since.

Chung's acceptance by literature buffs has been seconded by officialdom. As chief executive of Taoyuan County, Annette Lu (呂秀蓮) referred to Chung as a "giant craftsman of the literary scene (文壇巨匠)." Accolades at the national level had only to await Chen Shui-bian's (陳水扁) accession to the presidential seat. In his first round of political appointments, Chen made Chung one of his 23 presidential advisors.

This presidential affirmation has made him the pride of the Hakka community; he is the one Hakka writer whose fame reaches far beyond literary and intellectual circles.

Li Chiao (李喬) -- after Chung, Taiwan's best-known Hakka fiction writer -- rates Chung as "the greatest of the [post-war] first-generation writes. He was the first to overcome the problem of having been educated in Japanese and mastering Chinese. And, where wartime predecessors like Wu Chuo-liu (吳濁流) gave up on Japan by looking to China for solutions, Chung created a new archetype by looking instead to local roots."

Moreover, "he was a leader, constantly encouraging green writers like myself to do better. If, as editor, he had to send out a rejection letter, it was replete with suggestions for improvement," added Li. "He has refined a narrative style that is at once professional and at the same time deceptively simple. It is the realism of the idiom of daily life that he has rendered into an art form new to the Taiwan literary scene."

For Professor Yeh too, Chung ranks as the "foremost post-war writer," partly for his prodigious output (Chung's own ledger shows almost nine million words of published fiction, six million words in fifty translations, and another six million words of correspondence), but also for his having established the epic novel as a Taiwanese art form. Indeed, Avanguard Press's (前衛出版社) general editor, Chiu Chen-jui (邱振瑞), says that it is for his 1968 Taiwanese Trilogy (濁流三部曲) that Chung is most remembered. But Yeh believes that his short stories deserve greater attention.

Chung's preeminence in the pantheon of postwar writers would probably be misplaced if Taiwanese literature is considered a sub-set within Chinese literature. What, then, sets Taiwanese literature apart from its Chinese counterpart?

Chung's reply is of a piece with his down-to-earth character -- simplicity itself. It is "literature written by Taiwanese." In a foreword to Avanguard Press's Taiwan Literature Series (台灣作家全集), however, he goes further: "Taiwanese literature is the literature of blood and tears, the literature of the people's struggles."

Li points out that "`Chinese' writers can be identified by their worship of the written word," and there are many critics who have dismissed works Chung as having no literary merit on the grounds that his "Chinese is lousy."

For English-speakers unable to appreciate Taiwan literature in the original, we might look to English and American literature for a parallel. Think of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, and of how Mark Twain's work was contemptuously dismissed as "beneath literature" by those contemporaries who were steering by the stars of English literature. In Chung's stories the plot primarily develops through a patois that bears not much more resemblance to the parlor parlance of the Beijing pundits than Huck Finn's.

Now 76, Chung says his writing days are over. "I would love to develop the many stories bouncing around in my head, but I am afraid they will go to the grave with me. I have laid down my pen for good." But he still has plenty to say. According to tour organizer Robert Lu (盧孝治), Chung's conception of the Taiwan spirit, which will be the focus of his talk, is one "consisting primarily of a maritime character, immigrant society become localized over four hundred years, and a readiness to risk danger." It is this spirit that will ultimately make its mark through the words of his characters, who have now found artistic immortality.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she