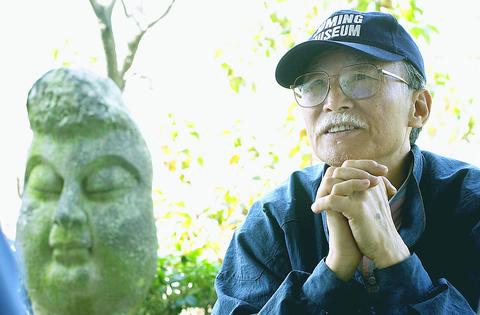

Basking in the sun on the expansive deck of his villa set in the lush valley above Taipei's National Palace Museum (故宮博物院), the sculptor Ju Ming (朱銘) has the calm air of a man who spends his time reflecting on a life of shining achievements. But looks can be deceptive.

Ju, one of Taiwan's most internationally acclaimed artists, is, in fact, still a full-time sculptor despite his age, 63. And by full-time, Ju means 24 hours a day.

PHOTO: MAX WOODWORTH

"Art is not something I can turn off and on. It's me. It's my whole being," Ju said in a recent interview.

PHOTO: MAX WOODWORTH

Indeed, behind his composed exterior, Ju is a tightly-contained bundle of energy, which, he says, unwinds explosively when he sets out to carve one of his monumental Taichi sculptures or his more earthy Living World series sculptures.

And if Ju's works tend to be massive, so is his disdain for much of the art produced in Taiwan nowadays, which he said reflects the lack of just the kind of "leisurely" approach to art that he possesses. When pressed for reasons behind this state affairs, he repeats the often-quoted refrain that the country's education system stifles creativity and forces conformity.

PHOTO: MAX WOODWORTH

"Sometimes you see an artist's credentials on paper and think, `Wow! This person studied in Paris or wherever.' But then you have to look at the names on the works to figure out who did it, because they have no individual style," Ju said.

PHOTO: MAX WOODWORTH

Some artists, Ju added, are left confused by cultural disorientation. A friend, for example, complained bitterly that his works had been criticized as "neither Chinese, nor Western." Ju replied simply by saying that the works then were a good reflection of Taiwan, which he described as a "trash heap, with all sorts of detritus that has come together to make our culture."

If Ju has little love for Taiwan's educational system, it is apparently because it did little to bring him where he is now, respected around the world for his art, the founder of a museum dedicated almost entirely to his own works and famously rich.

PHOTO: MAX WOODWORTH

Small beginnings

PHOTO: RICK CHU, TAIPEI TIMES

For all of his accomplishments, Ju credits first of all himself for having stuck with his art through hard times, but he also attributes much of his success to his mentor Yuyu Yang (

Life changed irrevocably for Ju when, on impulse, he rang Yang's doorbell in 1968. "I just showed up at his door not expecting anything. I was a country boy and he was a great artist. We were like the sky and earth, polar opposites. But still he took me in," Ju said.

PHOTO: CHEN CHENG-CHANG, TAIPEI TIMES

The encounter with Yang would mark the beginning of a career that would see Ju quickly outgrow his small-town beginnings and take his works -- in particular his daunting Taichi figures -- to exhibitions around the world.

Indeed, Ju's early years provided few hints of the fame and fortune to come. He was born into a family of extremely modest means in Tunghsiau (通宵), Miaoli County, in 1938 and admits with a wry smile that he was "a miserable student."

He began sculpting almost by chance, when his father recommended him to a master sculptor named Lee Chin-chuan (

"After stinking so bad at school I was really happy to finally have work," Ju said.

But Ju's steps along the path to becoming a sculptor of world renown were not all as fortuitous as his first one into Lee's workshop. In his twenties, Ju opened a commercial sculpture studio in Tunghsiau, carving on commission mostly for local temples. Financial success left him dissatisfied and, perhaps most importantly, was soon followed by financial collapse. At 31, Ju was back at ground zero contemplating his next career move and hoping to become, what he called a "genuine artist," in contrast to the journeyman work he had been doing until then.

That was when he went looking for Yang. The famed sculptor lived in Taipei, but for Ju he mostly existed as an exalted figure in his imagination, having reveled at his works for years while leafing through now defunct art magazines like Asia (

But through a combination of tenacity, confidence and pure luck, Ju wound up at Yang's doorstep, asking his idol to be his teacher. Amazingly, Yang accepted and their relationship developed along traditional mentor-student lines, with Yang initially offering little advice and mostly observing his understudy.

"He was watching me the whole time, trying to see if I was a good person or a bad person," Ju said. Yang was won over by Ju's down-to-earth and affable personality and the two worked together for nine years.

It would be difficult to underestimate the indebtedness Ju feels toward Yang, as he recalls the most important lesson learned under his teacher which would come to characterize his life as an artist. "The first piece of advice Yang gave me, and one I'll never forget, was when he said `Do not copy my style. Do your own thing.'" So, under the watchful eye of his doting mentor, Ju set out on his own artistic soul-searching, carving the pieces that would provide the foundations to his distinct style.

Art as life

Walking the grounds of the Juming Museum (

Most stunning are the monumental Taichi series (

The Taichi series was conceived from Ju's self-professed principle of "art from leisure."

"Art is not in your mind. It's in your being and no single minute of your life is an exception," Ju said. He sees art as springing from a person's full self, as opposed to skills which can be called up at the time of execution. In this sense, art then represents not just an idea, or a theme, but what Ju says is simply "life."

Ju is also quick to point out that the Taichi series did not arise from an intellectual inquiry into Taoism or Buddhism. "I don't understand any of that stuff. Religion is way over my head."

"Teacher Yang told me I was physically weak and recommended taichi. I took it up and got so absorbed in it, it was all I could think about. So with only that in my head, it was only natural that I begin sculpting the taichi figures."

The sculpted taichi boxers are portrayed frozen in the many different stances of the Chinese exercises and so are often given the titles according the maneuver being performed such as Single Whip Dip (

Made of bronze, using styrofoam and wood molds, the Taichi series works confound the senses by being at the same time massive and dynamic. The delicate balance of the sculptures is a reflection of Ju's near obsessive practice of the exercises.

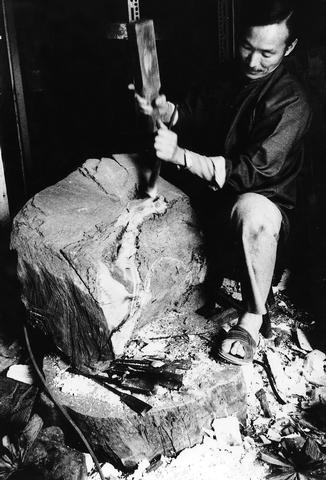

They also reflect Ju's sculpting technique, which he describes as "fast and furious."

"It's not a question of rationally thinking out a work. The brain can't keep up with my knife. I get lost in the motion so that thought becomes irrelevant. It's beyond my control once I start hacking away," Ju said.

Ju has also abandoned the detail that would indicate technical mastery and instead has reduced his figures to faceless forms achieved with the fewest number of strokes necessary while still retaining the integrity of the boxer's body.

"Ju's Taichi series aims to create figures that are larger than life, almost iconic. In doing so, he achieves a universality with the forms," said Johnson Chang (

"Ju strives for free-flowing, free-spirited strokes and a sweeping touch. It's a very Asian approach, with spontaneity in execution and the process as the ultimate expression of the art," Chang said.

These themes, despite their Asian origins, apparently resonate across cultures, as the Taichi series has proven a massive hit in exhibitions in Japan, the US, France, Luxembourg, and, most recently, Belgium. The next stop for the sculptures will be Berlin.

Affirmation of life

Even more expansive than his Taichi series, however, is Ju's Living World series (

In a drastic departure from the pared-down bareness of the Taichi series, the Living World series aims for just the opposite: an intricate and detailed study of individuals. The objective, however, is to approach the same theme of universality through an affirmation of the difference of each person.

"The Living World series is about people and personalities and life's fundamental and basic activities," Chang said.

The works are typically made of wood and come in a wild variety of shapes. Some are wall-sized wooden panels with rows of carved people, each one different, arranged side by side in a geometric pattern. Crudely painted and carved with rough, abrupt strokes, the pieces appear oddly organic, as if the figures grew out of the wood, as opposed to being carved into it. Other pieces in the series include squat human figures dressed in traditional Chinese garb and also executed without unnecessary strokes. In their angular features, the sculptures look similar to early computer graphic renditions of people..

The setting of the Juming Museum is ideal for taking in the pieces, which are placed for the most part outdoors on the perfectly manicured grounds. Visitors step out of a reception area and into an expansive park where the larger works, including the stunning Parachutists, made paradoxically of steel, appear to hang in the air. Smaller works are dotted around the corners of the park. Some are half obscured by shrubs, like children playing hide and seek, while others occupy benches. Some are barely distinguishable from the large stones that dot the landscape, with only a few lines hinting at the form of a human face or an ox's head.

The size of the grounds also allows crowds to disperse so that the pieces can be enjoyed in relative silence. But if crowds are thin, this was not in the original design of the museum.

Calvin Ju (朱原利), son of the artist and director of the museum, concedes that less-than-overwhelming attendance is a primary factor in the museum's strained financial state. About 200,000 people visit the museum a year, bringing in about NT$40 million. "With higher attendance in the summer and annual fees for members of the Juming Arts Education Foundation (朱銘文教基金會) we manage to just break even," Calvin Ju said. The museum has also sunk much of its money into expansion projects, as it aims to grow by about 40 percent over the next few years.

Ju established the museum in Chinshan for several reasons. The first, in what may have been a miscalculation, was its proximity to Taipei so that international visitors can reach the site for a day trip. Ju also favored the plot of land for its size and, in a quintessentially Chinese manner, liked the fact that it had "mountains and water."

But the museum was also conceived with more than commercial considerations in mind. It was also a desire to keep his works in Taiwan and exhibit them for art lovers on the island. Another envisioned function was to provide a space to boost arts education through the association which takes his name by means of hands-on art days for children and other activities.

Always a precarious venture as a private institution, Ju's museum nonetheless reflects the grand scale on which the artist sees his life and his works, and exemplifies his overpowering confidence.

"Yang always told me to be myself and not worry about studying," Ju said. "In Taiwan, the best artists are probably all unscholarly like myself."

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.