Private Yoyama sat low in the foxhole, his tan, sweat-soaked uniform weighing heavy on his shoulders. He barely noticed the mosquitoes pricking his neck because of the sight coming into view down the barrel of his rifle, a battalion of Chinese soldiers.

"This was war," he says, excited, "and they didn't know I was Chinese -- from Taiwan. They could only see my Japanese uniform and the Rising Sun flag behind me. To them I was just another Japanese regular and they wanted to kill me."

Yoyama had been trying for years to resolve what to do if his service in the Japanese army brought him to this. Should he shoot at the ground, into the air, or to the side? The decision, however, exploded on him with the first mortar shells that landed.

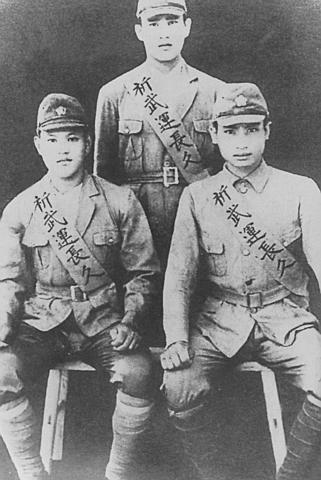

Photo: courtesy of li shen-chang

"I didn't know what to do," recalls Yoyama, "I didn't want to shoot the Chinese soldiers, but when the shells started bursting around me, I pulled the trigger and I didn't stop until it was over. I was shooting for my life.

The Japanese government drafted Yoyama, or known better today by his Chinese name, Yeh, into the Imperial Army as the war waned into 1944. Things were going badly for Japan by then, and sending him to China was a desperate measure.

Troops from the Japanese colony of Taiwan were not supposed to fight in China, Yeh says; they were usually sent to Southeast Asia -- the Philippines, Vietnam, Singapore, and Indonesia. Sending Taiwanese troops to China was considered risky because they might refuse to fight, or even worse, turn spy.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF LI SHEN-CHANG

"But if I knew what they [the Chinese army] were going to do when they came to Taiwan [after the war], I would have aimed more carefully," he says, trembling with rage.

Many elderly Taiwanese men share Yeh's sentiment, especially those who remember the good times under Japanese rule and the horror of the 2-28 massacre following the Nationalist (KMT) government's arrival on Taiwan.

According to historians, during their 50-year rule of Taiwan, 1895-1945, the Japanese hoisted the island into the modern world, laying hundreds of miles of railroad tracks, building modern harbors and roads, and in 1903, the first hydro electric generators in Asia outside of Japan.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF LIN A-CHIEN

The level of development prompted one scholar to remark, "the average citizen in Taiwan lived far better than people in any province of China at the time."

"The Japanese government was very good to people here," says Yeh. "They gave us a good education, jobs were easy to find, they built roads and other infrastructure. ... So when they ordered me to war, I went."

Yeh didn't go alone. In all, more than 200,000 Taiwanese served in the Japanese Imperial Army or Navy, though only half that number were actually packed off into warships and sent to battle. The other half worked as hospital attendants, laborers or at other non-combat jobs.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF WU CHING-HO

Of the ones who did go, some 30,000 died fighting to maintain the Empire of the Rising Sun, including former President Lee Teng-hui's (

And Japan has honored those who fell. Every one of His Emperor's Taiwan forces killed in battle was given a ceremonial burial in Tokyo's Yasukuni shrine, a Shinto memorial to Japan's war dead.

Yasukuni shrine also holds the remains of the 30 Taiwanese convicted and hung for war crimes. Historian John Copper notes that some Taiwanese did serve in "units that committed atrocities against Chinese in Nanking and elsewhere."

But not many soldiers here remember it that way. At least, not the five men who agreed to an early morning story-telling session at one of Taipei's parks. Meeting in a grove of trees, just as the cicadas awoke, they chitchatted about the past before issuing their only precondition: no (Mandarin) Chinese.

"I haven't spoken a word of Chinese in 55 years," laughs one of them, a tall man with a white rim of hair on an otherwise bare head. Dressed in a pair of boxers, white undershirt and brown shoes, he says his name is Lee.

"After what they did to us," he says of the KMT troops who came to Taiwan after WWII, "I refuse to speak Chinese. I only speak Taiwanese and Japanese," he says and pokes his wooden cane into the ground to emphasize the point.

The former soldiers then proceed to describe life in Taiwan under the Japanese, agreeing that life was good here and that other than the police -- whom they hated -- they held deep respect for their former colonial governors. They even prod their new found American interrogator about long sleepless nights when American bombers dropped their payload on Taiwan, bombs that destroyed landmarks like Taipei Main Station (

"I was proud to volunteer and serve in the Japanese army," says Amano Mazuo, who wants only to be identified by his Japanese name. He joined in time for the invasion of the Philippines and maintains that life in the army suited him. "To this day, I'm proud of it."

Questions of war crimes committed by the Japanese do little to shake Amano's benign memories. What about the comfort women, war time atrocities and treatment of war prisoners in the Philippines? Despite mountains of testimony by Philippine and US soldiers that is described to him in detail, Amano insists he never saw anything that would lead him to believe such things. "Japanese soldiers were very disciplined, I don't think they would torture anyone," he says. "At least, I never saw it."

"I don't think anyone was treated badly," he adds. "Japanese soldiers didn't have much -- we were mostly fed watered down Miso soup at meal time, and the prisoners were given the same. Maybe to them it wasn't enough. Maybe they thought conditions were bad, but in reality, they lived under the same conditions as we soldiers did."

"Why," interjects Lee at one point, "do people always bring up the mistreatment of American soldiers during the war? What about Japanese prisoners of war? We often hear the tale, `Japanese soldiers never surrendered. They would rather die than face shame' and other such nonsense. Thousands of Japanese soldiers were captured by Chiang Kai-shek's (蔣介石) army, and they were tortured and killed -- what about them?"

The day is heating up now, sweat drips freely from the old faces and the cicadas seem deafeningly loud. The group begins talking in Japanese amongst themselves, arguing points of each other's testimony. They suddenly stop and one points out that the majority of them never left Taiwan, that they should talk more about what happened here.

So they describe wartime Taiwan, the munitions factories and extensive training grounds set up throughout the land and the number of Japanese soldiers, more than 160,000, shipped off the island after the war. It was this large number of troops here that made the Allies decide to bypass a Taiwan invasion in favor of Okinawa, they say.

Talk soon turns to the days just after the war. They agree that initially, they rejoiced at being returned to China. Such good feelings, however, did not last.

Taiwan's 2-28 peace museum contains one striking photo of Taiwanese citizens welcoming the Chinese troops to the island, waving the white-starred Nationalist flags. It's hard to miss the fact that many in this welcoming committee are wearing Kimono, wood sandals and other Japanese attire.

The schoolteacher, Lee, laughs as he remembers the day Allied troops first arrived at Keelung harbor. US Navy ships ferried the Nationalist Chinese to Taiwan, but once the ships arrived, he says, the Chinese commander refused to disembark. "The American captain told the Chinese commander to enter the harbor but he refused to leave the boat," says Lee with a chuckle. "They were too afraid of the Japanese troops still in Taiwan [which was a substantial force -- more than 250,000 troops, including Taiwanese conscripts]. It wasn't until the captain promised them that the Japanese had surrendered and that American troops were standing by that they agreed to go ashore."

Then Lee becomes serious. He says the only thing he blames America for in WWII is the US transport ships that brought Nationalist troops to Taiwan after the war in 1945 and then the entire KMT government in 1949 after they lost the civil war in China to Mao.

"Some people say MacArthur was a great hero," says Lee, "but I hate him. He dropped the bomb on Hiroshima and he dropped Chiang Kai-shek on us. Chiang Kai-shek was worse than what happened to Hiroshima and Nagasaki; he was inhuman."

Others in the group of men agree with Lee. Their feelings run deep over the end of the war and the Nationalist Chinese troops that came to Taiwan in its aftermath. "Of course we never forgot who we were -- that we were Chinese. We always dreamed of the day China would come and take us back," says one old soldier who requested anonymity. "But when they [the Nationalist Army] came, they were a rag tag group.

"They were rude, unkempt, they smelled, they stole anything they could get their hands on. ... and when they looked at us -- our Japanese clothes, Japanese hairstyles and Japanese manners -- they saw the same enemy they had been fighting for 10 years in China and they hated us. That's why `2-28' happened.'"

The group argues back and forth, that the Nationalists were evil -- or no, not evil but simply angry after surviving a decade long war with Japan that included horrors like the Nanking massacre. Their reaction to Taiwan's Japanese society was a spark, these men say, that led to a later "incident" known simply as 2-28 (2/28/1947) when Nationalist troops massacred at least 1,000 Taiwanese civilians, according to the 2-28 Museum.

Releasing years of pent up anger seems to deflate the group. The morning has faded and the tropical sun is beating down on the group through the palm fronds. It's time to go. Lee wipes the sweat from his brow. He has maintained a `no-Chinese' rule for 55 years and his face sags with the effort.

"Holding on to hatred takes too much energy," says Yeh, the soldier who fought in China. He takes back what he said earlier about aiming more carefully at the oncoming Nationalist troops. He admits he was so scared at the time, he doesn't know what direction his bullets flew.

"You cannot blame people for what happened back then. What happened during WWII was a problem of the time period, not a problem between people," says Yeh in a voice deepening with the emotion and authority of someone who knows.

"I still have a lot of Japanese friends from the war and a lot of Nationalist Chinese friends who came here in its aftermath, and I can tell you this -- no matter what events may pass and who gets the blame, people are pretty much the same no matter where they come from."

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the