Myanmar’s generals have a choice to make following the magnitude 7.7 earthquake on Friday last week.

They can repeat the mistakes of 17 years ago when they refused to allow in international help after Cyclone Nargis tore through the country, leaving 140,000 dead, or facilitate the free flow of urgent assistance.

Determined to keep Myanmar closed to the world, the junta blocked international relief efforts by banning foreign boats and aircraft from delivering supplies and delaying visas for aid workers in the first few critical weeks after the 2008 disaster. It cannot afford to take the same path this time.

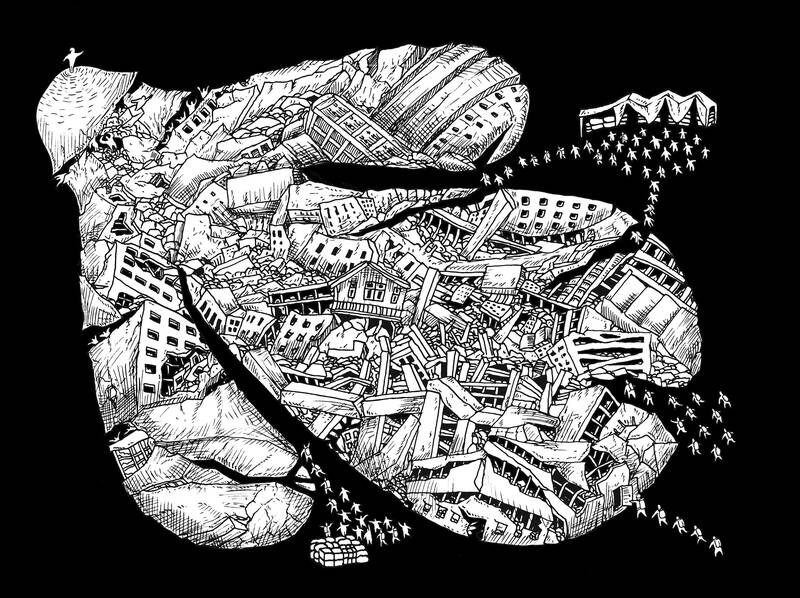

Illustration: Mountain People

Modeling from the US Geological Survey indicates that more than 10,000 people might have died in the quake, and that estimated economic losses could exceed the nation’s GDP.

So far, the generals appear to be allowing some assistance in, although it is not yet clear whether it is reaching areas held by the anti-junta resistance. Severely limited Internet access means there is little information about the true death toll other than the official tally of 2,056, with more than 3,900 injured.

That Myanmar is in the middle of a civil war is complicating rescue efforts and the distribution of aid. The regime, which took power in a coup in 2021, controls less than one-quarter of the country.

India is airlifting a mobile army hospital to Mandalay — the epicenter of the earthquake — along with a team of medics and tonnes of relief supplies. China, Russia, Israel and the UK are also providing assistance, while ASEAN said teams from Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam had been deployed. US President Donald Trump’s cuts to the US Agency for International Development have reportedly delayed and restricted help from the US.

The junta’s acceptance of aid is a significant step, and one that the international community should leverage to pry the doors open further. They also must prevent the regime from exploiting the assistance for its own gain.

Ironically, it was, in part, the junta’s decision in 2008 to eventually allow in foreign aid to deal with the cyclone’s aftermath that led to Myanmar’s gradual opening up, and the eventual election of pro-democracy forces in 2015. Citizens would be hoping something similar happens.

Anti-junta groups and ethnic armies hold the bulk of the territory, along with important infrastructure projects including Chinese-funded oil and gas pipelines and parts of the 1,400km highway that runs from the northeastern Indian state of Manipur through Myanmar to Mae Sot in Thailand.

The National Unity Government, which represents the ousted civilian administration, initiated a two-week ceasefire in quake-hit areas to allow aid to reach victims. It does not look like the junta would do the same. Instead, its warplanes continued to conduct airstrikes near the disaster zones, taking advantage of the chaos to try and gain a foothold against rebel armies.

China, India and Thailand — Myanmar’s three biggest neighbors — have an important role to play, as does the UN, which estimates that 20 million people have been affected by the quake and the magnitude 5.1 aftershock that followed on Sunday.

The EU, the UK, Australia and New Zealand, among others, have announced millions of dollars in aid. The key would be how this is distributed and whether pressure from donor nations and relief groups can convince the junta to give up its four-year-long war against its citizens.

Beijing, in particular, cannot be happy with the chaos on its border, where Myanmar’s army has clashed with armed resistance groups, forcing refugees to flee into China. It is unclear whether a Beijing-mediated ceasefire agreement that came into effect in January will hold.

Rather than prop up the junta, China should support the peace process in other parts of the country that would encourage a stable environment and help protect its investments. That is also a chance to prove its credibility as a global peacemaker, a role it has shown ambitions to play in Ukraine and elsewhere.

The Burmese army, or Tatmadaw as it is known, has perpetuated war on multiple fronts since the nation won independence from British rule in 1948. The earthquake has only exacerbated the humanitarian crisis born out of that generations-long conflict. Even before it hit, about one-third of the population was in need of humanitarian assistance, while the civil war had displaced more than 3.5 million people, including 1.6 million in the crisis-struck areas.

There is precedence for a natural disaster helping to end a long-running conflict. The Acehnese national army — the armed wing of the Free Aceh Movement in Indonesia — demobilized and disbanded a year after the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami destroyed much of the province, ending a 30-year separatist insurgency.

Cyclone Nargis and the tsunami have provided a road map, however imperfect. Myanmar and its backers should use it.

Ruth Pollard is a Bloomberg Opinion Managing Editor. Previously she was South and Southeast Asia government team leader at Bloomberg News and Middle East correspondent for the Sydney Morning Herald. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

The gutting of Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA) by US President Donald Trump’s administration poses a serious threat to the global voice of freedom, particularly for those living under authoritarian regimes such as China. The US — hailed as the model of liberal democracy — has the moral responsibility to uphold the values it champions. In undermining these institutions, the US risks diminishing its “soft power,” a pivotal pillar of its global influence. VOA Tibetan and RFA Tibetan played an enormous role in promoting the strong image of the US in and outside Tibet. On VOA Tibetan,

Former minister of culture Lung Ying-tai (龍應台) has long wielded influence through the power of words. Her articles once served as a moral compass for a society in transition. However, as her April 1 guest article in the New York Times, “The Clock Is Ticking for Taiwan,” makes all too clear, even celebrated prose can mislead when romanticism clouds political judgement. Lung crafts a narrative that is less an analysis of Taiwan’s geopolitical reality than an exercise in wistful nostalgia. As political scientists and international relations academics, we believe it is crucial to correct the misconceptions embedded in her article,

Sung Chien-liang (宋建樑), the leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) efforts to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Legislator Lee Kun-cheng (李坤城), caused a national outrage and drew diplomatic condemnation on Tuesday after he arrived at the New Taipei City District Prosecutors’ Office dressed in a Nazi uniform. Sung performed a Nazi salute and carried a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf as he arrived to be questioned over allegations of signature forgery in the recall petition. The KMT’s response to the incident has shown a striking lack of contrition and decency. Rather than apologizing and distancing itself from Sung’s actions,

US President Trump weighed into the state of America’s semiconductor manufacturing when he declared, “They [Taiwan] stole it from us. They took it from us, and I don’t blame them. I give them credit.” At a prior White House event President Trump hosted TSMC chairman C.C. Wei (魏哲家), head of the world’s largest and most advanced chip manufacturer, to announce a commitment to invest US$100 billion in America. The president then shifted his previously critical rhetoric on Taiwan and put off tariffs on its chips. Now we learn that the Trump Administration is conducting a “trade investigation” on semiconductors which