With only a few weeks to go before the federal election on Sunday, Germany experienced a political earthquake. For the first time, the main opposition party, the center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU), relied on the support of the extreme-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) to pass a motion in the national parliament.

CDU leader Friedrich Merz, long seen as a shoo-in for the chancellorship, justified the move by blaming other parties for their unwillingness to address migration. While the motion produced nothing concrete, the democratic political parties’ “firewall” against the far right was breached. No longer could Germany claim to be one of the last major European democracies not to have “normalized” the far right.

What exactly is normalization, and on what grounds should it be criticized? For starters, it is not the same thing as mainstreaming. Normalization is specifically about rationalizing a transgression of an existing norm — not collaborating with far-right parties that pose a threat to democracy, in this case — whereas “mainstream” is always relative. Like the notion of the political center, it has no objective content, but simply refers to what is most common or widely subscribed.

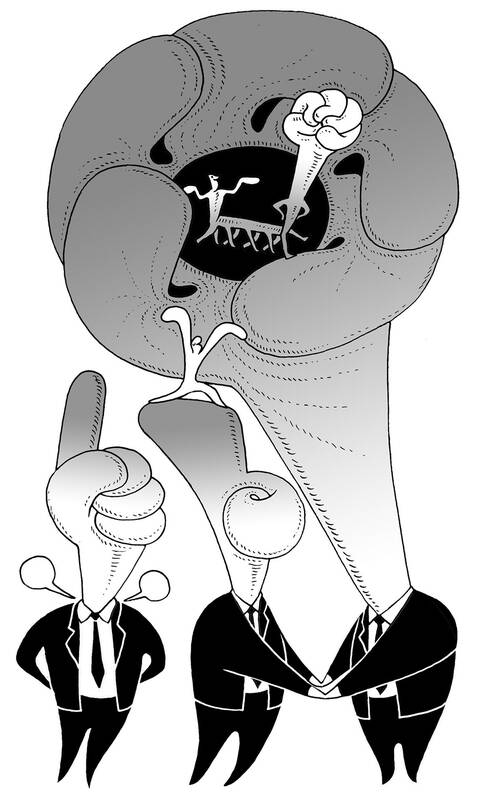

Illustration: Mountain People

Thus, entering a coalition with a far-right party, or relying on it to pass laws, is a form of normalization, while copying the rhetoric of the far right is an example of mainstreaming. To mainstream an issue is to call attention to it and frame it the way the far right wants it to be framed. Hence, social scientists have long warned that if the issues the far right favors dominate in an election campaign, the far right would do well at the polls.

Since pro-democracy politicians do not want to be perceived as cynical opportunists, they usually seek ways to justify normalization. One option is simply to claim that the norm remains in force, and that one’s behavior does not qualify as a violation. Merz took this path when he stressed that his goal is to diminish AfD’s share of the vote, but this argument is unconvincing. Rival parties often end up in coalitions, and the fact that they have conflicting programs does not mean that they never cooperate.

Another option is simply to declare the norm invalid. For decades, the Italian Social Movement (MSI), which cultivated nostalgia for Mussolini and fascism, was deemed beyond the pale. Like the communists, it was not considered to be a part of the arco costituzionale (“the constitutional arch”): the parties that basically accepted Italy’s post-war democratic constitution. Then came Silvio Berlusconi, a pioneer of normalization who suggested that the anti-fascist consensus was either obsolete or a left-wing plot against the right. His party proceeded to form a coalition with the MSI in 1994.

One other option is to retain the norm, while insisting either that it does not apply to a particular party, or that it is less important than other political imperatives. Think Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, who got her political start in the MSI’s youth organizations. Plenty of politicians, inside and outside Italy, have decided that her Brothers of Italy party — a direct descendant of the MSI — is a perfectly acceptable partner. Even those still hesitant to work with the most right-wing Italian government since World War II could invoke larger issues — such as the need to present a united front in support of Ukraine — to justify cooperation.

A similar logic applies in Austria, where the center-right Austrian People’s Party (OVP) had initially ruled out working with Herbert Kickl, the chair of the far-right Freedom Party (FPO). After coalition talks with the center-left failed, the OVP proceeded to negotiate with Kickl’s party, all in the name of keeping Austria governable. These talks, too, have now failed, but, in the process, the OVP signaled to Austrians that Kickl was an acceptable choice after all (a signal that no doubt would help the FPO in the next elections). It is reasonable to assume that many Austrians voted for the OVP in the most recent election precisely because it had vowed not to normalize the far right; it is unclear whether it would be trusted again after its glaring betrayal of that promise.

Even more nefarious are situations where the far right calls the shots even as its leaders remain out of high office, and thus largely unaccountable. In Sweden, for example, the current minority government is supported by the far-right Sweden Democrats; in France, the government — which also lacks a majority — is ultimately at the mercy of Marine Le Pen’s National Rally; and in the Netherlands, the government includes the far right, but its leader, Geert Wilders — who completely controls his party as its only official member — remains in the background.

Normalization is easier to detect than mainstreaming, but recognizing it as a problem requires a public that is paying attention and prominent figures who would make norm-breaking a scandal, instead of normalizing it. Voters take their cues from elites; if a politician who is seen as mainstream treats a party as normal, public opinion tends to follow. Moreover, research has shown that such acceptance spreads beyond partisans of the mainstream party that started the process and eventually extends to the citizenry as a whole.

Once normalization has happened, it is virtually impossible to undo. The significance of mainstreaming is somewhat different, because it remains up to politicians which topics to emphasize and how to treat them. It is high time they learned that uncritically adopting far-right talking points — often thinly veiled incitements to hatred — is not only immoral. It is also a losing proposition at the ballot box.

Jan-Werner Mueller, professor of politics at Princeton University, is the author, most recently, of Democracy Rules.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

I came to Taiwan to pursue my degree thinking that Taiwanese are “friendly,” but I was welcomed by Taiwanese classmates laughing at my friend’s name, Maria (瑪莉亞). At the time, I could not understand why they were mocking the name of Jesus’ mother. Later, I learned that “Maria” had become a stereotype — a shorthand for Filipino migrant workers. That was because many Filipino women in Taiwan, especially those who became house helpers, happen to have that name. With the rapidly increasing number of foreigners coming to Taiwan to work or study, more Taiwanese are interacting, socializing and forming relationships with

Whether in terms of market commonality or resource similarity, South Korea’s Samsung Electronics Co is the biggest competitor of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC). The two companies have agreed to set up factories in the US and are also recipients of subsidies from the US CHIPS and Science Act, which was signed into law by former US president Joe Biden. However, changes in the market competitiveness of the two companies clearly reveal the context behind TSMC’s investments in the US. As US semiconductor giant Intel Corp has faced continuous delays developing its advanced processes, the world’s two major wafer foundries, TSMC and

Earlier signs suggest that US President Donald Trump’s policy on Taiwan is set to move in a more resolute direction, as his administration begins to take a tougher approach toward America’s main challenger at the global level, China. Despite its deepening economic woes, China continues to flex its muscles, including conducting provocative military drills off Taiwan, Australia and Vietnam recently. A recent Trump-signed memorandum on America’s investment policy was more about the China threat than about anything else. Singling out the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as a foreign adversary directing investments in American companies to obtain cutting-edge technologies, it said

The recent termination of Tibetan-language broadcasts by Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA) is a significant setback for Tibetans both in Tibet and across the global diaspora. The broadcasts have long served as a vital lifeline, providing uncensored news, cultural preservation and a sense of connection for a community often isolated by geopolitical realities. For Tibetans living under Chinese rule, access to independent information is severely restricted. The Chinese government tightly controls media and censors content that challenges its narrative. VOA and RFA broadcasts have been among the few sources of uncensored news available to Tibetans, offering insights