Germany’s role as the motor of the European economy is at risk. Growth has been anemic since 2019, as the country grapples with profound structural challenges: an aging population, a tight labor market, declining productivity growth and unprecedented levels of policy uncertainty.

Compounding those challenges, public investment in education and infrastructure has been inadequate even to maintain the existing capital stock. The German Council of Economic Experts (GCEE) projects that potential output growth would average just 0.3 percent annually for the rest of the decade — one-quarter of the average rate during the 2010s. Ahead of Germany’s snap election on Sunday next week, polls show that the economy is at the top of voters’ concerns.

While external and domestic shifts have contributed to Germany’s current malaise, the most important factor can be found in long-term trends weighing on its economy. Without bold, coordinated action from public and private sectors, Germany could face prolonged economic stagnation and a steady decline in competitiveness, once again becoming, as The Economist dubbed it a quarter century ago, “the sick man of Europe.”

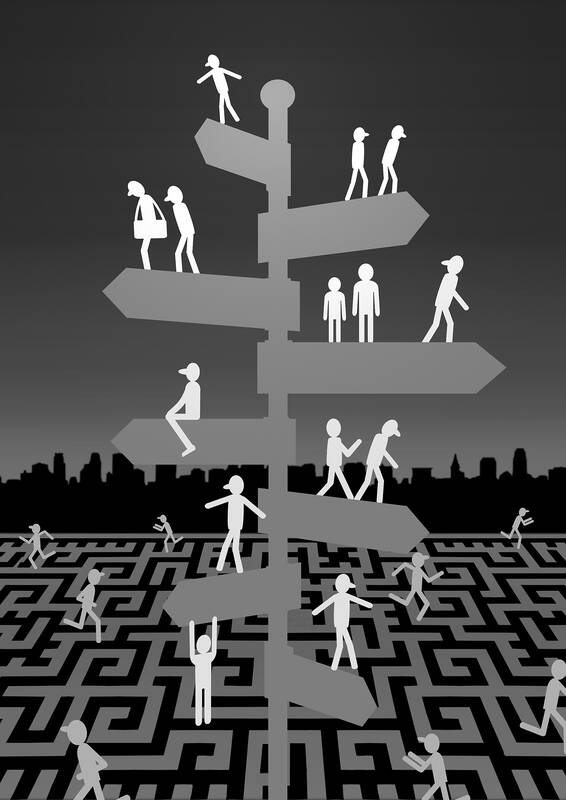

Illustration: Yusha

How did economic conditions in Germany become so grim? Throughout the 2010s, the German economy was a beacon of stability and growth. Its strong industrial base and competitive exports provided a solid foundation of economic resilience, enabling the country to recover rapidly even from the COVID-19 pandemic shock.

So, what changed? At the root of Germany’s economic challenges is its heavy reliance on the manufacturing sector. Although manufacturing’s role has diminished worldwide over the past few decades, with many advanced economies shifting to service and technology-driven growth, Germany has been slow to adapt to those shifts. As a result, Germany’s manufacturing sector, once a pillar of economic strength, has turned into a liability as rising geopolitical tensions, shifting trade patterns and fragile supply chains have made the country’s export-driven growth model increasingly unsustainable.

Germany’s reluctance to overhaul an economic model that performed exceptionally well for so long is understandable. For much of the previous decade, manufacturing was the primary driver of growth, as mid-tech industries benefited enormously from globalization and rising import demand from emerging economies such as China. However, German firms now face intensifying competition in markets they once dominated. Meanwhile, Germany’s slowness to develop high-tech and service-oriented sectors has left it trailing its peers, and its standing in other knowledge-intensive industries has also suffered.

IMPEDIMENTS TO GROWTH

A more recent cause for concern is heightened policy uncertainty, exacerbated by indecisiveness. Delayed reforms and unclear strategies have caused confusion among businesses and financial players, likely dampening private investment and impeding the Germany’s ability to adapt to new economic realities. A survey by the German Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DIHK) showed that policy uncertainty ranks among business leaders’ top concerns, alongside labor costs, energy and raw material prices.

The rising concerns of German business leaders over labor costs and worker shortages are understandable. Labor costs in Germany are among the world’s highest, driven largely by persistent shortages, which undermine the country’s ability to compete in labor-intensive and price-sensitive sectors. Sluggish productivity growth and rising wages have further driven up labor costs. Consequently, Germany’s unit labor costs have deteriorated relative to other major European economies such as France and Spain, eroding its competitive edge.

What is frustrating about those developments is that they were largely predictable, given demographic trends. The country’s labor shortage, driven by a rapidly aging population, has been well-known for decades, but little has been done to mitigate its impact.

To make matters worse, population aging is expected to accelerate over the next 15 years as more German baby boomers reach retirement age. Projections suggest that the old-age dependency ratio — the proportion of people aged 65 or older to the working-age population (aged 20 to 64) — would nearly double between 2000 and 2035. In 2022, Germany had about three working-age people for every person aged 65 or older. By 2040, that figure is expected to drop to just two, as consistently low birthrates and rising life expectancy reshape the country’s demographic profile.

Older workers have significantly lower labor force participation rates and work fewer hours, further shrinking the available workforce. Germany trails behind even countries with a similar demographic structure, especially among workers older than 50. Among individuals aged 50 to 74, Germany’s labor force participation rate is 56.7 percent, compared with 58 percent in Norway, 59 percent in Sweden, and well higher than 60 percent in Japan and New Zealand. The disparity is largely due to Germany’s public pension system, which enables some citizens to retire at 63 years old, creating strong incentives to leave the workforce early. Economic stagnation exacerbates the problem, because firms facing financial pressures often respond by laying off older workers.

As the DIHK survey suggests, the high cost of energy and raw materials is another major barrier to doing business in Germany. Energy prices — particularly electricity and gas — are among the highest in Europe and significantly higher than in other regions, posing a serious challenge to energy-intensive industries such as chemicals and steel.

Although energy prices have eased since reaching record highs in 2022, electricity and natural-gas prices for industrial customers in Germany remain above the European and global averages. In the first half of last year, energy-intensive German firms paid approximately 0.25 euros (US$0.26) per kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity — well above the EU average of 0.22 euros per kWh.

Natural-gas prices have followed a similar trajectory, as liquefied natural gas imports at global market prices have replaced cheaper Russian supplies. Rising costs have eroded the price competitiveness of German products, incentivizing companies to move production to more affordable regions.

In addition to hurting existing industries, high energy prices also hinder the development of emerging sectors. For example, demand for data centers is expected to surge as artificial intelligence (AI) technologies rapidly evolve. However, as long as electricity prices in Germany remain above the EU average, AI companies and others would continue to seek more cost-effective solutions elsewhere.

OPPORTUNIES FOR REVITALIZATION

How can Germany escape its current predicament? An obvious starting point is to close its productivity gap with the US. That gap is not a recent development: over the past 20 years, US productivity growth has outpaced Germany’s by an average of 1 percentage point per year.

The productivity gap has widened in recent years, as the US has made great strides in areas such as AI, digital infrastructure and high-value services. Last year, only 20 percent of German firms used AI. Small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs, or the fabled Mittelstand) — long regarded as the backbone of the German economy — are falling even further behind, owing to financial and technical barriers.

While government initiatives such as the German Agency for Innovation in Cybersecurity have sought to accelerate the country’s technological transformation, the country still lags behind the EU average in most of the Digital Economy and Society Index’s digital infrastructure indicators. Broadband coverage remains limited, especially in rural areas, and investment in digitalization and training is insufficient.

Closing that gap represents a significant opportunity for Germany, as AI and digital infrastructure could help boost productivity and restore competitiveness. To promote future growth, German firms and policymakers must shift their focus from traditional industries such as chemicals and auto manufacturing to emerging sectors such as biosciences. Beyond expanding broadband access, targeted support — particularly for SMEs — would be crucial to facilitate the adoption of AI and other advanced technologies.

The digitalization of public services should be a top priority as well. Establishing standardized government platforms, such as a unified business registration system across Germany’s 16 Lander, or federal states, could streamline bureaucratic processes, benefiting households and companies while strengthening investment incentives. That also applies to digitizing applications and planning procedures for renewable energy projects. Without those measures, Germany risks losing ground in the global race for technological and economic leadership.

Ultimately, technological innovation and economic growth tend to be driven by younger companies. And that underscores a fundamental German shortcoming: While the country has significantly improved its start-up ecosystem and is effective at nurturing companies in their infancy, it struggles to retain them as they scale.

To evolve into globally competitive companies, start-ups require substantial financial resources, access to international markets and a supportive business environment. While early-stage financing has increased since 2007, later-stage funding remains a major hurdle. Only 4 percent of German start-ups successfully scale up, compared with 9 percent in the US. In 2022, the average deal size in Europe was about 8 million euros, whereas in the US, it was nearly 14 million euros, and, as of 2019, more than 40 percent of European companies’ financing rounds included at least one foreign investor. While capital inflows are vital — particularly for later-stage funding — overreliance on foreign venture capitalists increases the risk that companies would keep profits abroad or relocate to other markets, taking their innovations, jobs and economic potential with them.

EUROPEAN INTEGRATION BENEFITS

To ensure that start-ups can scale without relying on foreign investors, Germany needs to foster a domestic venture capital market for growth-stage funding, create incentives for private investment and implement targeted policies aimed at retaining high-potential start-ups. Failing to act risks losing those businesses and undermining Germany’s position as an innovation hub in an increasingly competitive global market.

Building an EU-wide venture capital market is equally critical, requiring concerted efforts at the national and European levels, particularly when it comes to later-stage financing. The process should involve mobilizing resources through institutions such as the European Investment Fund and the European Tech Champions Initiative. While public investment can help bolster later-stage financing, it should facilitate greater flexibility and better risk management by focusing on indirect investments through venture capital funds. That would ensure that investments are guided by the expertise and market knowledge of experienced fund managers.

Collaboration between Germany and other EU member states is essential. The fragmentation of European capital markets restricts investment flows and constrains governments’ ability to support start-ups and scale-ups. A major obstacle is the inconsistency in national insolvency regimes, which makes it difficult to assess the liquidation values of cross-border investments. Those disparities lead to significant variations in recovery rates, deterring investors. Improving and harmonizing national insolvency regimes across Europe would reduce costs, channel more resources to innovative and efficient companies, promote cross-border investment and strengthen financial stability.

However, increased European integration offers significant benefits for the German economy beyond capital inflows. Access to a single market of more than 500 million consumers enables German businesses to expand without facing trade barriers — an enormous competitive advantage for an export-driven economy and for emerging companies deciding whether to scale in the US or the EU.

Moreover, greater European integration would enable industries — even traditional sectors such as auto manufacturing, machinery and chemicals — to achieve economies of scale, reduce costs and boost competitiveness. Seamless cross-border trade would also reinforce Germany’s highly integrated supply chains, enhancing manufacturing efficiency and addressing regulatory inconsistencies that impede cross-border operations. If there was ever a time to pursue full economic integration of the single market, it is now.

INVEST IN LONG-TERM GROWTH

As Germany opens its economy to future-oriented investments, it must commit to public spending that enhances long-term growth. Too often, policymakers have neglected projects whose returns would materialize only after the next election cycle, with lasting economic consequences.

Germany’s chronic underinvestment in education and infrastructure is a prime example. Public spending on education is at 4.5 percent of GDP, below the European average of 4.8 percent. The country’s latest scores from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Program for International Student Assessment and Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies highlight deficiencies in core skills, including literacy, numeracy and problem-solving. Such shortcomings undermine the workforce’s ability to adapt to the demands of a rapidly changing global economy.

Similarly, Germany’s outdated transport, energy and digital infrastructures hamper connectivity and slow productivity growth. Nearly half of the bridges on federal roads are in “adequate” condition or worse, while the rail network requires extensive upgrades. As a result, Germany’s roads are congested and its railways are unreliable, disrupting freight transport and economic activity.

To advance stable, future-oriented spending, policymakers must take three key steps.

First, they should implement systematic cost-benefit analyses to streamline public planning processes.

Second, Germany must reform its debt brake, which limits deficit spending to 0.35 percent of GDP. While intended to enforce fiscal discipline, its inflexibility risks stifling investment. A pragmatic reform could enhance fiscal flexibility without jeopardizing long-term debt reduction. That should include a transition phase following periods when the debt brake is lifted for emergencies, such as natural disasters and other crises beyond the government’s control. A gradual phaseout of the debt brake could help ensure that short-term relief does not come at the expense of long-term stability and might mitigate the effects of external economic shocks.

Furthermore, the structural deficit limit should be adjusted based on the debt-to-GDP ratio. When the debt ratio is below 90 percent, the deficit limit could be increased to 0.5 percent of GDP. If the ratio falls below 60 percent, the limit could be raised to 1 percent. The current 0.35 percent brake would still apply if the debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 90 percent. GCEE simulations showed that such an approach would keep Germany’s debt ratio on a downward trajectory.

Lastly, and perhaps most critically, Germany needs new institutional arrangements to ensure that public funds are directed toward spending on education and infrastructure. One solution is a statutory mandate that sets a minimum investment level in education — such as a per-student spending benchmark — to guarantee stable and sufficient funding. Given that local governments shoulder most education-related expenditures, such a measure would have to be implemented at the state level.

When it comes to transportation infrastructure, a permanent investment fund could stabilize spending on roads and rail networks by securing dedicated revenue sources. Switzerland’s experience showed that reliable funding streams, such as truck and passenger vehicle tolls, could provide long-term financial support for infrastructure maintenance and modernization.

Redirecting revenue from energy and motor vehicle taxes into the transportation fund could provide a stable financial foundation. If limited to federal transportation projects, the German Federal Ministry for Digital and Transport could oversee it, keeping administrative costs low by incorporating the fund into existing structures instead of creating a separate legal entity. To align expenditures with broader government goals, the fund should adopt an intermodal approach, coordinating strategic investments in road, rail and water transport.

To be sure, Germany’s outlook is far from hopeless. There are ample opportunities for the country to restore its growth momentum. However, it must meet the demands of the 21st century by diversifying its economy and developing new growth engines, responding decisively to adverse demographic trends, and closing the investment gap plaguing Germany’s education system and infrastructure. Clinging to what worked in the past is a surefire recipe for continued economic stagnation.

Christian Ochsner and Milena Schwarz contributed to this commentary. Ulrike Malmendier, a member of the German Council of Economic Experts, is professor of finance and economics at the University of California, Berkeley. Thilo Kroeger, senior economist at the German Council of Economic Experts, is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Copenhagen. Christopher Zuber is senior economist at the German Council of Economic Experts.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

US President Donald Trump has gotten off to a head-spinning start in his foreign policy. He has pressured Denmark to cede Greenland to the United States, threatened to take over the Panama Canal, urged Canada to become the 51st US state, unilaterally renamed the Gulf of Mexico to “the Gulf of America” and announced plans for the United States to annex and administer Gaza. He has imposed and then suspended 25 percent tariffs on Canada and Mexico for their roles in the flow of fentanyl into the United States, while at the same time increasing tariffs on China by 10

As an American living in Taiwan, I have to confess how impressed I have been over the years by the Chinese Communist Party’s wholehearted embrace of high-speed rail and electric vehicles, and this at a time when my own democratic country has chosen a leader openly committed to doing everything in his power to put obstacles in the way of sustainable energy across the board — and democracy to boot. It really does make me wonder: “Are those of us right who hold that democracy is the right way to go?” Has Taiwan made the wrong choice? Many in China obviously

US President Donald Trump last week announced plans to impose reciprocal tariffs on eight countries. As Taiwan, a key hub for semiconductor manufacturing, is among them, the policy would significantly affect the country. In response, Minister of Economic Affairs J.W. Kuo (郭智輝) dispatched two officials to the US for negotiations, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC) board of directors convened its first-ever meeting in the US. Those developments highlight how the US’ unstable trade policies are posing a growing threat to Taiwan. Can the US truly gain an advantage in chip manufacturing by reversing trade liberalization? Is it realistic to

Last week, 24 Republican representatives in the US Congress proposed a resolution calling for US President Donald Trump’s administration to abandon the US’ “one China” policy, calling it outdated, counterproductive and not reflective of reality, and to restore official diplomatic relations with Taiwan, enter bilateral free-trade agreement negotiations and support its entry into international organizations. That is an exciting and inspiring development. To help the US government and other nations further understand that Taiwan is not a part of China, that those “one China” policies are contrary to the fact that the two countries across the Taiwan Strait are independent and