After the release of DeepSeek-R1 on Jan. 20 triggered a massive drop in chipmaker Nvidia’s share price and sharp declines in various other tech companies’ valuations, some declared this a “Sputnik moment” in the Sino-US race for supremacy in artificial intelligence (AI).

While the US’ AI industry arguably needed shaking up, the episode raises some difficult questions.

The US tech industry’s investments in AI have been massive, with Goldman Sachs estimating that “mega tech firms, corporations and utilities are set to spend around US$1 trillion on capital expenditures in the coming years to support AI.” Yet for a long time, many observers, including me, have questioned the direction of AI investment and development in the US.

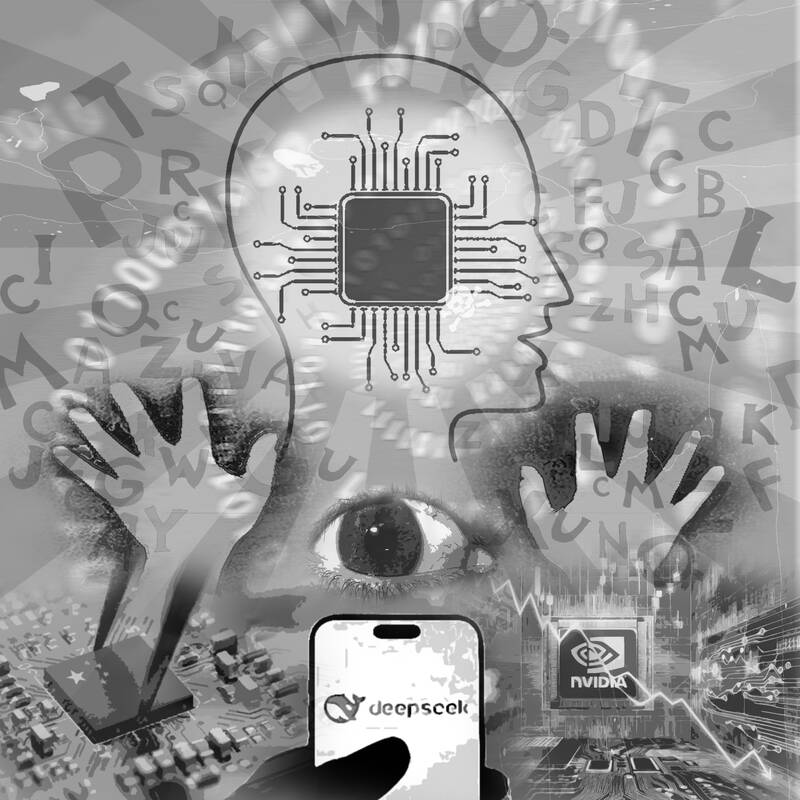

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

With all the leading companies following essentially the same playbook (although Meta has differentiated itself slightly with a partly open-source model), the industry seems to have put all its eggs in the same basket. Without exception, US tech companies are obsessed with scale.

Citing yet-to-be-proven “scaling laws,” they assume that feeding ever more data and computing power into their models is the key to unlocking ever-greater capabilities. Some even assert that “scale is all you need.”

Before Jan. 20, US companies were unwilling to consider alternatives to foundation models pretrained on massive data sets to predict the next word in a sequence. Given their priorities, they focused almost exclusively on diffusion models and chatbots aimed at performing human (or human-like) tasks.

Although DeepSeek’s approach is broadly the same, it appears to have relied more heavily on reinforcement learning, mixture-of-experts methods (using many smaller, more efficient models), distillation and refined chain-of-thought reasoning. This strategy reportedly allowed it to produce a competitive model at a fraction of the cost.

Although there is some dispute about whether DeepSeek has told us the whole story, this episode has exposed “groupthink” within the US AI industry. Its blindness to alternative, cheaper and more promising approaches, combined with hype, is precisely what Simon Johnson and I predicted in Power and Progress, which we wrote just before the generative-AI era began.

The question now is whether the US industry has other, even more dangerous blind spots. For example, are the leading US tech companies missing an opportunity to take their models in a more “pro-human direction”? I suspect that the answer is yes, but only time would tell.

Then there is the question of whether China is leapfrogging the US. If so, does this mean that authoritarian, top-down structures (what James A. Robinson and I have called “extractive institutions”) can match or even outperform bottom-up arrangements in driving innovation?

My bias is to think that top-down control hampers innovation, as Robinson and I argued in Why Nations Fail. While DeepSeek’s success appears to challenge this claim, it is far from conclusive proof that innovation under extractive institutions can be as powerful or as durable as under inclusive institutions.

After all, DeepSeek is building on years of advances in the US (and some in Europe).

All its basic methods were pioneered in the US. Mixture-of-experts models and reinforcement learning were developed in academic research institutions decades ago; and it was US Big Tech firms that introduced transformer models, chain-of-thought reasoning and distillation.

What DeepSeek has done is demonstrate success in engineering: combining the same methods more effectively than US companies did. It remains to be seen whether Chinese firms and research institutions can take the next step of coming up with game-changing techniques, products and approaches of their own.

Moreover, DeepSeek seems to be unlike most other Chinese AI firms, which generally produce technologies for the government or with government funding. If the company (which was spun out of a hedge fund) was operating under the radar, would its creativity and dynamism continue now that it is under the spotlight?

Whatever happens, one company’s achievement cannot be taken as conclusive evidence that China can beat more open societies at innovation.

Another question concerns geopolitics. Does the DeepSeek saga mean that US export controls and other measures to hold back Chinese AI research failed? The answer here is also unclear. While DeepSeek trained its latest models (V3 and R1) on older, less powerful chips, it might still need the most powerful chips to achieve further advances and to scale up.

Nonetheless, it is clear that the US’ zero-sum approach was unworkable and ill-advised. Such a strategy makes sense only if you believe that we are heading toward artificial general intelligence (AGI, models that can match humans on any cognitive task) and that whoever gets to AGI first would have a huge geopolitical advantage. By clinging to these assumptions — neither of which is necessarily warranted — we have prevented fruitful collaboration with China in many areas.

For example, if one country produces models that increase human productivity or help us regulate energy better, such innovation would be beneficial to both countries, especially if it is widely used.

Like its American cousins, DeepSeek aspires to develop AGI, and creating a model that is significantly cheaper to train could be a game changer, but bringing down development costs with known methods would not miraculously get us to AGI in the next few years.

Whether near-term AGI is achievable remains an open question (and whether it is desirable is even more debatable).

Even if we do not yet know all the details about how DeepSeek developed its models or what its apparent achievement means for the future of the AI industry, one thing seems clear: a Chinese upstart has punctured the tech industry’s obsession with scale and might have even shaken it out of its complacency.

Daron Acemoglu, a 2024 Nobel laureate in economics and institute professor of economics at MIT, is a co-author (with Simon Johnson) of Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity (PublicAffairs, 2023).

Copyright: Project Syndicate

The Chinese government on March 29 sent shock waves through the Tibetan Buddhist community by announcing the untimely death of one of its most revered spiritual figures, Hungkar Dorje Rinpoche. His sudden passing in Vietnam raised widespread suspicion and concern among his followers, who demanded an investigation. International human rights organization Human Rights Watch joined their call and urged a thorough investigation into his death, highlighting the potential involvement of the Chinese government. At just 56 years old, Rinpoche was influential not only as a spiritual leader, but also for his steadfast efforts to preserve and promote Tibetan identity and cultural

The gutting of Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA) by US President Donald Trump’s administration poses a serious threat to the global voice of freedom, particularly for those living under authoritarian regimes such as China. The US — hailed as the model of liberal democracy — has the moral responsibility to uphold the values it champions. In undermining these institutions, the US risks diminishing its “soft power,” a pivotal pillar of its global influence. VOA Tibetan and RFA Tibetan played an enormous role in promoting the strong image of the US in and outside Tibet. On VOA Tibetan,

Former minister of culture Lung Ying-tai (龍應台) has long wielded influence through the power of words. Her articles once served as a moral compass for a society in transition. However, as her April 1 guest article in the New York Times, “The Clock Is Ticking for Taiwan,” makes all too clear, even celebrated prose can mislead when romanticism clouds political judgement. Lung crafts a narrative that is less an analysis of Taiwan’s geopolitical reality than an exercise in wistful nostalgia. As political scientists and international relations academics, we believe it is crucial to correct the misconceptions embedded in her article,

Sung Chien-liang (宋建樑), the leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) efforts to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Legislator Lee Kun-cheng (李坤城), caused a national outrage and drew diplomatic condemnation on Tuesday after he arrived at the New Taipei City District Prosecutors’ Office dressed in a Nazi uniform. Sung performed a Nazi salute and carried a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf as he arrived to be questioned over allegations of signature forgery in the recall petition. The KMT’s response to the incident has shown a striking lack of contrition and decency. Rather than apologizing and distancing itself from Sung’s actions,