Riding high in the polls, the anti-immigration Alternative for Germany party (AfD) is in a buoyant mood ahead of German elections on Feb. 23. With all other parties forming a “firewall” against it, the AfD is unlikely to get into power this time, but the next election might be a different matter.

Currently in second place behind the center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Christian Social Union of Bavaria (CSU), the AfD is as close to power as ever before. This has prompted some AfD leaders to promote a softer course, perhaps in the hope of persuading other parties to consider it a viable coalition partner. However, the moderates have lost the argument as the party doubled down on its most radical positions.

For weeks, AfD leader Alice Weidel presented her party as “libertarian-conservative” rather than far right. Her team had even taken the controversial term “remigration” out of the election manifesto since it is used by extremists like the Austrian Martin Sellner, who has advocated the deportations of millions of foreign-born people from Germany, saying even those with residency status or citizenship “might possibly be viable for the remigration policy.”

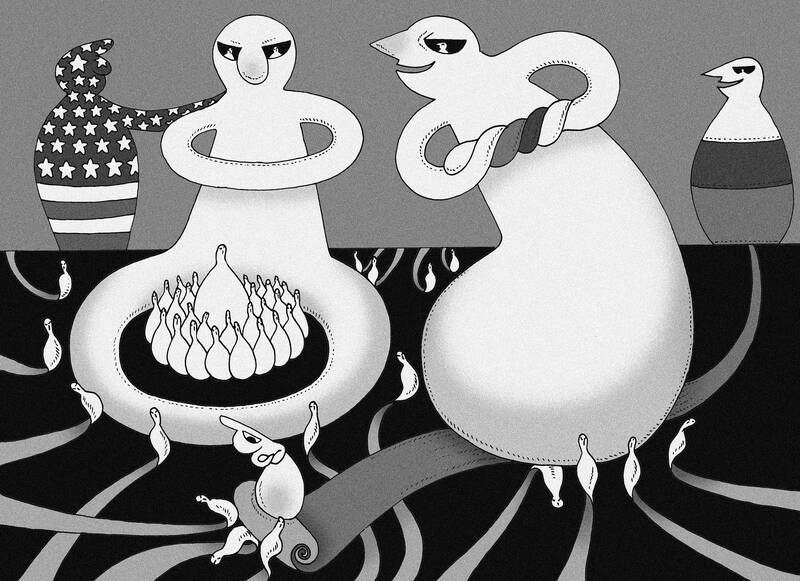

Illustration: Mountain People

Sensing resistance from the powerful radical faction, Weidel changed course. In her fiery speech at the AfD conference this month, she advocated “large-scale repatriations” of immigrants and added: “If it’s going to be called remigration, then that’s what it’s going to be: remigration.”

The term went back into the party program.

Despite the sharpening of the party’s profile, opinion polls predict a vote share of 20 percent and more for the AfD. That is twice the result it achieved at the last election in 2021, but still a long way off from a majority. As is typical in Germany’s electoral system, the AfD would need a coalition partner to be in government. All other parties have vowed to uphold their firewall.

Saskia Esken, leader of Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s center-left Social Democratic Party (SPD), recently questioned on national television whether the conservatives would uphold their firewall “for all eternity.” She is skeptical because there is substantial overlap between the AfD and the conservative CDU/CSU, which is currently predicted to win with around 30 percent. A right-wing coalition with the AfD would create a majority that could tighten immigration policy, lower taxes and loosen economic regulation — things both parties want.

In practice, the CDU/CSU sees many of its core principles violated by the AfD. Founded after World War II, the conservative alliance dominated West German politics for decades. It provided the first postwar chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, who is regarded by many as the founding father of the prosperous, peaceful and democratic Germany that grew out of the ashes of Nazism and war.

Christian-conservative politics was as far right as Germany dared to go after the trauma and guilt associated with the dictatorship, war and genocide. Franz Josef Straus, a prominent conservative of the postwar era, confirmed in 1987 that “there must not be a democratically legitimate party to the right of the CDU/CSU.” The party views itself as the line in modern Germany’s political sand.

Reiner Haseloff, CDU leader of the state of Saxony-Anhalt, recently called this the “foundation myth” of his party, “ruling out” a coalition with the AfD within his lifetime. His party colleague, CDU chair Friedrich Merz, the man most likely to become Germany’s next chancellor, has also argued that a collaboration with the AfD “would kill the CDU.”

There are structural policy differences, too. Adenauer set up the conservative party with an intrinsically transatlantic outlook. This was called “Westbindung,” a binding of Germany to the West, and remains a core principle of CDU/CSU politics today. The AfD, on the other hand, has a strong anti-US streak and wants to tie the country closer to Russia. The manifesto demands “undisturbed trade” with Moscow, the “immediate lifting of economic sanctions” and the “restoration of the Nord Stream pipelines.”

Collaboration with the AfD would go right to the heart of the CDU/CSU, even if some internal party disagreement about this occasionally bubbles to the surface. For now, the AfD must assume that it stands little chance of being approached for a coalition by the likely election winner. So it has not only doubled down on its program, but also on its hostility toward the CDU/CSU. Calling the conservatives a “sham party,” Weidel accused Merz of copying AfD ideas such as border controls to reduce immigration.

The AfD also argues that with the firewall in place, the conservatives have no choice but to form a coalition with parties further to the left, most likely Scholz’s SDP or the Green Party — both part of the defunct ruling coalition. The CDU/CSU was “devoid of any desire for real change,” the AfD claims on the front page of its Web site.

The message that the AfD is the only party for real change is powerful. The firewall forces all other parties into ever greater compromises in order to form coalitions that keep the AfD out. In a recent public conversation with Elon Musk, Weidel claimed they amounted to a “uniparty” giving voters variations on a theme, regardless of how they vote.

The exclusion of the AfD from compromise politics has allowed the party to keep its program radical and discernibly different, which is appealing in itself to many disgruntled voters. Take the AfD’s core issue of immigration, which is consistently the number one topic for voters in the polls. The CDU/CSU has hardened its stance there, but unlike the AfD, it would have to compromise on that since all other parties sit further to the left on this issue.

Weidel was optimistic when she said: “Let us overtake the CDU.”

The election is only one month away and there is a 10-point gap between the parties, but that gap has shrunk in all polls in the last few weeks.

Should Merz win as predicted and form a coalition with one or even two of the parties that were in the deeply unpopular coalition that has just collapsed, he runs the risk of his brand new government starting off with the message that nothing will change. The AfD would sit in opposition with twice the seats and be entirely unrestrained by compromise dynamics. It would be free to criticize the government’s every move and harness people’s anger.

If the next four years continue to frustrate German voters, the AfD’s strategy to stay the radical outlier might well pay off.

As Berlin Mayor Kai Wegner of the CDU put it recently: Germany’s mainstream parties might “have exactly one shot left.”

Katja Hoyer is a British-German historian and journalist. Her latest book is Beyond the Wall: A History of East Germany. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its