The wildfires terrorizing Los Angeles this week have been like something out of a movie: vast, fast-moving, unpredictable and merciless. Their scope and nature have surprised even fire-jaded California. They are also evidence of the sort of consequences that can be expected as the planet continues to heat, consequences for which traditional risk-management tools — like, say, home insurance — are increasingly obsolete.

The fires did not even exist on Tuesday morning. The only hint of what was to come were forecasts for some of the strongest and most dangerous Santa Ana winds on record to barrel out of the Great Basin and into Southern California. Those hurricane-force blasts can be destructive enough, but these coincided with drought conditions, dry vegetation, low humidity and relatively high air temperatures, leading the US National Weather Service to issue an “extremely critical” fire-weather warning for the area around Los Angeles, the first-ever such warning in the lower 48 US states in January.

It did not take long to see the results. Within hours, a serious fire was threatening the Pacific Palisades neighborhood in western Los Angeles, moving so quickly that some residents abandoned their cars on the road and fled by foot.

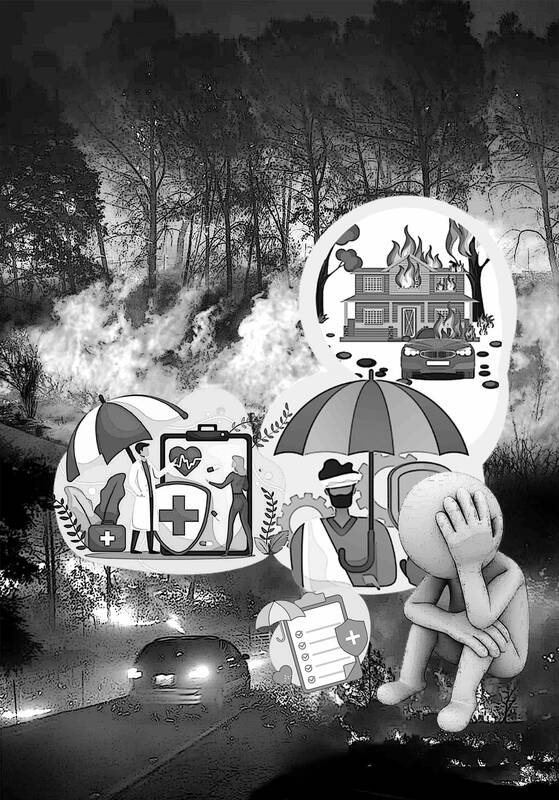

Illustration: Constance Chou

By Wednesday morning, three out-of-control fires had spread across 4,500 acres (1,821 hectares) around the city, taking at least two lives and destroying at least 100 buildings and threatening hundreds of thousands of people and tens of thousands of homes and businesses, and the emergency had not yet peaked, with strong winds expected to continue the rest of the week.

There have always been Santa Ana winds and wildfires in California, but climate change, along with human development has made the combination of the two much more destructive. Warmer air drops more moisture when it rains and snows, which encourages plant life in the spring, but then all those plants become kindling during hot, bone-dry summers and falls.

When the Santa Ana winds blow down through the canyons out of the Great Basin in the colder months, all it takes is a spark to create a monster fire that spreads quickly.

Those fires generate new sparks, spreading fires across landscapes that over the past few decades have been filled with houses. These structures, built in what is known as the wildlife-urban interface, become their own kindling, as Tim Sahay, co-director of the Net Zero Industrial Policy Lab, wrote on Bluesky.

The glut of homes in increasingly fire-prone places has created an insurance crisis in California, with many big insurers pulling out of the state to avoid more losses. Nearly 500,000 Californians have turned to the state’s insurer of last resort, the California Fair Access to Insurance Requirements Plan (FAIR), which has doubled in size over the past five years.

The state is now exposed to nearly US$458 billion in potential damage, a figure that has nearly tripled since 2020.

The neighborhoods in the path of the Palisades and other fires burning this week have been among some of the hardest-hit by insurer defections in recent years. The 90272 ZIP code of Pacific Palisades experienced 1,930 policy non-renewals between 2019 and last year, or 28 out of every 100 policies, data compiled by the San Francisco Chronicle showed.

Pacific Palisades is also the state’s fifth-largest user of FAIR policies, with nearly US$6 billion in exposure.

Even a fraction of that amount would exceed the capabilities of FAIR, which at last report had about US$700 million in cash. Additional damage can be passed on to private insurers, which would pass those costs immediately to their less risky customers.

California Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara last month announced policy tweaks to encourage insurers to come back to the state. They can now use catastrophe modeling to set rates after long being required to consider only historic losses.

However, part of their modeling must also include fire-defense measures property owners take. Insurers can also now pass the cost of reinsurance on to their customers. Providers lured back to the state by these incentives must cover risky areas at a rate of 85 percent of their statewide market share.

The aim of such reforms is to boost the availability of private insurance, keep it affordable and improve the adequacy of coverage — the three “A’s,” as Kenneth Klein, professor at California Western School of Law in San Diego, puts it.

He said the new regulations would probably help with availability, but they definitely would not help with affordability; insurers would raise rates, and they would be using black-box models to do so.

Private insurance plans would be more adequate, meaning they would cover more damage, than the FAIR Plan. They are typically “replacement cost value” plans, compared with FAIR’s “actual cash value” plans.

However, even private insurance plans are not always enough to fully reimburse a homeowner, given rising rebuilding costs, especially after a widespread disaster. Klein said 80 percent of Americans do not have enough home insurance.

“People buying from private insurers will think they have full and adequate insurance. Their insurer may even think that,” Klein said. “Most of them will not have that, and they’ll never know it because they’ll never have their home destroyed.”

This is not just a California problem. Other states on the front lines of climate change are underinsured for fires, floods, hurricanes and other disasters that are becoming more frequent or intense or both as Earth warms.

There might be more than US$1 trillion in hidden home-value losses from floods and fires alone, posing the threat of a mini-financial crisis. Florida and many other states have their own insurance crises, which they have managed to varying degrees of failure. Many homeowners in these places are turning not only to state insurers, but lightly regulated insurers, taking on even more risk for themselves and ultimately taxpayers.

At some point, policymakers and the people living in risky places would have to decide when enough is enough. How many times should we pay to rebuild a home on a wildfire-prone California hillside or a flood-prone North Carolina beach? How many first responders’ lives are worth risking so people can have beautiful views? When does insurance become a Band-Aid on a gushing wound?

The first and best thing we can do is stop burning the fossil fuels that are heating the planet and making the problem worse. Until then, homeowners should understand just how much insurance coverage they truly need and react accordingly. It is possible to build fire and flood-resistant structures, but can you afford them?

Policymakers need to decide when to let the rising seas or expanding deserts take over land where people used to be and build new, affordable housing for those people in safer areas. This would involve reorganizing how society thinks about property risk, but if we do not start that process now, it would be forced on us, probably when we least expect it.

Mark Gongloff is a Bloomberg Opinion editor and columnist covering climate change. He previously worked for Fortune.com, the Huffington Post and the Wall Street Journal. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its