When the history of this tumultuous week in South Korean politics is written, legislators who demanded the president rescind his declaration of martial law would surely be lauded. It is also worth standing back to examine the role that economics has played in the country’s transition to democracy and why that least-worst system of government survived.

The contribution of capitalism — its constraints and opportunities — has been vital. The rhythms of global commerce have been present at key points in South Korea’s journey. It is fair to say that without the thrills and spills of money, there would not have been a mature democracy to protect. That you may not have noticed is a testament to its success and durability.

Of all the potential year-end shocks that traders had gamed out, Tuesday night’s brief, but alarming events did not come close to making the cut. Markets were braced for social media posts on outlandish cabinet picks by US president-elect Donald Trump, new tariff threats and the prospect of a French government implosion, not an attempted coup by South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol.

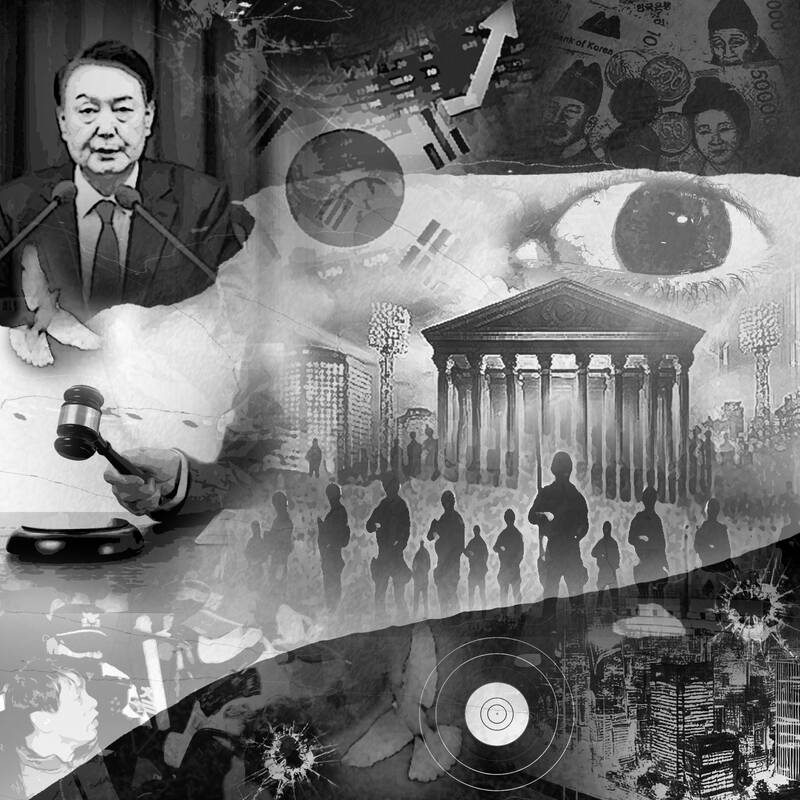

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

The reaction was swift, but contained: The currency tumbled in offshore trading, along with other assets tied to South Korea. By Wednesday morning, after lawmakers rebuked Yoon, the won had recouped losses and bonds were little changed.

Equities fell in local trading, but by no means was it a bloodbath. Regulators were ready to provide ample liquidity. Dramatic gestures such as shutting the stock exchange were eschewed, as were panicky moves such as further interest rate cuts. Officials backstopped the system without fuss.

That is the way it is supposed to work: Instill confidence, not sap it. Textbook central banking.

That does not mean the economy would sail smoothly. GDP rebounded slightly in the third quarter from a modest contraction in the previous three months. The Bank of Korea had already signaled its worries by unexpectedly reducing borrowing costs last week and making concerned noises about a resumption of trade wars. However, a cyclical downdraft is different from a shock that strikes at the heart of the administration. (When I wrote that the country was preparing for bleak days, the would-be putsch was not what I foresaw.)

The good news is that economics and political upheaval have often been strange bedfellows in South Korea — and elsewhere in Asia. As military-backed leaders in Seoul pushed rapid industrialization in the years after the 1950 to 1953 war that left the peninsula divided, it was almost inevitable that prosperity would bring with it a rising middle class that became more aspirational and demanded a greater say in how it was governed. The scrutiny that came with integration in supply chains, inbound and outbound investment, and the price demanded for access to global markets forced South Korea to clean up its act.

Booms also bring busts and Seoul came within an inch of default in the late 1990s during the Asian financial crisis. As wrenching as the meltdown was, it was also part of a big shift in the country’s politics. For the first time, a long-standing opposition politician, Kim Dae-jung, was elected president. Government figures tried to murder him during the dictatorship years, but US intervention kept Kim alive. His moment came and the transition to full democracy was complete.

As lawmakers debated the future of the now disgraced Yoon on Wednesday, former South Korean minister of trade Yeo Han-koo sat down with Bloomberg journalists in Singapore.

I asked him whether, from a historical vantage point, the ebbs and flows of capitalism were effectively the midwife to democracy in Korea.

“Absolutely,” Peterson Institute for International Economics senior fellow Yeo said. “There’s no turning back.”

Financial swings also led to a revolution and, ultimately, a freer system in Indonesia. It has not been perfect; the years after the International Monetary Fund imposed harsh conditions on loans that pushed autocratic, former Indonesian president Suharto out were marred by communal violence and efforts by far flung provinces to break away. Although Suharto’s son-in-law, Prabowo Subianto, now sits in the presidential office, he had to get there the hard way — via the ballot box. In Malaysia, former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad held on to power for a few years after the financial collapse, but the ructions it produced cemented Anwar Ibrahim as the leading alternative. Anwar became premier in 2022 and presides over a sprawling coalition that, against the odds, he has held together.

There are exceptions to these encouraging stories: China did not democratize as its economy flourished and markets took shape. If anything, it has gone in the opposite direction: Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) has accrued more personal authority than any leader since Mao Zedong (毛澤東). Perhaps the moral is you have to be very big to stand against the forces that thriving capitalism and an open economy unleash. Taiwan did manage the transition after decades of enviable growth.

Governance can take detours, as Koreans have found out. However, the necessities of operating within the global economic system also bring checks on the power of ambitious leaders. Let us salute the people of South Korea, but also the not-so-invisible hand of commercial priorities.

Daniel Moss is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian economies. Previously, he was executive editor for economics at Bloomberg News.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its