As his second official spell as Japanese prime minister began on Monday, Shigeru Ishiba was asleep at the wheel.

The Japanese leader drew headlines for a moment after he was caught napping in parliament during proceedings for his own nomination as Japanese leader. It is common for Japanese politicians, who must sit through hours of tedious parliamentary debates that most global peers do not, to catch up on microsleep.

Ishiba’s spokesman blamed cold medicine. However, Ishiba might well wish he had stayed asleep. He already had plenty to worry about. He is still smarting from a resounding election defeat and has just formed a minority government, Japan’s first in three decades, which is sure to be unstable. The head of the party whose help he needs most to pass legislation is in trouble, having just admitted to an extramarital affair. Two of Ishiba’s own Cabinet ministers and the leader of his coalition partner lost their seats in the election rout. That the Liberal Democratic Party did not join the growing list of global incumbents turfed out of power this year might just be due to timing, with Japan’s main opposition party also in the midst of a reorganization.

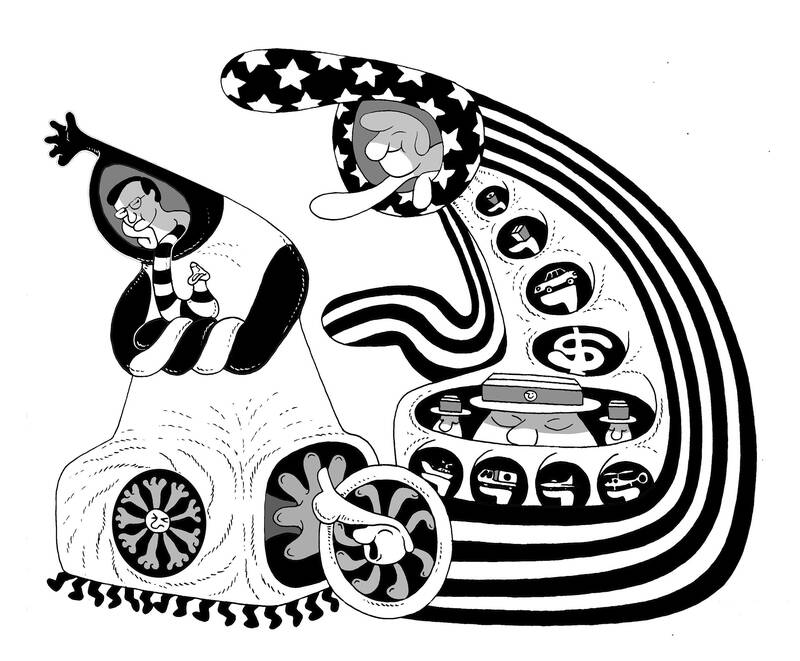

Illustration: Mountain People

The increasingly unpopular premier must deal with the return of former US president Donald Trump, a man who once said the only thing he liked about Japan was that people bow instead of shaking hands.

After three years of record stability in the Japan-US alliance, it injects a new level of chaos into a relationship crucial for regional peace. Ishiba’s phone call with the US president-elect — described by the prime minister as “outstandingly friendly” — was, at just five minutes, much shorter than those held with other world leaders. Now he must arrange a high-stakes meeting with Trump recalling memories of 2016 when Japanese officials hastily cobbled together a visit to Trump Tower by then-Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe, complete with a present of a golden golf club. That gesture kicked off a golf-led “bromance” that protected Japan from Trump’s excesses.

Tokyo is prepared this time, having welcomed several of the president-elect’s inner circle in recent months. Former Japanese prime minister Taro Aso was dispatched to New York in April, with expectations he could be Japan’s “Trump whisperer” in the absence of Abe, who was assassinated in 2022. However, after Aso backed rival former Japanese minister of state for economic security Sanae Takaichi in September’s party leadership race, he was punished with a figurehead position that pushes him to the fringes of the ruling party. Aso’s look of sheer disdain at Ishiba’s parliamentary napping suggests he might be of limited help.

The prime minister could therefore find himself exposed. His political mentor, the 1970s Japanese prime minister Kakuei Tanaka, once said a prime minister needed to have experience heading two of the three big ministries: finance, foreign affairs and what is now the ministry of economy and trade. Ishiba has led none of them.

Personally, would Trump have patience for Ishiba’s circuitous and often grating conversational style? Where Abe was educated in the US and among the circles of power since boyhood, Ishiba has limited international experience. While Abe spent much of his visits on the links, Ishiba reportedly has not golfed since becoming a lawmaker nearly four decades ago. (His South Korean counterpart, President Yoon Suk-yeol, has taken up the sport for the first time in eight years.)

Ishiba on Monday put considerable distance between Trump’s transactional approach to international relations and his, saying he did not think diplomatic relations were “a world of give-and-take deals.” Given the US president-elect seems to have limited appetite for NATO, it seems highly unlikely he would back his Japanese counterpart’s dated plan for an Asian version. While the two men might agree that the current US-Japan alliance is unfair, they are likely to find they differ about which side bears the inequitable burden.

Thanks in large part to Abe’s diplomacy, Japan largely dodged the trade wars of the first administration. However, since then, its trade surplus with the US has only increased, with exports there rising more than 40 percent compared with 2016, overtaking those to China. Officials fret that Trump might also demand Japan increase its defense spending to 3 percent of GDP, even as the country struggles to finance its goal of spending 2 percent.

Yet in these differences, Ishiba might even spy an opportunity. That seemed to be the message of a recent controversial interview with his foreign policy adviser, Takashi Kawakami, in the Daily Cyzo.

While the interview largely made waves in English for Kawakami’s comments on the Jan. 6, 2021, riots at the US Capitol, for watchers of the countries’ alliance, it contained more concerning thoughts. Kawakami suggested that by exploiting Trump’s lack of interest in traditional partnerships, Japan can become a “truly independent country,” rethinking its position not just vis-a-vis the US, but also China, Russia and North Korea. In theory, the idea of a Japan with greater independence is a good one. Yet in the reality that is the current unstable Indo-Pacific region, it is worrying to think of Tokyo using Trump to drift away from Washington. Would a Japan no longer under the US security umbrella need its own nuclear weapons? Could a more non-aligned country be pulled closer into China’s sphere of influence?

It still seems unlikely that Ishiba or his advisers would be around long enough to make a lasting impact on US-Japan relations: He has bought time to prioritize the passing of this year’s extra spending and next year’s regular budget, but after that, all bets are off, especially amid a looming upper house election next summer.

On both sides of the Pacific, everything about politics in the past few months has surprised the experts — including the identity of both of the leaders of one of the world’s most crucial alliances. This is no time to snooze.

Gearoid Reidy is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Japan and the Koreas. He previously led the breaking news team in North Asia and was the Tokyo deputy bureau chief.

Trying to force a partnership between Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) and Intel Corp would be a wildly complex ordeal. Already, the reported request from the Trump administration for TSMC to take a controlling stake in Intel’s US factories is facing valid questions about feasibility from all sides. Washington would likely not support a foreign company operating Intel’s domestic factories, Reuters reported — just look at how that is going over in the steel sector. Meanwhile, many in Taiwan are concerned about the company being forced to transfer its bleeding-edge tech capabilities and give up its strategic advantage. This is especially

US President Donald Trump’s second administration has gotten off to a fast start with a blizzard of initiatives focused on domestic commitments made during his campaign. His tariff-based approach to re-ordering global trade in a manner more favorable to the United States appears to be in its infancy, but the significant scale and scope are undeniable. That said, while China looms largest on the list of national security challenges, to date we have heard little from the administration, bar the 10 percent tariffs directed at China, on specific priorities vis-a-vis China. The Congressional hearings for President Trump’s cabinet have, so far,

US political scientist Francis Fukuyama, during an interview with the UK’s Times Radio, reacted to US President Donald Trump’s overturning of decades of US foreign policy by saying that “the chance for serious instability is very great.” That is something of an understatement. Fukuyama said that Trump’s apparent moves to expand US territory and that he “seems to be actively siding with” authoritarian states is concerning, not just for Europe, but also for Taiwan. He said that “if I were China I would see this as a golden opportunity” to annex Taiwan, and that every European country needs to think

For years, the use of insecure smart home appliances and other Internet-connected devices has resulted in personal data leaks. Many smart devices require users’ location, contact details or access to cameras and microphones to set up, which expose people’s personal information, but are unnecessary to use the product. As a result, data breaches and security incidents continue to emerge worldwide through smartphone apps, smart speakers, TVs, air fryers and robot vacuums. Last week, another major data breach was added to the list: Mars Hydro, a Chinese company that makes Internet of Things (IoT) devices such as LED grow lights and the