The world is feeling the angst of liminality, as the US’ friends and foes await the outcome of the presidential election tomorrow. Would the superpower have former US president Donald Trump or US Vice President Kamala Harris as commander-in-chief? Until that question is answered, nothing much can move; nothing of note can be resolved. However, what if no answer is forthcoming, at least not for a while?

Picture decisionmakers around the world holding their collective breath right now. In the Middle East, which teeters on the edge of major regional war, envoys from Israel, Egypt, the US and Qatar are once again meeting in Doha about a ceasefire in the Gaza Strip. However, nobody would commit to anything until US voters decide who is to sit at the Resolute Desk come January.

In the Kremlin, Russian President Vladimir Putin is waiting for tomorrow’s result to decide his next steps in Ukraine and elsewhere. (He is rooting for Trump, but wary of that scenario, too.) In North Korea, Kim Jong-un is paying close attention to the vote as he brandishes his nukes at South Korea. From Beijing to Tehran, Minsk to Caracas, anti-US autocrats are on tenterhooks to find out who their new adversary would be.

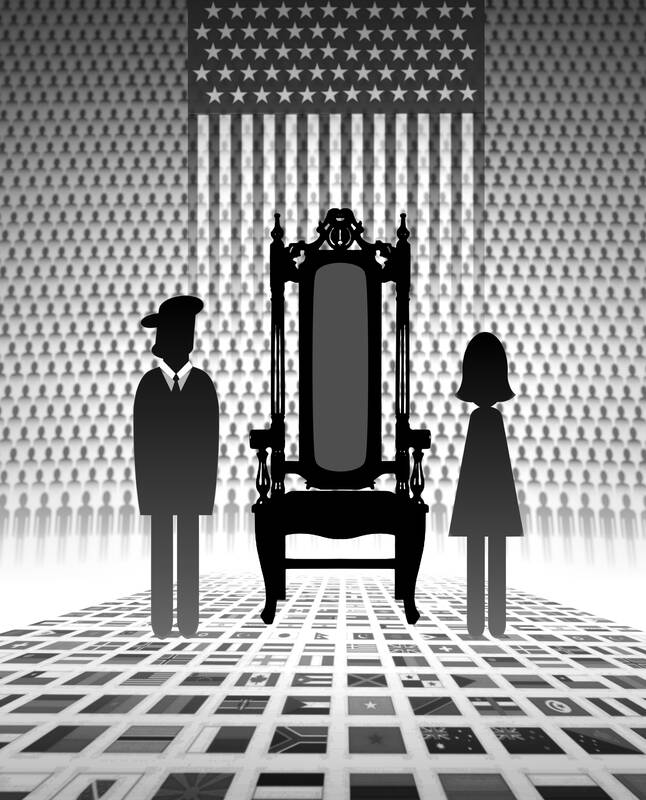

Illustration: Yusha

The US’ allies are in limbo, too. Japan, which was already nervous about a second Trump turn, suddenly has its own government crisis, after an election that left no clear winner for the first time since the 1990s. Germany’s government, a year from the next parliamentary election, is a zombie coalition that might fall apart at any moment. Like all US allies, Tokyo and Berlin wonder if they would still have a friend in the White House next year, or instead a nationalist who slaps tariffs on their exports and threatens to abandon them to their enemies.

Then there are all the other countries, those which are neither allies nor adversaries of the US, but once looked to it, and only it, to provide some semblance of order in an anarchical world. That is true from the South Pacific to Africa, where nations are feeling pressure to decide between the US and China in mapping out future allegiances. The angst is especially acute in places such as Moldova and Georgia, which are swaying between a Russian-dominated East and the Euro-US West, and just had elections in which Moscow, as usual, ran massive disinformation campaigns.

The liminality extends to the multilateral system, as embodied in the UN and other institutions of international law. Already losing relevance in a world of war and disorder, the UN might not survive, at least not in any recognizable form, a second term by Trump, who dismisses the organization as a club of “globalists.” Its fate under Harris is almost as unclear.

Even if Trump wins, tomorrow might bring some relief, as long as it delivers a decision and indicates a clear direction. However, worse scenario cannot be ruled out. That is an absence of resolution, through a contested transfer of power that plays out over months, either in the courts or, heaven forbid, in the streets, with verbal or physical violence of the kind that the US used to criticize in other countries.

Neither the US nor the world has experience with such a horror script set in the US. The close election of 2000 (when George W. Bush defeated Al Gore, but only by a hair and after much lawyering) was a cliffhanger. However, it took place during a “unipolar” moment of geopolitics, when no other power dared to test US might and resolve during the transition.

The contentious handover of 2020 was more dangerous, but found resolution once the coup of Jan. 6, 2021, failed. World politics was already wobbly, but not yet careening: That happened more recently, after Putin invaded all of Ukraine, after Hamas massacred Israelis and Israel bombed Gaza and Lebanon, and as China ratcheted up its intimidation of Taiwan. Worse yet, Russia, China, North Korea and Iran began forming an anti-US “axis” in all but name, raising the specter of World War III.

A contested transition this year would be more perilous for another reason. Domestic polarization and foreign disinformation are old news. This year, Russia, China and Iran have plumbed new depths of malign sophistication in the propaganda and conspiracy theories they plant and spread to pit Americans against one another. Trump is likely to build on his “Big Lie” about the 2020 election with even bigger lies, and the trolls and bots of the US’ enemies, as well as “useful idiots” in the country itself, would amplify them.

Even if the US avoids violence this fall and winter, even if either Trump or Harris arrives uncontested in the Oval Office, even if the White House and Congress go to the same side: This larger “epistemic crisis” would keep the US divided and the world in the lurch. Just as Americans can no longer agree on who won an election, they are increasingly unable to stipulate who is the aggressor or victim in Ukraine, what principles and interests are worth the US’ trouble abroad, and what its proper role in the world should be.

Nature abhors a vacuum, Aristotle said. So does geopolitics. The world risks facing a vacuum in the coming months and years, no matter what the ballot count says next week — a vacuum not so much of power, as of truth, reason and ambition.

Andreas Kluth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering US diplomacy, national security and geopolitics. Previously, he was editor-in-chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for The Economist.

Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention. If it makes headlines, it is because China wants to invade. Yet, those who find their way here by some twist of fate often fall in love. If you ask them why, some cite numbers showing it is one of the freest and safest countries in the world. Others talk about something harder to name: The quiet order of queues, the shared umbrellas for anyone caught in the rain, the way people stand so elderly riders can sit, the

Taiwan’s fall would be “a disaster for American interests,” US President Donald Trump’s nominee for undersecretary of defense for policy Elbridge Colby said at his Senate confirmation hearing on Tuesday last week, as he warned of the “dramatic deterioration of military balance” in the western Pacific. The Republic of China (Taiwan) is indeed facing a unique and acute threat from the Chinese Communist Party’s rising military adventurism, which is why Taiwan has been bolstering its defenses. As US Senator Tom Cotton rightly pointed out in the same hearing, “[although] Taiwan’s defense spending is still inadequate ... [it] has been trending upwards

After the coup in Burma in 2021, the country’s decades-long armed conflict escalated into a full-scale war. On one side was the Burmese army; large, well-equipped, and funded by China, supported with weapons, including airplanes and helicopters from China and Russia. On the other side were the pro-democracy forces, composed of countless small ethnic resistance armies. The military junta cut off electricity, phone and cell service, and the Internet in most of the country, leaving resistance forces isolated from the outside world and making it difficult for the various armies to coordinate with one another. Despite being severely outnumbered and

After the confrontation between US President Donald Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy on Friday last week, John Bolton, Trump’s former national security adviser, discussed this shocking event in an interview. Describing it as a disaster “not only for Ukraine, but also for the US,” Bolton added: “If I were in Taiwan, I would be very worried right now.” Indeed, Taiwanese have been observing — and discussing — this jarring clash as a foreboding signal. Pro-China commentators largely view it as further evidence that the US is an unreliable ally and that Taiwan would be better off integrating more deeply into