China is quietly easing regulatory pressure on private tutoring operators as it looks to revive a flagging economy, spurring a nascent revival of a sector hit hard by a government crackdown three years ago, according to industry figures, analysts and data reviewed by Reuters.

There has been no formal acknowledgement of a change in policy. However, there is now tacit consent from policymakers to allow the tutoring industry to grow, in a pivot by Beijing to support job creation, eight industry figures and two analysts familiar with the developments told Reuters.

The shift is evident in new growth among tutoring businesses and moves by Beijing to clarify its approach, as well as in Reuters interviews with five Chinese parents who described a gradual liberalization in recent months.

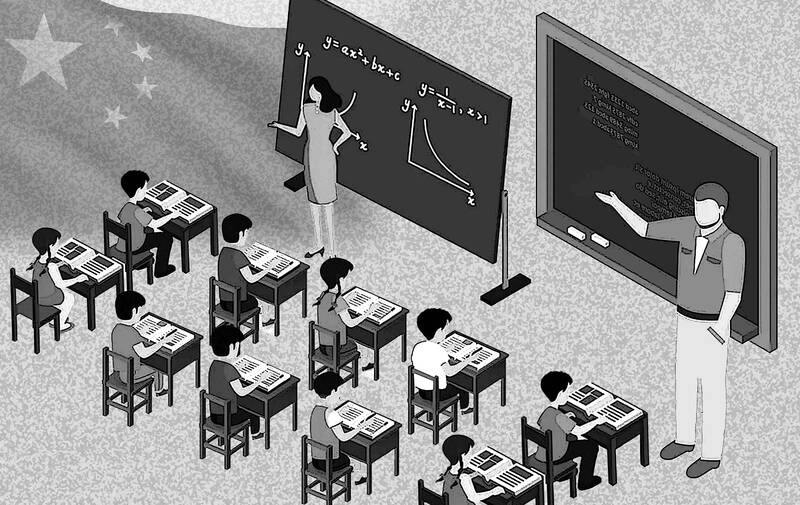

Illustration: Constance Chou

Details in this story about the relaxation of policy enforcement and the increasing openness of tutoring organizations’ operations have not been previously reported. Starting in 2021, a government crackdown known as the “double reduction” policy prohibited for-profit tutoring in core school subjects, with the aim of easing educational and financial pressure on parents and students.

The move wiped billions of US dollars off the market value of providers such as New Oriental Education & Technology Group and TAL Education Group, and led to tens of thousands of job losses. Before the crackdown, China’s for-profit tutoring industry was valued at about US$100 billion and its three biggest players employed more than 170,000 people.

Still, the industry proved resilient, as parents such as Michelle Lee, 36, continued to seek tutoring services to give their children a leg-up in China’s ultracompetitive education system.

Lee, who is based in southern China, spends 3,000 yuan a month, or about US$421, on after-school classes for her son and daughter, including one-on-one mathematics tutoring and online lessons in English.

In recent months, tutoring schools had been operating more openly than they have since 2021, she told Reuters.

“When the policy first came out, I think those tutoring organizations were a little bit scared, so they kind of hid, like they would close the curtains during class,” she said. “But it seems like they don’t do that anymore.”

In China’s high-pressure educational environment, parents have little choice, but to rely on outside tutoring just so their children can keep pace, Lee said, adding that she had “felt a huge sense of failure” as she tried to support her children’s education.

The Chinese Ministry of Education did not respond to questions about its evolving approach to the tutoring industry.

“Pain points” in education policy were gradually being addressed, Liu Xiya (劉西亞), a delegate of China’s legislature and president of a Chongqing-based education group, told local media at a ministry press conference in March.

China was unlikely to admit that the crackdown “was a little too forceful,” ING Greater China chief economist Lynn Song (宋林) said.

Rather, there would be a “tacit easing back toward a looser regulatory stance,” he said.

“The overall policy environment has shifted from restrictive to supportive, as the main goal now is stabilization,” Song said, adding that the tutoring industry should benefit from the broader shift.

Government moves to ease the crackdown had accelerated in recent months, two executives at large tutoring companies who deal with regulatory issues told Reuters.

Most notable was a decision in August by the Chinese State Council, China’s cabinet, to include education services in a 20-point plan to boost consumption — a key aspect of Beijing’s efforts to fire up the economy. The move boosted stocks of listed education companies and came as more than 11 million university graduates entered China’s employment market.

That announcement followed draft guidelines from the Chinese Ministry of Education in February, which clarified the kinds of off-campus tutoring that would be permitted, and its introduction last year of an online “white list” of companies approved to provide tutoring in non-core subjects.

In addition, inspections by local authorities of tutoring schools have lessened considerably of late from their peak early in the crackdown, one of the executives said.

Both executives said the message they have received from Chinese officials since August is that the tutoring industry would remain tightly regulated, but with a wider pathway to operate successfully and above-board, provided operators do not flout restrictions on teaching core academic curriculum. They spoke on the condition of anonymity, because they were not authorized to talk to the media.

Having eliminated some low-quality players, the government was pinning hope on the education sector to help address “super high” youth unemployment, said Claudia Wang (王津婧), who leads the Asia Education Practice at consultancy Oliver Wyman.

“I think that’s very, very fundamental to the shift,” Wang said.

Hiring patterns and other moves by listed education firms point to an expansion of the industry this year.

Active licenses for extracurricular for-profit tutoring centers rose by 11.4 percent between January and June, research firm Plenum China said.

TAL and New Oriental have been hiring for thousands of positions this year, according to data from their annual reports and a Reuters review of job listings on major Chinese employment platforms.

The number of schools and learning centers operated by the two groups has also rebounded, data from the companies and Plenum China showed.

The companies’ shares have traded this year at their highest on average since 2021, although still far below pre-crackdown levels.

New Oriental declined to comment to Reuters about how it was responding to the changing regulatory landscape, while TAL did not reply to a similar request.

In its annual report in September, New Oriental noted continuing “significant risks” from the ways in which regulations and policies related to private education are interpreted and implemented.

“We have been closely monitoring the evolving regulatory environment and are making efforts to seek guidance from and cooperate with the government authorities to comply,” the report said.

Another reason for the industry’s revival is that it proved impossible to eliminate. In practice, private tutoring operators, while diminished, continued to exist in various forms, often redesigning courses to skirt restrictions or advertising them under code words. Mathematics-related courses, for example, are commonly marketed as “logical thinking.”

Lisa, who declined to give her full name for fear of official retribution, runs an English tutoring school in the eastern province of Zhejiang. It shifted its curriculum to comply with rules that prohibit the teaching of core subjects such as mathematics and English.

Lisa said she laid off 60 percent of her staff following the crackdown. However, the school maintained classes by pivoting to teaching science-related courses in English, without calling them English classes.

Meanwhile, one-on-one tutoring flourished, as parents who could afford the higher prices hired tutors to come to their homes.

That worried parents such as Yang Zengdong, a Shanghai-based mother of two, who said the policy presented families with the unenviable choice of paying up to 800 yuan per class for a private tutor or investing hours each day themselves in helping their children keep up.

“If double reduction continues, the academic gap between rich people and everyone else will get worse,” she said. “That wasn’t what the policy was meant to do, but that’s the reality, so of course it needs to change.”

Additional reporting by Ellen Zhang and the Shanghai newsroom

Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention. If it makes headlines, it is because China wants to invade. Yet, those who find their way here by some twist of fate often fall in love. If you ask them why, some cite numbers showing it is one of the freest and safest countries in the world. Others talk about something harder to name: The quiet order of queues, the shared umbrellas for anyone caught in the rain, the way people stand so elderly riders can sit, the

Taiwan’s fall would be “a disaster for American interests,” US President Donald Trump’s nominee for undersecretary of defense for policy Elbridge Colby said at his Senate confirmation hearing on Tuesday last week, as he warned of the “dramatic deterioration of military balance” in the western Pacific. The Republic of China (Taiwan) is indeed facing a unique and acute threat from the Chinese Communist Party’s rising military adventurism, which is why Taiwan has been bolstering its defenses. As US Senator Tom Cotton rightly pointed out in the same hearing, “[although] Taiwan’s defense spending is still inadequate ... [it] has been trending upwards

After the coup in Burma in 2021, the country’s decades-long armed conflict escalated into a full-scale war. On one side was the Burmese army; large, well-equipped, and funded by China, supported with weapons, including airplanes and helicopters from China and Russia. On the other side were the pro-democracy forces, composed of countless small ethnic resistance armies. The military junta cut off electricity, phone and cell service, and the Internet in most of the country, leaving resistance forces isolated from the outside world and making it difficult for the various armies to coordinate with one another. Despite being severely outnumbered and

Small and medium enterprises make up the backbone of Taiwan’s economy, yet large corporations such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) play a crucial role in shaping its industrial structure, economic development and global standing. The company reported a record net profit of NT$374.68 billion (US$11.41 billion) for the fourth quarter last year, a 57 percent year-on-year increase, with revenue reaching NT$868.46 billion, a 39 percent increase. Taiwan’s GDP last year was about NT$24.62 trillion, according to the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, meaning TSMC’s quarterly revenue alone accounted for about 3.5 percent of Taiwan’s GDP last year, with the company’s