Behind most visions of a high-tech future, there is an assumption that energy would become super-abundant. Take Wakanda, the secretly rich, technologically advanced nation portrayed in Marvel’s Black Panther series. With its flying cars, maglev trains, and levitating, invisibility-shielded fighter aircraft, it is positively dripping in the power gleaned from deposits of the fictional metal vibranium.

The reality across today’s Africa could not be more different. Living without a plug socket is rapidly becoming an almost exclusively African problem: Of the 685 million people globally without access to power, 571 million live there. Just five countries outside the continent — Haiti, Myanmar, North Korea, Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu — have been unable to give more than three-quarters of their population access to electricity. In sub-Saharan Africa, 39 out of 45 nations fail that test.

The significance of this problem becomes apparent when you consider how indispensable energy is as the fuel for economic growth. There is no rich country on the planet that does not use it to a lavish extent.

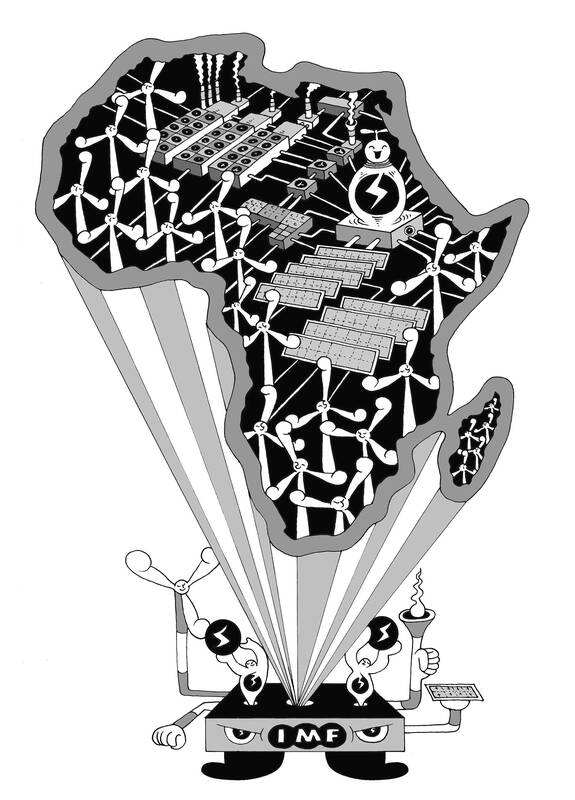

Illustration: Mountain People

Each year, fast-growing middle-income countries such as India and Indonesia use about 30 gigajoules (GJ) per capita or more. You start to enjoy rich-country standards of living in the region of 80 GJ/capita to 100 GJ/capita. (The EU stands at about 125 GJ/capita and the US is more than double that.)

Africa is in a quite different place. Its consumption stands at 23 GJ/capita, about where India was 15 years ago — and even this number is flattered by the petroleum-rich nations bordering the Mediterranean and coal-fired South Africa. The sub-Saharan countries in between, where 80 percent of Africans live, mostly get by on about 5 GJ/capita or so.

Population growth over the coming decades is set to make this problem worse. Africa’s energy consumption would expand by about half between now and 2050, the International Energy Agency (IEA) wrote in its annual outlook last week. On a per-capita basis, however, consumption is likely to go backwards, with a drop of about 10 percent from levels already well below every other place on the planet.

That is a disastrous prospect. While the IEA does not break down its numbers by individual countries, such an outcome would leave the average African in 2050 using about the same amount of energy as they did when decolonization began in the 1960s.

In that era, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah and Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser (and the white minority government of modern-day Zimbabwe) built vast hydroelectric projects to drive industrialization. The idea that the region might be heading back to colonial levels of energy scarcity, rather than advancing toward a prosperous 21st century, makes Afrofuturist dreams feel like a bad joke.

What could change this picture? In theory, there is a strong case for Africa to be given a pass on fossil-fuel development. With about one-fifth of the global population, the continent has contributed just 3 percent or so of historic emissions. A group of oil-producing countries is seeking to set up a US$5 billion “energy bank” for projects that rich countries would no longer lend money to support, the Financial Times reported last week.

That might be justifiable in moral terms. The problem is geology and economics. Outside of South Africa, the continent is notably poorly endowed with coal reserves, the cheap and dirty fuel that powered the initial stages of China’s and India’s growth.

It is in a better situation with petroleum (Africa’s oil reserves, at about 125 billion barrels, are more than twice those of Asia, Europe and Oceania put together), but, in keeping with a long history of extractive industries, that resource is better exported to bring in foreign exchange than used at home.

Nuclear faces comparable challenges. There is just a single atomic power station on the continent, a five-decade-old plant in South Africa. In a region where funding is scarce and expensive, such a capital-intensive power source is unlikely to get far.

That leaves renewables — and here, at least, there are promising prospects in a region baked by the sun, strafed with winds, bisected by a volcanic rift valley that offers potential for geothermal power, and rich in hydroelectricity from the highlands of Ethiopia to the downstream rapids of the Congo.

However, renewables face similar finance problems to nuclear, in addition to unique issues around regulation: African countries impose tariffs and other trade barriers on wind and solar equipment at almost three times the levels in rich countries, and more than twice those in Asia and Latin America, a UN Trade and Development report last week said.

Solar projects in Ghana must be made with 60 percent local content. Such requirements might just be a small hurdle in countries with relatively vibrant manufacturing sectors, such as the US or India. In Ghana, they could resemble a de facto ban.

If those barriers could be reduced, there would be a real opportunity. China’s rapid expansion of wind and solar manufacturing means there is no shortage of increasingly cheap clean energy equipment out there. If it is serious about development, the IMF should recognize the urgency of the situation and the potential of a solution by using its quasi-currency as a form of quantitative easing for African energy.

Africa’s 1.5 billion people lack access to the clean, abundant energy to which they are entitled. That cannot be allowed to continue. The current situation is holding back a region that was the cradle of humanity, and should be its future.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering climate change and energy. Previously, he worked for Bloomberg News, the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention. If it makes headlines, it is because China wants to invade. Yet, those who find their way here by some twist of fate often fall in love. If you ask them why, some cite numbers showing it is one of the freest and safest countries in the world. Others talk about something harder to name: The quiet order of queues, the shared umbrellas for anyone caught in the rain, the way people stand so elderly riders can sit, the

Taiwan’s fall would be “a disaster for American interests,” US President Donald Trump’s nominee for undersecretary of defense for policy Elbridge Colby said at his Senate confirmation hearing on Tuesday last week, as he warned of the “dramatic deterioration of military balance” in the western Pacific. The Republic of China (Taiwan) is indeed facing a unique and acute threat from the Chinese Communist Party’s rising military adventurism, which is why Taiwan has been bolstering its defenses. As US Senator Tom Cotton rightly pointed out in the same hearing, “[although] Taiwan’s defense spending is still inadequate ... [it] has been trending upwards

Small and medium enterprises make up the backbone of Taiwan’s economy, yet large corporations such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) play a crucial role in shaping its industrial structure, economic development and global standing. The company reported a record net profit of NT$374.68 billion (US$11.41 billion) for the fourth quarter last year, a 57 percent year-on-year increase, with revenue reaching NT$868.46 billion, a 39 percent increase. Taiwan’s GDP last year was about NT$24.62 trillion, according to the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, meaning TSMC’s quarterly revenue alone accounted for about 3.5 percent of Taiwan’s GDP last year, with the company’s

In an eloquently written piece published on Sunday, French-Taiwanese education and policy consultant Ninon Godefroy presents an interesting take on the Taiwanese character, as viewed from the eyes of an — at least partial — outsider. She muses that the non-assuming and quiet efficiency of a particularly Taiwanese approach to life and work is behind the global success stories of two very different Taiwanese institutions: Din Tai Fung and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC). Godefroy said that it is this “humble” approach that endears the nation to visitors, over and above any big ticket attractions that other countries may have