The EU’s biggest banks have spent years quietly creating a new way to pay that could finally allow customers to ditch their Visa Inc and Mastercard Inc cards — the latest sign that the region is looking to dislodge two of the most valuable financial firms on the planet.

Wero, as the project is known, is now rolling out across much of western Europe. Backed by 16 major banks and payment processors including BNP Paribas SA, Deutsche Bank AG and Worldline SA, the platform would eventually allow a German customer to instantly settle up with, say, a hotel in France using their own bank account instead of a Visa or Mastercard.

That might sound simple, but if the firms pull it off, it could end up costing the two payment giants billions of dollars of the fees they reap from European merchants each time consumers swipe one of their cards at checkout.

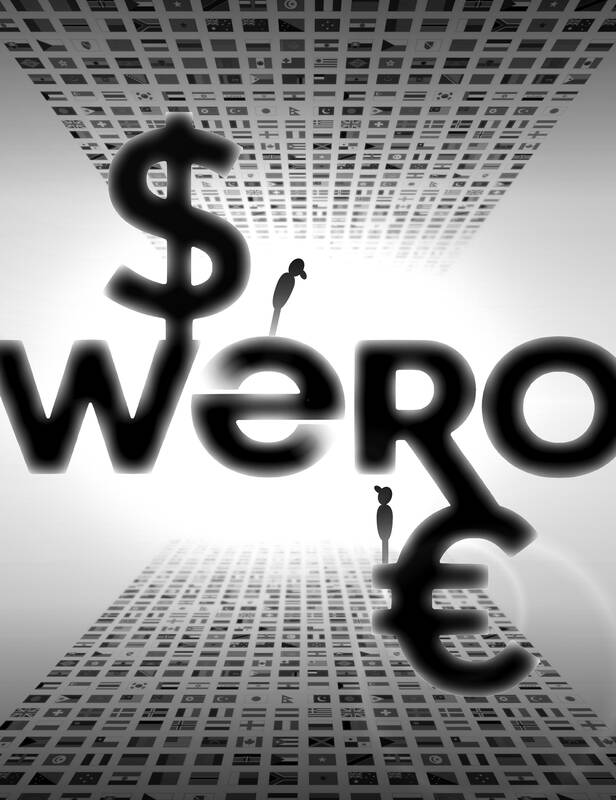

Illustration: Yusha

However, more importantly, it is an example of Europe’s unease about relying on the US for key pieces of infrastructure — financial or otherwise. Ever since Russia invaded Ukraine and the two networks yanked the country’s ability to conduct everyday payments, governments around the world have been wary of deepening their reliance on them.

“Visa and Mastercard being so big, they have in their hands a lot of market control power,” said Martina Weimert, chief executive officer of European Payments Initiative (EPI), the company behind Wero.

The idea is to build up an “alternative to international solutions in order to offer European players and consumers a European choice.”

Wero has a long way to go before it stacks up against Visa and Mastercard, which together process tens of trillions of dollars globally every year, or even the new generation of digital payment firms competing fiercely for consumers moving money. Weimert conceded that “it would be very presumptuous” to call the firm a challenger.

“We are a kind of a start-up,” she said, albeit one that already has 500 million euros (US$558.4 million) from its backers and a ready-made customer base from its banking participants.

Within days of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Visa and Mastercard moved swiftly to suspend their operations, preventing overseas payments by Russian cardholders and halting foreigners from making transactions on Russian soil.

Russia’s central bank, ready for this sort of crisis, had previously created the Russian National Payment Card System to process transactions domestically, even if the cards carried a Visa or Mastercard logo. This workaround meant consumers could continue to make payments locally after the invasion.

“For those people who are interested in Mastercard, you should be interested in what the nationalistic tendencies are around the world,” Mastercard CEO Michael Miebach told investors on a conference call last year. “There are countries who are sitting and saying: ‘What will happen to us if a similar kind of situation as Russia played out?’ Which has got nothing to do with Mastercard, per se, but it’s got everything to do with the political environment which we’re operating in.”

Even before the networks’ showdown with Russia, the European Central Bank had grown worried that it lacked sufficient sovereignty over its payments systems. That is where EPI is supposed to come in.

Plenty of national challengers have emerged in Europe over the years, such as Swish in Sweden, Twint in Switzerland and iDeal in the Netherlands. However, none of them are quite as ubiquitous as Visa or Mastercard — for instance, iDeal handles 70 percent of online commerce in the Netherlands, but does not yet allow consumers to make payments in stores. Often, Europeans cannot use these tools in neighboring countries, so they are forced to opt for US brands.

Wero, which acquired iDeal as well as Luxembourg-based Payconiq last year, seeks to plug those gaps, the banks say. Its services would be available both through its own app and through participating lenders’ platforms.

“Payments is a matter of volumes. If you don’t have volumes, you don’t have the capacity to be competitive” on user experience, said Carlo Bovero, BNP Paribas’s global head of cards and innovative payments.

The bank has more than 35 million subscribers for its Paylib payments service in France, who are being folded into Wero.

To be sure, Europe has stumbled with its previous attempts in this space. The Monnet project sought to create a pan-European card brand, but folded over a decade ago after disagreements over the business model. EPI started in 2020 with a similar idea but was forced to narrow its scope as Spanish banks dropped out of the alliance.

It decided instead to start with account-to-account payments as this was cheaper and easier for member banks to integrate. EU regulations for instant payments, mandating banks to process money transfers within 10 seconds, made that focus more pressing. Next year, it wants to expand into e-commerce and offer in-store payments with retailers across the continent after that.

“It is the right step forward for Europe, apart from everything else that we bring to the European level, to also consider payments more holistically through a European lens,” said Ole Matthiessen, Deutsche Bank’s global head of cash management and head of corporate banking in Asia-Pacific, Middle East and Africa.

Matthiessen sits on the EPI board.

“The issue of payment sovereignty is also a political one,” he said.

Some of the building blocks for easy cross-border payments already exist in the form of the euro, which is now accepted in more than 20 countries. Still, in the digital space, “local payment methods have become the standard,” Matthiessen added. “Now we have to bring it to the front end and make it more convenient for the end user. There are still too many users ultimately using offerings from either the US or the East, China particularly.”

Visa and Mastercard, founded by banks in the 1950s and 1960s as an alternative to cash, processed US$14.8 trillion and about US$9 trillion respectively last year, taking a cut for handling transactions. The two companies have been under fire from regulators, customers and lawmakers worldwide for the fees they charge.

It is a volatile time to be a global payment company as numerous regional rivals emerge. Seven major US banks including JPMorgan Chase & Co and Wells Fargo & Co have coalesced around Zelle, a system that offers speedier transactions between accounts. It had grown to 120 million accounts by last year and competes with the likes of PayPal Holdings Inc.

In Brazil, the central bank’s instant-payment system Pix grew along with COVID-19 pandemic-driven online shopping and is now targeting Brazilian tourists in Europe. The Indian government-backed Unified Payments Interface (UPI), crossed 100 billion total transactions last year after eight years in operation.

In Asia, the Bank for International Settlements has this year started work on Project Nexus for instant cross-border payments between Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and India. Meanwhile online wallets such as China’s AliPay and WeChat Pay along with Apple Pay and Google Pay continue to expand.

Overall, payments revenues grew at an annual rate of 8.3 percent from 2017 to 2022, taking the revenue pool to US$1.6 trillion, Boston Consulting Group data showed.

Consumers have plenty of other options in their wallets and smartphones, making it a challenge for Wero to find a place, even if its speed and lower costs make it “likely that merchants will adopt the technology,” Sonja Forster and Elisabeth Rudman from Morningstar DBRS said in a July note.

For now, Visa and Mastercard have by far the biggest heft and can afford to be gracious about their challengers.

“I look at EPI as it’s yet another solution, and we welcome that,” Miebach said in an interview. “At the same time, we want to put out Mastercard payment solutions that give the consumer a reason to make a choice to use our product versus somebody else’s. So, I’m not particularly worried about it. We know what it takes to invest and scale a business. It’s very hard to do.”

He said that “the principles of choice and competition are good ones” for the European payments landscape, a sentiment shared by executives at Visa.

“The competitive landscape in Europe has never been richer and for me EPI is one of those solutions,” said Charlotte Hogg, chief executive officer for Visa’s European operations.

She pointed to a bundle of regulatory changes about a decade ago aimed at cracking open competition in finance for helping to stir up the market.

“What doesn’t exist despite the growth of open banking — and there’re now 500 of these players across Europe — is the rules of the road for payments in terms of what happens when they go right and what happens when they go wrong,” Hogg said.

There are moments in history when America has turned its back on its principles and withdrawn from past commitments in service of higher goals. For example, US-Soviet Cold War competition compelled America to make a range of deals with unsavory and undemocratic figures across Latin America and Africa in service of geostrategic aims. The United States overlooked mass atrocities against the Bengali population in modern-day Bangladesh in the early 1970s in service of its tilt toward Pakistan, a relationship the Nixon administration deemed critical to its larger aims in developing relations with China. Then, of course, America switched diplomatic recognition

The international women’s soccer match between Taiwan and New Zealand at the Kaohsiung Nanzih Football Stadium, scheduled for Tuesday last week, was canceled at the last minute amid safety concerns over poor field conditions raised by the visiting team. The Football Ferns, as New Zealand’s women’s soccer team are known, had arrived in Taiwan one week earlier to prepare and soon raised their concerns. Efforts were made to improve the field, but the replacement patches of grass could not grow fast enough. The Football Ferns canceled the closed-door training match and then days later, the main event against Team Taiwan. The safety

The National Immigration Agency on Tuesday said it had notified some naturalized citizens from China that they still had to renounce their People’s Republic of China (PRC) citizenship. They must provide proof that they have canceled their household registration in China within three months of the receipt of the notice. If they do not, the agency said it would cancel their household registration in Taiwan. Chinese are required to give up their PRC citizenship and household registration to become Republic of China (ROC) nationals, Mainland Affairs Council Minister Chiu Chui-cheng (邱垂正) said. He was referring to Article 9-1 of the Act

The Chinese government on March 29 sent shock waves through the Tibetan Buddhist community by announcing the untimely death of one of its most revered spiritual figures, Hungkar Dorje Rinpoche. His sudden passing in Vietnam raised widespread suspicion and concern among his followers, who demanded an investigation. International human rights organization Human Rights Watch joined their call and urged a thorough investigation into his death, highlighting the potential involvement of the Chinese government. At just 56 years old, Rinpoche was influential not only as a spiritual leader, but also for his steadfast efforts to preserve and promote Tibetan identity and cultural