Pope Francis is making an Asia-Pacific tour that is about more than spreading the word or connecting with the devout. It is a run-through for the ultimate prize the Roman Catholic Church covets: a trip to China.

By some estimates, the world’s second-largest economy is on track to have the biggest population of Christians by 2030. The pope has been keen to engage with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which has historically controlled the appointment of bishops in the country, independent of the Vatican. This has led to worries of a schism, one of the many reasons the pontiff wants to unify China’s Catholics.

His overtures come despite the nation’s worsening track record on religious freedoms. Any future outreach cannot downplay these concerns, or compromise the Vatican’s diplomatic relations with Taiwan, one of the few remaining examples of recognition that the country still has.

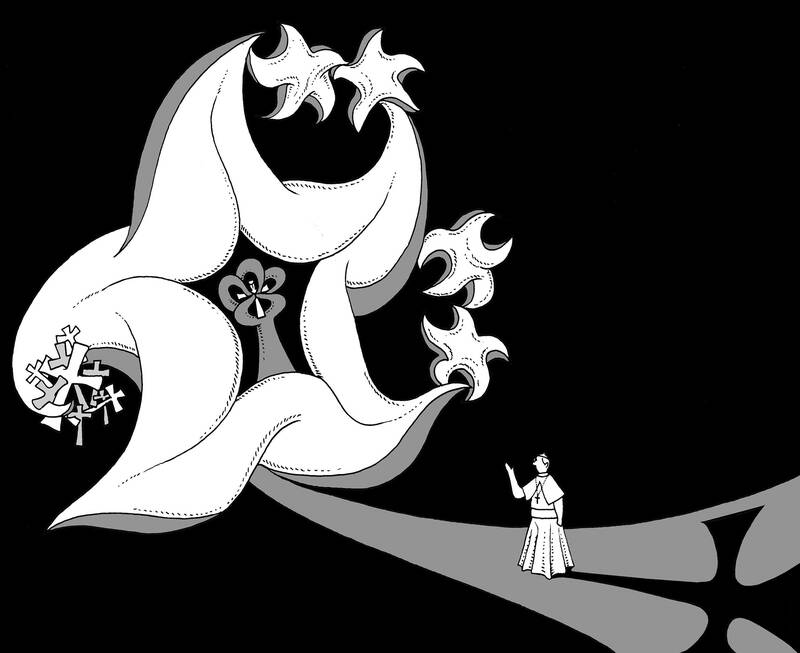

Illustration: Mountain People

No pope has ever visited China, and the Holy See does not have official diplomatic relations with it, despite pursuing closer ties over the past few years. The trip is being viewed as a way to engage with Beijing, but that should not discount the importance of Francis’ current tour to four Asian nations, many of which have sizeable Catholic populations: Indonesia (3 percent, 8 million), Papua New Guinea (26 percent, approximately 3 million), East Timor (97 percent, 1.5 million) and Singapore — home to almost 400,000 Catholics, or 7 percent of the population, many ethnically Chinese — and the last leg of his historic voyage this week.

‘RELIGIOUS FREEDOM’

Still, China is watching very closely. The CCP is officially atheist, and forbids its members from having a religion. However, that dogma has evolved over time and the current constitution, adopted in 1982, states that ordinary citizens enjoy “freedom of religious beliefs.”

What this means in practice, though, is that all faiths are under Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) control. His Sinicization program, introduced in 2015, stipulates religious groups must adapt to socialism, by integrating their beliefs and customs with Chinese culture and political ideology. So in other words, you have the right to worship — but with Chinese characteristics.

“This is not the China of the past, there is no systematic enforcement of atheism now,” said Michel Chambon, research fellow at the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore. “The party is not interested in how you celebrate Mass. Officials just want to ensure that Catholic networks cannot be mobilized against them.”

The relationship between the church and China is complex. Religion was essentially banned during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s, but flourished in the 1980s after the country entered an era of economic reforms. About 2 percent of Chinese adults, or about 20 million people, self-identify with Christianity, the 2018 Chinese General Social Survey showed. Protestants account for roughly 90 percent of those, while the remainder are mostly Catholics.

A 2022 US Department of State report said that there were some 10 million to 12 million Catholics, adding that many have to practice their faith in secret, away from the scrutiny of officials. Those who refuse to join the government’s Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association or pledge allegiance to the party were harassed, detained, disappeared or imprisoned, it said.

Reaching out to the faithful is one reason behind the Vatican’s overtures to China, but it is also about winning hearts and minds among believers divided into two groups: one under a state-controlled church and the other that worships in “underground churches” whose bishops are not approved by Chinese authorities.

The Holy See has been fighting a battle with Beijing about who gets to appoint bishops, and in 2018 reached a compromise — candidates recognized by both would be appointed. For the Vatican, it was a way to bring more Chinese Catholics into the fold, but some high-profile figures in the church, including the now retired Cardinal Joseph Zen (陳日君) of Hong Kong, worried it had ceded too much power.

At the time, Zen told Bloomberg that the pontiff was too optimistic about the Chinese government and warned that closer ties “will have tragic and long-lasting effects, not only for the church in China, but for the whole church.”

His remarks were prescient. In 2022, Zen was fined after being found guilty on a charge relating to his role in a relief fund for Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests in 2019, which he denied.

Taiwan is a pressing dilemma. The Vatican is among 12 diplomatic allies that Taiwan still has left. There are concerns these loyalties could shift, as the Holy See attempts to improve ties with Beijing. Regular meetings between Chinese clergy and their counterparts in Rome, a trend toward normalizing relations, and even discussions about setting up a “stable presence” by the Vatican in China, all point to an upgrading of that relationship.

DUAL RECOGNITION?

Beijing’s efforts to switch international allegiances away from Taipei have been remarkably successful. Getting the Vatican on its side would be a high-profile victory, but the church has consistently maintained that it would never abandon Taipei. It is conceivable, given its religious authority, that it could have spiritual ties with both, and some Taiwanese have even asked the Holy See to press for “dual recognition.”

China will not make that easy, given its animosity toward Taiwan. The Vatican wants to bring all Catholics in China under its umbrella, but that cannot mean a compromise on issues of religious freedom, or a downgrading of its relationship with Taiwan.

The Holy See is Taiwan’s only diplomatic ally in Europe. A pope has never visited there, despite enjoying diplomatic ties for several decades. Casting aside Taiwan for growth in China would seriously damage the church’s credibility as an upholder of spiritual principles.

The Vatican should be transparent about its agreements with Beijing rather than compromise to get deeper access in the country. Consistently voicing concerns about the treatment of the oppressed — a key moral value — should be part of any dialogue with the Communist Party.

As adherence to spirituality declines in the West, growth in the number of faithful will most likely come from Asia. Sacrificing principles for progress is not the way.

Karishma Vaswani is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asia politics with a special focus on China. Previously, she was the BBC’s lead Asia presenter and worked for the BBC across Asia and South Asia for two decades. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

The Chinese government on March 29 sent shock waves through the Tibetan Buddhist community by announcing the untimely death of one of its most revered spiritual figures, Hungkar Dorje Rinpoche. His sudden passing in Vietnam raised widespread suspicion and concern among his followers, who demanded an investigation. International human rights organization Human Rights Watch joined their call and urged a thorough investigation into his death, highlighting the potential involvement of the Chinese government. At just 56 years old, Rinpoche was influential not only as a spiritual leader, but also for his steadfast efforts to preserve and promote Tibetan identity and cultural

Former minister of culture Lung Ying-tai (龍應台) has long wielded influence through the power of words. Her articles once served as a moral compass for a society in transition. However, as her April 1 guest article in the New York Times, “The Clock Is Ticking for Taiwan,” makes all too clear, even celebrated prose can mislead when romanticism clouds political judgement. Lung crafts a narrative that is less an analysis of Taiwan’s geopolitical reality than an exercise in wistful nostalgia. As political scientists and international relations academics, we believe it is crucial to correct the misconceptions embedded in her article,

Sung Chien-liang (宋建樑), the leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) efforts to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Legislator Lee Kun-cheng (李坤城), caused a national outrage and drew diplomatic condemnation on Tuesday after he arrived at the New Taipei City District Prosecutors’ Office dressed in a Nazi uniform. Sung performed a Nazi salute and carried a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf as he arrived to be questioned over allegations of signature forgery in the recall petition. The KMT’s response to the incident has shown a striking lack of contrition and decency. Rather than apologizing and distancing itself from Sung’s actions,

US President Trump weighed into the state of America’s semiconductor manufacturing when he declared, “They [Taiwan] stole it from us. They took it from us, and I don’t blame them. I give them credit.” At a prior White House event President Trump hosted TSMC chairman C.C. Wei (魏哲家), head of the world’s largest and most advanced chip manufacturer, to announce a commitment to invest US$100 billion in America. The president then shifted his previously critical rhetoric on Taiwan and put off tariffs on its chips. Now we learn that the Trump Administration is conducting a “trade investigation” on semiconductors which