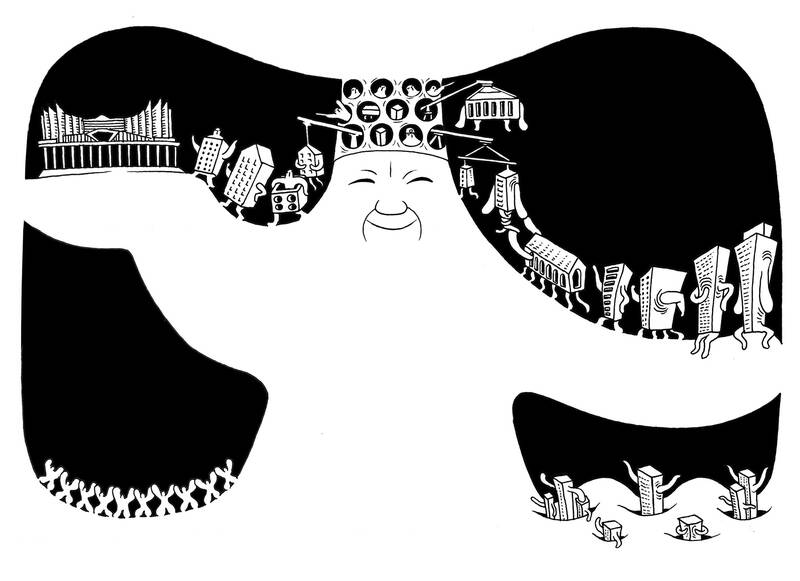

Capital cities do not just happen. They develop slowly over decades, perhaps centuries, before resembling their creator’s dream — if they ever do. Indonesia is discovering such massive endeavors are hard work and prone to delays. Economics has an annoying habit of intruding.

Some of the hype has been deflated from Nusantara, the US$30 billion administrative center that Indonesian President Joko Widodo made one of his signature projects. Erecting the city from scratch in the equatorial forests of Borneo was always going to be arduous. In the past week, authorities made two important concessions: The settlement might not be ready for the first batch of civil servants, and the guest list for national day celebrations had to be scaled back owing to a lack of catering and lodging.

During a visit to the site about 18 months ago, I recognized that the timetable laid out by Jokowi, as the leader is popularly known, would take some doing. There were lots of dirt tracks and trucks, but actual construction was hard to spot. Roads leading to the area from Balikpapan, the nearest urban area, were narrow.

Work has progressed since then, but not as much as hoped. Looming over the project is the approaching end of Jokowi’s second term in October. His successor, Prabowo Subianto, says he is a fan of Nusantara. The challenge is that the capital is not coming cheap and Prabowo has plenty of his own grand plans. Hard choices await.

Jokowi has handed him a budget that is in decent shape. The deficit for next year is projected to be 2.5 percent of GDP, safely within the 3 percent legal limit, the government announced on Friday last week. The outgoing leader is considered to have run a sound fiscal policy during his decade in office. Jokowi has been aided in this task by Indonesian Minister of Finance Sri Mulyani Indrawati, who is highly regarded by foreign investors. The one truly risky move, during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, was the central bank’s direct purchase of bonds from the government — a monetization of debt. That was a practice long shunned in polite economic circles. In a more normal environment, such a step might not be so easily forgiven.

Prabowo, a former top general, has bristled at spending restraints and has pledged a major boost to economic growth. He wants an annual increase in GDP of 8 percent; the figure has been closer to 5 percent over the past decade. It is hard to know whether he really believes this is possible or merely an expression of his ambition. Every time Prabowo expresses frustration at Indonesia’s narrow path, aides clean up the mess by expressing fealty to the rules and tamping down market anxiety. His choice of finance minister will be critical.

The president-elect has promised to finish Nusantara, the first stage of which was scheduled for completion this year. Jokowi envisages close to 2 million people living and working there by 2045. How deep is this commitment?

“I’ve told him Nusantara development will take 10, 15, 20 years,” Jokowi told reporters last week. “He said: ‘That’s not fast enough for me — I want four, five, six years.’ It’s up to him.”

Taken at face value, this puts stress on Prabowo’s own agenda, including a US$29 billion pledge of free meals for schoolchildren.

The idea of moving the capital from Jakarta, which is congested and sinking, is a sound one, but a whole new place, a few hours flight away on a very different island? This is not like getting the Acela train service between New York and Washington or the three-hour drive from Sydney to Canberra. I grew up in Canberra and lived in Washington. These settlements take a while to get going, and can never be free of vested interests.

The good news is that a degree of reality is intruding on Nusantara. There should be no rush to the finish. Canberra was selected as the site of Australia’s capital in 1913, but construction was hampered by two world wars and depression. Washington was burned by the British during the war of 1812. Building capital cities from the ground up proceeds in fits and starts.

Far better to take a measured approach than to hasten as Brazil did in the late 1950s with Brasilia. The city was one of the massive projects favored by then-Brazilian president Juscelino Kubitschek. They left a legacy of rapid inflation and high debt; an economic crisis that followed ushered in years of military rule.

That is not what Prabowo, the former son-in-law of disgraced autocrat Suharto, wants on his record. This is government, not a sprint.

Daniel Moss is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian economies. Previously, he was executive editor for economics at Bloomberg News. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Trying to force a partnership between Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) and Intel Corp would be a wildly complex ordeal. Already, the reported request from the Trump administration for TSMC to take a controlling stake in Intel’s US factories is facing valid questions about feasibility from all sides. Washington would likely not support a foreign company operating Intel’s domestic factories, Reuters reported — just look at how that is going over in the steel sector. Meanwhile, many in Taiwan are concerned about the company being forced to transfer its bleeding-edge tech capabilities and give up its strategic advantage. This is especially

US President Donald Trump last week announced plans to impose reciprocal tariffs on eight countries. As Taiwan, a key hub for semiconductor manufacturing, is among them, the policy would significantly affect the country. In response, Minister of Economic Affairs J.W. Kuo (郭智輝) dispatched two officials to the US for negotiations, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC) board of directors convened its first-ever meeting in the US. Those developments highlight how the US’ unstable trade policies are posing a growing threat to Taiwan. Can the US truly gain an advantage in chip manufacturing by reversing trade liberalization? Is it realistic to

US President Donald Trump’s second administration has gotten off to a fast start with a blizzard of initiatives focused on domestic commitments made during his campaign. His tariff-based approach to re-ordering global trade in a manner more favorable to the United States appears to be in its infancy, but the significant scale and scope are undeniable. That said, while China looms largest on the list of national security challenges, to date we have heard little from the administration, bar the 10 percent tariffs directed at China, on specific priorities vis-a-vis China. The Congressional hearings for President Trump’s cabinet have, so far,

The US Department of State has removed the phrase “we do not support Taiwan independence” in its updated Taiwan-US relations fact sheet, which instead iterates that “we expect cross-strait differences to be resolved by peaceful means, free from coercion, in a manner acceptable to the people on both sides of the Strait.” This shows a tougher stance rejecting China’s false claims of sovereignty over Taiwan. Since switching formal diplomatic recognition from the Republic of China to the People’s Republic of China in 1979, the US government has continually indicated that it “does not support Taiwan independence.” The phrase was removed in 2022