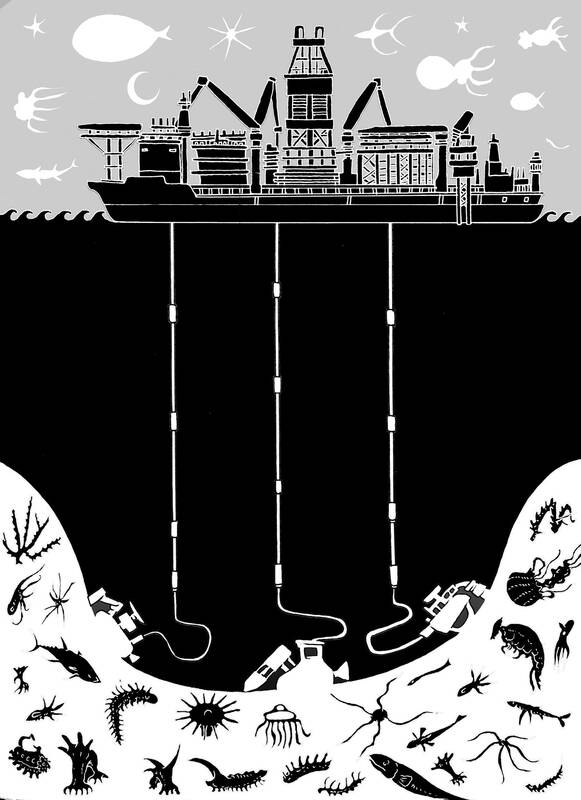

Mining the deep oceans for cobalt, nickel, rare earths and other metals could accelerate the world’s conversion to renewable power sources. These minerals are hard to obtain on land, where mining has also created hazards for communities and workers, but can be found in abundance right on top of the ocean floor.

The problem is that the bottom of the sea is not one uniform environment. It has its own mountains and valleys, and unique ecosystems, some of them unexplored. The areas with all the minerals are among the most mysterious. They are also rich with weird life forms — lobster-sized shrimp and transparent fish, alien-looking anemones and sea urchins that seem to gallop across the seafloor.

One of the companies gearing up to do the mining — Canada-based The Metals Company — is funding research to explore a mineral-rich region called the Clarion-Clipperton zone. It is a vast, oblong patch of seafloor between Mexico and Hawaii, more than 3km below the surface of the Pacific Ocean. What those expeditions turned up was not just weird life, but a whole weird system in which the mineral-containing rocks, which the scientists call nodules, might be generating some of the oxygen that the habitat’s animals are breathing.

Illustration: Mountain People

Deep-sea mining is sometimes portrayed as a story of greedy capitalists versus good scientists, but reality is rarely so clear-cut. As global warming accelerates, we would be faced with countermeasures that lead to other forms of environmental harm. We would have to choose between curbing our consumption and adopting technology in various shades of dirty green.

The deep sea is so hard to reach that scientists and capitalists often end up working together to reach it. For example, findings in a recent Nature Geoscience paper came about in part with funding from The Metals Company.

Lead author and Scottish Association for Marine Science researcher Andrew Sweetman said he noticed something odd during a 2013 expedition to study oxygen consumption in the deep sea.

The oxygen in our planet’s oceans and atmosphere normally comes from photosynthesis. It is too dark for that to happen 3km below the surface of the sea.

Dissolved oxygen can be carried to the deep via currents, where it is used up by living things, Sweetman said. Yet his sensors showed oxygen was also being produced way down there. He had the sensors recalibrated, but they still showed oxygen levels increasing. He told his students to throw the sensors in the waste bin.

Then, in 2021, with funding from The Metals Company, he tried measuring oxygen with a different method involving chemical titration. The increase did not disappear. He and his colleagues then brought up a sample of deep-sea rocks for various experiments. They continued to make oxygen, which he dubbed “dark oxygen.” He considered the possibility that these metal-rich nodules were acting like natural batteries. He teamed up with an electrochemist who helped him measure a voltage — enough to separate water into hydrogen and oxygen.

The nodules grow at the astoundingly slow rate of about a few millimeters per million years, so these undersea environments are tens or hundreds of millions of years old, Sweetman said, adding that some creatures only live on the nodules.

The finding could have big implications for the understanding of the evolution of life on this planet and on other worlds with oceans — including moons of Jupiter and Saturn that NASA has plans to explore.

Not everyone is convinced. One of the researchers employed by The Metals Company told New Scientist he plans to write a rebuttal, saying that it is probably an error from contamination.

For his part, Sweetman does not consider his finding, even if replicated, to be a reason to nix all mining plans — only to wait a little longer to understand the deep sea and how to limit mining to preserve the life down there.

The minerals brought up could accelerate the race to wean ourselves from fossil fuels, he said, adding that climate change effects the seas as well as the land.

“Everyone’s wanting their brand-new cell phone and a brand-new computer and an electric car,” Sweetman said. “We need to make some tough decisions.”

The metals would be useful not just for electric vehicle batteries, but also for systems that store and transport solar and wind energy, Northwestern University biological and chemical engineering professor Jennifer Dunn said. However, artificial intelligence also creates an insatiable market for some of the same hard-to-obtain minerals — which might make it hard to avoid getting greedy.

The trade-offs would not be so stark if people were willing to change their lifestyles. For example, the US could invest in more public transportation — and actually use it.

Dunn recalls the mocking reaction of Americans when former US president Jimmy Carter suggested in 1977 that we turn our thermostats down in the winter and wear sweaters.

She said undersea mining should not be taken off the table, because the consequences of unabated global warming are so dangerous, but we need to know more about the risks. Could there be some unanticipated disaster like the Deepwater Horizon oil spill? Scientists would have to assess not just the environmental impacts if everything went as planned, but also the impacts if things went wrong.

Deep-sea habitats are not going to regenerate once they are disturbed, at least not any time soon — so mining too aggressively could cause irreversible damage, possibly driving species to extinction before humanity even knows they exist. Climate change is, of course, posing the same kind of threat. There are no easy choices ahead of us.

F.D. Flam is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering science. She is host of the Follow the Science podcast.

President William Lai (賴清德) attended a dinner held by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) when representatives from the group visited Taiwan in October. In a speech at the event, Lai highlighted similarities in the geopolitical challenges faced by Israel and Taiwan, saying that the two countries “stand on the front line against authoritarianism.” Lai noted how Taiwan had “immediately condemned” the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas and had provided humanitarian aid. Lai was heavily criticized from some quarters for standing with AIPAC and Israel. On Nov. 4, the Taipei Times published an opinion article (“Speak out on the

Eighty-seven percent of Taiwan’s energy supply this year came from burning fossil fuels, with more than 47 percent of that from gas-fired power generation. The figures attracted international attention since they were in October published in a Reuters report, which highlighted the fragility and structural challenges of Taiwan’s energy sector, accumulated through long-standing policy choices. The nation’s overreliance on natural gas is proving unstable and inadequate. The rising use of natural gas does not project an image of a Taiwan committed to a green energy transition; rather, it seems that Taiwan is attempting to patch up structural gaps in lieu of

News about expanding security cooperation between Israel and Taiwan, including the visits of Deputy Minister of National Defense Po Horng-huei (柏鴻輝) in September and Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) this month, as well as growing ties in areas such as missile defense and cybersecurity, should not be viewed as isolated events. The emphasis on missile defense, including Taiwan’s newly introduced T-Dome project, is simply the most visible sign of a deeper trend that has been taking shape quietly over the past two to three years. Taipei is seeking to expand security and defense cooperation with Israel, something officials

“Can you tell me where the time and motivation will come from to get students to improve their English proficiency in four years of university?” The teacher’s question — not accusatory, just slightly exasperated — was directed at the panelists at the end of a recent conference on English language learning at Taiwanese universities. Perhaps thankfully for the professors on stage, her question was too big for the five minutes remaining. However, it hung over the venue like an ominous cloud on an otherwise sunny-skies day of research into English as a medium of instruction and the government’s Bilingual Nation 2030