Tajik journalist Temur Varki received a disquieting call from Paris police in late March, days after Islamic State militants from his homeland allegedly carried out a massacre in Moscow.

The two officers questioned him about France’s tiny community of immigrants from Tajikistan, an impoverished former Soviet republic in Central Asia.

“Who do you know? How many? Where?” Varki recalled the officers asking, with one of them speaking Russian, a commonly used language across Central Asia. Varki, a political refugee in France who has worked for outlets including the BBC, told the police callers he knew a handful of Tajiks in the country, mainly fellow emigres and dissidents.

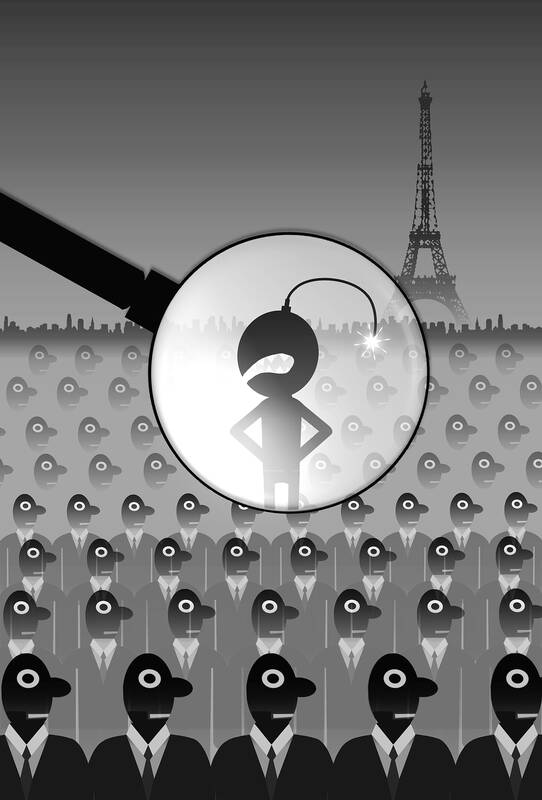

Illustration: Yusha

“But I don’t know any jihadists,” he told them.

Ahead of the Paris Olympics that begin on Friday, French security services have been racing to address an intelligence blind spot and forge deeper ties with Tajiks and other Central Asians in the country, more than a dozen people with knowledge of the drive said. They include current and former intelligence officials, police, diplomats and Central Asian migrants who have been contacted by authorities.

The outreach, which has not been previously reported, comes in the wake of two major attacks this year that authorities say were carried out by Tajik members of ISIS-K, a resurgent wing of the Islamic State, named after the historical region of Khorasan that included parts of Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia.

A double suicide bombing in Iran on Jan. 3 killed about 100 people at a memorial ceremony for slain Iranian Revolutionary Guards commander Qassem Soleimani, while the Moscow tragedy on March 22 saw gunmen open fire at concertgoers at Crocus City Hall, killing more than 130 people.

French authorities say they have already foiled one Islamist attack on the Olympics, with the arrest in late May of an 18-year-old Chechen man suspected of planning a suicide mission on behalf of the Islamic State at Saint-Etienne’s soccer stadium, where France, the US and Ukraine are to play.

With its complex colonial past, lingering anti-Muslim sentiment and historic involvement in Middle Eastern and African wars, France has long been a target of Islamist attacks. Last month, Paris police chief Laurent Nunez said “Islamist terrorism remains our main concern” at the Olympics, although authorities say there have been no direct threats against the Games.

Tajikistan, plagued by civil war in the 1990s, is the poorest of the former Soviet republics. It relies on remittances from migrants — mainly in Russia — for nearly half of its economic output.

Poor, isolated young men among the Tajik diaspora have proven to be an attractive recruiting pool for ISIS-K, many security experts said. Yet French intelligence has few Central Asian assets, an intelligence source told Reuters, adding that it finds their small, tight-knit communities hard to penetrate. France’s Tajik Association said there are about 30 Tajik families living in the country.

ISIS-K represented a relatively new threat, with recruiters/handlers who are based abroad able to remotely radicalize and activate Central Asians in France to carry out attacks on French soil, said the intelligence source, who requested anonymity to discuss security matters.

As evidence, the source pointed to the case of a Tajik man who was arrested in 2022 for plotting an attack in Strasbourg. The man was acting under instruction from ISIS-K handlers based abroad, the source said.

A second security source said France had identified a dozen ISIS-K handlers, based in countries around Afghanistan, who have a strong online presence and try to convince young men in European countries who are interested in joining up with the group overseas to instead carry out domestic attacks.

The handlers then connect the recruits with people who can provide fake IDs and weapons on the ground in the country involved, in a process that can take just a few weeks, the source said.

Reached by Reuters, the two police officers who spoke to Varki declined to comment. Paris police referred questions to the French Ministry of the Interior, which declined to comment.

Tajikistan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not respond to a request for comment.

Along with Varki, Reuters spoke to two other Tajiks and one Uzbek based in France who had been contacted by police and questioned about their communities.

Nadejda Atayeva, an Uzbek human rights activist in the northwestern city of Le Mans, said she gave officials Varki’s phone number after meeting with them at police HQ in Paris.

“I was asked for contacts of Tajiks I trust. I was told that they wanted to talk to Tajiks to get their opinion on the events in Moscow,” she said.

Paris might have been slow to react to the potential Tajik threat, said Sebastien Peyrouse, a French academic who has briefed French and US security agencies on Central Asian militancy.

“France has focused much more on radicalized people coming from the Middle East, from Algeria, from northern Africa, than from Central Asia,” he said. “I think France was pretty surprised by what happened in Moscow and it could be a little bit late.”

Russian intelligence still has the best oversight of Central Asian militant networks, despite failing to prevent the Crocus City Hall attack, said Edward Lemon, a Tajikistan expert who regularly briefs Western spy agencies.

Yet intelligence sharing between Russia and France about Islamic State and other militant groups has been drastically reduced since Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, French Minister of the Armed Forces Sebastien Lecornu said in April.

Two US Department of State officials coordinating with the Olympics security for Team USA told Reuters they were confident in France’s preparations. Without going into specifics, they said French efforts to build deeper ties with its Tajik population reflected a common counterterrorism practice to learn more about possible threatening actors within the community.

“Everybody would like to have” more information on Central Asian threats, one of them said, speaking on condition of anonymity.

The main Tajik militant risk in Europe comes from about a dozen radicalized men who fought in Syria and have slowly filtered back into the continent via Ukraine following the decline of the Islamic State in the Middle East, Lemon and other two other Central Asia experts said in an interview.

Last year, German authorities arrested seven Central Asians living in the country on suspicion of founding a terrorist organization. The Turkmen, Tajik and Kyrgyz nationals entered Germany from Ukraine shortly after the Russian invasion in early 2022, prosecutors said. They are in jail awaiting trial.

Lemon said he estimated there were tens of thousands of Tajiks living in Europe, mainly concentrated in Poland and Germany. Most are political refugees who arrived roughly a decade ago after Tajik President Emomali Rakhmon designated two opposition movements — Group 24 and the Islamic Renaissance Party — as extremist and terrorist organizations. Rakhmon, an ally of Russia, has ruled Tajikistan for 30 years.

Varki, an outspoken Rakhmon critic, said he had sought asylum in France in 2016, because he loved French culture and literature. He said he had never spoken with French security services until the police called him in March.

Another Tajik dissident living in France, Muhammadiqboli Sadriddin, said he, too, had spoken with police.

“They asked me what I knew,” Sadriddin said, adding that he was eager to help but told them: “I do not know Tajiks with a radical opinion.”

France’s efforts to infiltrate the Tajik community could prove counterproductive, three counterintelligence experts told Reuters.

French counterintelligence was generally very well regarded, said a former US spy, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss his time working with French security services on Central Asian issues. However, pressuring Tajiks for information could backfire by stigmatizing them, making them less likely to want to flag risky individuals, he added.

University of Ottawa Islamist militancy specialist Jean-Francois Ratelle agreed.

“This community-building relationship should have been done years ago. If it’s with a counterterrorism mindset, then it’s a recipe for failure,” he said. “If France decides to put too much pressure on that diaspora, it might create the very threat that they are trying to eliminate for the Olympics.”

Additional reporting by Zhifan Liu in Paris, Marco Carta in Rome, Madeline Chambers in Berlin and Jonathan Landay in Washington; editing by Pravin Char.

Chinese actor Alan Yu (于朦朧) died after allegedly falling from a building in Beijing on Sept. 11. The actor’s mysterious death was tightly censored on Chinese social media, with discussions and doubts about the incident quickly erased. Even Hong Kong artist Daniel Chan’s (陳曉東) post questioning the truth about the case was automatically deleted, sparking concern among overseas Chinese-speaking communities about the dark culture and severe censorship in China’s entertainment industry. Yu had been under house arrest for days, and forced to drink with the rich and powerful before he died, reports said. He lost his life in this vicious

George Santayana wrote: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” This article will help readers avoid repeating mistakes by examining four examples from the civil war between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) forces and the Republic of China (ROC) forces that involved two city sieges and two island invasions. The city sieges compared are Changchun (May to October 1948) and Beiping (November 1948 to January 1949, renamed Beijing after its capture), and attempts to invade Kinmen (October 1949) and Hainan (April 1950). Comparing and contrasting these examples, we can learn how Taiwan may prevent a war with

A recent trio of opinion articles in this newspaper reflects the growing anxiety surrounding Washington’s reported request for Taiwan to shift up to 50 percent of its semiconductor production abroad — a process likely to take 10 years, even under the most serious and coordinated effort. Simon H. Tang (湯先鈍) issued a sharp warning (“US trade threatens silicon shield,” Oct. 4, page 8), calling the move a threat to Taiwan’s “silicon shield,” which he argues deters aggression by making Taiwan indispensable. On the same day, Hsiao Hsi-huei (蕭錫惠) (“Responding to US semiconductor policy shift,” Oct. 4, page 8) focused on

In South Korea, the medical cosmetic industry is fiercely competitive and prices are low, attracting beauty enthusiasts from Taiwan. However, basic medical risks are often overlooked. While sharing a meal with friends recently, I heard one mention that his daughter would be going to South Korea for a cosmetic skincare procedure. I felt a twinge of unease at the time, but seeing as it was just a casual conversation among friends, I simply reminded him to prioritize safety. I never thought that, not long after, I would actually encounter a patient in my clinic with a similar situation. She had