Late last month, China’s space program brought back the first rock and soil samples from the mysterious far side of the moon. It was a major triumph. Scientists worldwide are eager to use these samples to learn more about the origin of the moon and Earth.

At the same time, others are worried that China is on the way to winning a new space race for the first permanent base on the moon. China’s mission makes it clear that the country sees the moon as a strategic asset, rather than a site for purely scientific exploration, they said.

So far, China’s lunar ambitions are yielding valuable data that is benefitting the international scientific community and the US space program, which has plans to land the first astronauts on this unexplored part of the moon. The more we earthlings know about this region, the better, so cautious optimism is in order. China’s early success could spur US leaders to put more resources into lunar exploration.

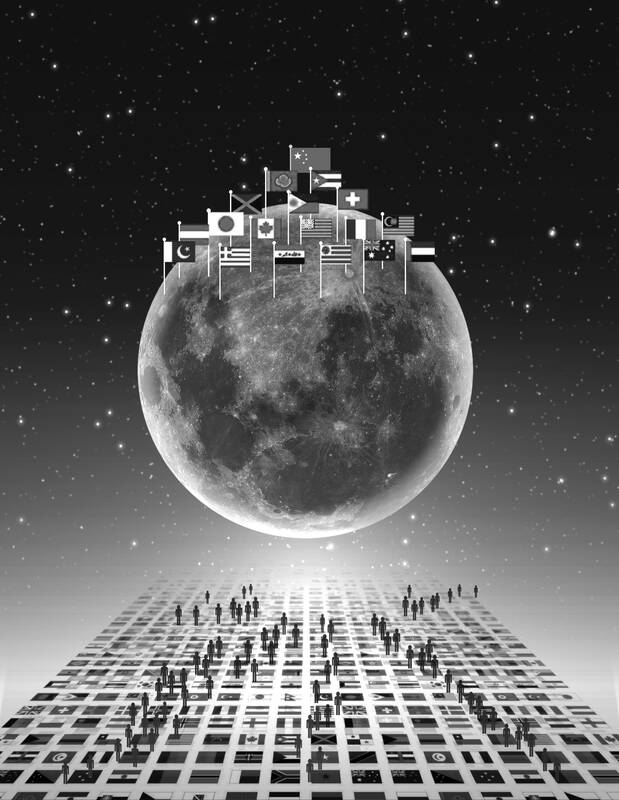

Illustration: Yusha

The main concern is that political tensions would prevent scientists and engineers from engaging in the kind of international collaboration that would make lunar exploration safer and more productive.

At an online briefing called Race to the Moon, held by SpaceNews, several space policy experts said it is crucial for the US to be the first country to establish a moon base, because whoever is first, would set the rules and principles.

Namrata Goswami, coauthor of Scramble for the Skies, said the US would likely establish a more democratic, cooperative system.

China’s craft, Chang’e-6 (嫦娥六號), landed equipment that drilled below the moon’s surface and scooped samples from a region known as the South Pole-Aitken Basin. The mission also put a communication satellite in the lunar orbit, which is necessary to send messages back and forth to any craft on the moon’s far side.

Those who are not cheering this as an advance for science are speculating that China might violate the global outer space treaty and hoard territory or resources. At a US congressional hearing last spring, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson expressed concern that China would claim key lunar territory and exclude everyone else.

The main resource scientists know about on the moon is frozen water lurking in the South Pole-Aitken Basin and other craters nearby — which is why Chang’e-6 landed there. That basin is also the focus of two future missions, Chang’e-7 and Chang’e-8. Those missions would explore the ice in the region and the possibility of extracting water and other resources, with the ultimate goal of building a research outpost.

Not coincidentally, the same region is also the target of the next crewed US mission to the moon — called Artemis — which is supposed to happen sometime this decade.

The water in this region has potential beyond supplying a moon base. Water can also be used as a source of hydrogen to fuel missions aimed further out. The moon, being smaller than Earth, exerts much less gravitational pull on spacecraft, making it a nice launch spot, including for laser-propelled probes that could potentially travel to planets orbiting distant stars.

The far side of the moon has a couple of other resources as well, former NASA Ames Research Center director Simon Peter “Pete” Worden said. One is relative radio silence, allowing an unprecedented chance for radio astronomers to look for remnants of the early universe or even search for alien civilizations.

However, it is too early to start fighting over the moon. We still do not know how much water is hidden near the lunar south pole, said James W. Head, a planetary geologist who chose the sites for the Apollo missions and helped train the astronauts. Head said he is eager to see what analysis of the chemistry and ages of the Chang’e-6 material would tell us.

Flyby missions show the moon’s far side is weirdly different from the near side. The crust is thicker, and the surface lighter, with fewer of the lava flows that make up the darker parts of the moon’s familiar side.

“It’s been a real mystery,” said Head, who is now a professor at Brown University.

Because the moon is not influenced by erosion or plate tectonics, its surface holds a record of the impacts that dominated its early history and ours.

Going back to the moon is an essential step for sending people to Mars, Head said.

“Astronauts who’ve been to the moon will tell you that there’s no way anybody’s going to go to Mars without having field experience on the moon first,” he said.

The world recently got a reminder of the danger and difficulty of space flight when a helium leak and other problems were discovered in the Boeing Starliner during its first crewed mission. The two astronauts who had been aboard the craft have been delayed for weeks aboard the International Space Station.

Boeing last weekend said that the astronauts are in no danger, and could be returned any time, but the company is doing some additional troubleshooting at the White Sands Test Facility in New Mexico, after a new problem emerged with additional helium leaks and the unexpected shutdown of some of the thrusters.

These malfunctions are scary, since they involve keeping people alive in space. Any problems would be more challenging on the moon, which is 1,000 times as far from home as the space station. It would be safer for everyone if China and the US could collaborate and nobody rushes into a dangerous mission.

The US would always have credit for winning the space race more than a half century ago, and there is a vast amount of lunar surface that remains unexplored. A Chinese lunar victory does not necessarily spell disaster for the rest of the world — though it would be bad luck indeed if, out of millions of square kilometers of lunar surface, there is only one bit of real estate suitable for a base.

Exploring the moon with astronauts is difficult and dangerous. Collaboration gives every nation the best shot. However, the public often responds to rivalry, so ironically, it is the perception of a competition with China that could help garner enough public support to get things off the ground.

F.D. Flam is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering science. She is host of the Follow the Science podcast.

China badly misread Japan. It sought to intimidate Tokyo into silence on Taiwan. Instead, it has achieved the opposite by hardening Japanese resolve. By trying to bludgeon a major power like Japan into accepting its “red lines” — above all on Taiwan — China laid bare the raw coercive logic of compellence now driving its foreign policy toward Asian states. From the Taiwan Strait and the East and South China Seas to the Himalayan frontier, Beijing has increasingly relied on economic warfare, diplomatic intimidation and military pressure to bend neighbors to its will. Confident in its growing power, China appeared to believe

After more than three weeks since the Honduran elections took place, its National Electoral Council finally certified the new president of Honduras. During the campaign, the two leading contenders, Nasry Asfura and Salvador Nasralla, who according to the council were separated by 27,026 votes in the final tally, promised to restore diplomatic ties with Taiwan if elected. Nasralla refused to accept the result and said that he would challenge all the irregularities in court. However, with formal recognition from the US and rapid acknowledgment from key regional governments, including Argentina and Panama, a reversal of the results appears institutionally and politically

In 2009, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) made a welcome move to offer in-house contracts to all outsourced employees. It was a step forward for labor relations and the enterprise facing long-standing issues around outsourcing. TSMC founder Morris Chang (張忠謀) once said: “Anything that goes against basic values and principles must be reformed regardless of the cost — on this, there can be no compromise.” The quote is a testament to a core belief of the company’s culture: Injustices must be faced head-on and set right. If TSMC can be clear on its convictions, then should the Ministry of Education

Legislators of the opposition parties, consisting of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), on Friday moved to initiate impeachment proceedings against President William Lai (賴清德). They accused Lai of undermining the nation’s constitutional order and democracy. For anyone who has been paying attention to the actions of the KMT and the TPP in the legislature since they gained a combined majority in February last year, pushing through constitutionally dubious legislation, defunding the Control Yuan and ensuring that the Constitutional Court is unable to operate properly, such an accusation borders the absurd. That they are basing this