It is not hard to understand that global warming is already changing how people live. In India’s capital, New Delhi, this summer has been so hot — above 40°C even at night — that people are gasping, the tap water is scalding and the walls of their homes emit heat like radiators. The Saudi Arabian authorities said that 1,300 pilgrims have already died on this year’s hajj. Players at the European soccer championships are collapsing due to exhaustion.

Yet economists — clearly able to keep cool heads when everybody else is losing theirs — are in the middle of a fresh debate about the real costs of climate change.

A new working paper from two academics at Harvard and Northwestern, and published by the US National Bureau of Economic Research, said that the macroeconomic damage from climate change might be as much as six times higher than previously estimated.

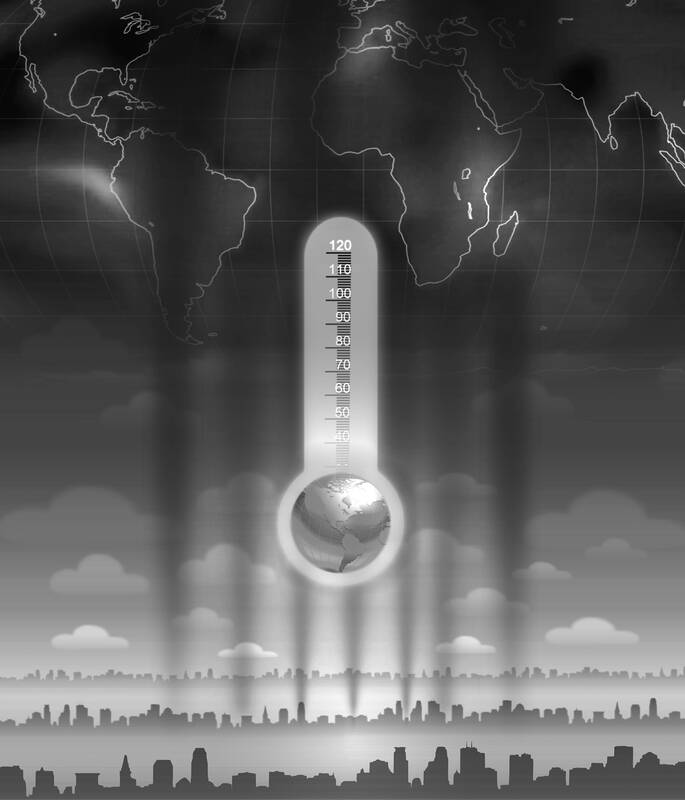

Illustration: Yusha

Their model predicts that a single degree increase “in global mean temperatures leads to a gradual decline in world GDP that peaks at 12 percent after six years and does not fully mean-revert even 10 years after the shock.” They said that this makes unilateral climate action worth it for countries like the US; that argument must surely also hold for countries that are poorer, but far more exposed to climate change, such as India.

The paper has set off a storm of furious criticism, and not just from economists.

Its methodology might be flawed, climate scientist John Kennedy said. For example, he is not sure that scientists can easily extrapolate from the historical record of 0.3°C shocks to global temperature to the larger, 1°C changes associated with climate change.

It is clear that global warming is already having a malign effect on human health and livelihoods. We just need more clarity on how much.

Discussions of the real costs of climate change, to human welfare and to national economies, have been going on for decades. However, politicians no longer need such estimates to make the case that it is real and a problem. Instead, they need them as inputs into policymaking — similar to employment or price data.

Policymakers are still short of objective, sector-specific and precise estimates of current and possible future costs. That shortage is a growing problem — because climate policy is beginning to bite. Billions of taxpayer dollars are being directed to sectors that promise to curb emissions; consumers are paying more for carbon-intensive goods and services; and pressure to follow a net zero strategy has complicated decisions for companies and institutional investors.

These should all count as successes in the fight against climate change. However, when money moves, people begin to ask pointed questions. It is not just various Republican politicians attacking “woke capital” to get in the headlines. Serious macroeconomic decision-makers, accustomed to evidence-based policy, are beginning to ask exactly what global warming’s costs and benefits are for their particular countries.

India’s chief economic adviser, for example, asked earlier this year if we were irrationally scared of the health effects of global warming. It is true that those in India are more exposed to heat stress than most.

However, large-scale studies suggest that far more people die in India as a consequence of “moderate cold” than from extreme heat, he said.

Delhi’s temperature might stay above 40°C for weeks on end, with all the negative effects on public health and economic activity that entails.

However, would other Indians actually live longer if average temperatures rose? Do policymakers have real evidence for the aggregate effect of higher temperatures on mortality in India and the rest of the developing world?

These are real questions that deserve real answers. However, the data scientists currently have are insufficient. That lack of data might lead to erroneous conclusions.

Some academics in India have said that those most exposed to heat stress are manual laborers, construction workers and farmers — marginalized groups whose illnesses and deaths the country’s public health system might not properly record.

It is vital that politicians put more resources into identifying and analyzing the effects of warmer temperatures. Some efforts have already begun: Last year, the WHO released a framework to quantify the economic value of the health outcomes of climate-related investments. Countries such as India must also begin to quantify the many indirect effects of climate change on their macroeconomic fundamentals: from greater variability in farm output to less productive physical investments. Policymakers cannot make evidence-based policy for the greatest global problem of our time without more high-quality data.

Mihir Sharma is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A senior fellow at the Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi, he is author of Restart: The Last Chance for the Indian Economy.

Chinese actor Alan Yu (于朦朧) died after allegedly falling from a building in Beijing on Sept. 11. The actor’s mysterious death was tightly censored on Chinese social media, with discussions and doubts about the incident quickly erased. Even Hong Kong artist Daniel Chan’s (陳曉東) post questioning the truth about the case was automatically deleted, sparking concern among overseas Chinese-speaking communities about the dark culture and severe censorship in China’s entertainment industry. Yu had been under house arrest for days, and forced to drink with the rich and powerful before he died, reports said. He lost his life in this vicious

A recent trio of opinion articles in this newspaper reflects the growing anxiety surrounding Washington’s reported request for Taiwan to shift up to 50 percent of its semiconductor production abroad — a process likely to take 10 years, even under the most serious and coordinated effort. Simon H. Tang (湯先鈍) issued a sharp warning (“US trade threatens silicon shield,” Oct. 4, page 8), calling the move a threat to Taiwan’s “silicon shield,” which he argues deters aggression by making Taiwan indispensable. On the same day, Hsiao Hsi-huei (蕭錫惠) (“Responding to US semiconductor policy shift,” Oct. 4, page 8) focused on

George Santayana wrote: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” This article will help readers avoid repeating mistakes by examining four examples from the civil war between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) forces and the Republic of China (ROC) forces that involved two city sieges and two island invasions. The city sieges compared are Changchun (May to October 1948) and Beiping (November 1948 to January 1949, renamed Beijing after its capture), and attempts to invade Kinmen (October 1949) and Hainan (April 1950). Comparing and contrasting these examples, we can learn how Taiwan may prevent a war with

In South Korea, the medical cosmetic industry is fiercely competitive and prices are low, attracting beauty enthusiasts from Taiwan. However, basic medical risks are often overlooked. While sharing a meal with friends recently, I heard one mention that his daughter would be going to South Korea for a cosmetic skincare procedure. I felt a twinge of unease at the time, but seeing as it was just a casual conversation among friends, I simply reminded him to prioritize safety. I never thought that, not long after, I would actually encounter a patient in my clinic with a similar situation. She had