Although his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) did not roll to the landslide victory he hoped for, Narendra Modi has secured a rare third five-year term as India’s prime minister.

It was not an easy win.

High inflation and unemployment helped a more unified opposition portray Modi as too cozy with big business, reducing his BJP-led alliance’s margin of victory. Growing wealth inequality forced Modi to lean more heavily on the appeal of an often-ugly Hindu nationalism, a burden he has allowed subordinates to carry in the past.

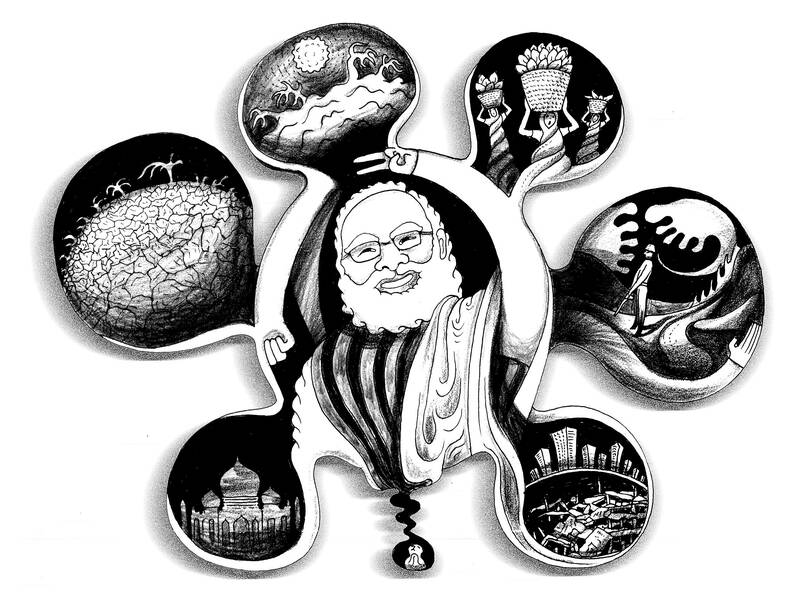

Illustration: Mountain People

In addition, India’s media environment has become more polarized, with many more people getting their news online than when Modi was first elected a decade ago.

However, Modi himself remains far more popular than his party. He has built a reputation for personal integrity and after a decade in office, his name recognition is uncontestable.

That matters in a country with dozens of different languages spoken by millions of people.

Once the votes were counted in the world’s largest and longest-running election, Modi emerged again as the man of the moment.

India needs a popular leader because the long-term challenges it faces are formidable. Within 10 years, India will confront serious water shortages and there is no obvious fix. Modi must work with weak local governments, many of which depend for political support on farming interests that rely too heavily on water-intensive agriculture in areas where water is already in short supply.

Then there is climate change. India has already set temperature records this summer, and hundreds of millions of Indians have no way to escape the heat and humidity.

Add some of the world’s worst air quality, a problem that will become much worse given the enormous amount of power — much of it generated in coal-fired plants — needed to sustain the country’s expected robust economic growth.

The result will be an increase in human suffering in a country with more than its share of environmental damage.

There is also a major structural problem with India’s economy: Not many women contribute to it. Fewer than one-third of employable women are now in the workforce. There are very few female CEOs or corporate board members and a tiny fraction of the country’s venture-capital funding goes to start-ups founded or led by women.

The World Economic Forum’s most recent Global Gender Gap Report ranked India 127th out of 146 countries, behind its neighbors Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. To solve this problem, Modi and other local officials must contend with a large rural population, crippling poverty and conservative social values.

Many tout India’s strong demographics as a crucial economic advantage, particularly when compared with China, Japan and some of Europe’s largest economies, but when half the population face the obstacles to joining the formal economy that India’s women do, the advantage is far from being realized.

Finally, India has 1.5 billion people and too many still live in poverty. Last year, India ranked 111th out of 125 countries on the Global Hunger Index. While China has become an upper-middle-income country, India’s path toward that status is far from secure.

Given its many structural challenges, India could fail to develop as Modi promises, leaving the country more vulnerable to social and political instability, fueled in part by the Hindu nationalism that Modi himself has amplified.

At the same time, India’s geopolitical position confers many advantages. Modi’s government will continue to benefit from the trend that many Indians call “China +1” — the popularity in many Western and Asian countries of limiting production and supply-chain risks associated with China by shifting business operations and investment toward its neighbor. Many multinational corporations across a variety of key economic sectors now see India not only as a viable alternative for long-term capital investment, but as an attractive market in its own right.

Although India’s domestic infrastructure investment continues to lag behind China, the gap is narrowing. In Mumbai, major new highways, bridges and tunnels are easing some of the world’s worst urban traffic. There are fewer interruptions of electricity, communications and the Internet. India is not China, but its day-to-day business operations are no longer regularly disrupted.

India has also made gains in higher-end manufacturing and now exports more motorcycles, cars and other goods that meet once-unimaginable quality standards.

India’s biggest foreign-policy challenges are on its borders with China, Pakistan and Myanmar. All three countries create security problems.

However, outside India’s neighborhood, Modi sees important opportunities.

That is true not only in relations with the US — India is one of the few countries that can expect increasingly close ties with Washington no matter who wins the November presidential election in the US — but especially in the Global South, where Modi has earned a leadership role.

As was seen last year when India hosted the G20 summit, Modi wants India to become a vitally important bridge between the developed and developing worlds.

Since the Cold War’s end, no country’s rise has been welcomed by so many other governments.

In short, India still faces enormous long-term challenges, but Modi’s personal appeal at home and the inroads he has helped establish for India abroad will make his country’s development one of the most important stories of the next decade.

Ian Bremmer, founder and president of Eurasia Group and GZERO Media, is a member of the Executive Committee of the UN High-level Advisory Body on Artificial Intelligence.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

President William Lai (賴清德) attended a dinner held by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) when representatives from the group visited Taiwan in October. In a speech at the event, Lai highlighted similarities in the geopolitical challenges faced by Israel and Taiwan, saying that the two countries “stand on the front line against authoritarianism.” Lai noted how Taiwan had “immediately condemned” the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas and had provided humanitarian aid. Lai was heavily criticized from some quarters for standing with AIPAC and Israel. On Nov. 4, the Taipei Times published an opinion article (“Speak out on the

More than a week after Hondurans voted, the country still does not know who will be its next president. The Honduran National Electoral Council has not declared a winner, and the transmission of results has experienced repeated malfunctions that interrupted updates for almost 24 hours at times. The delay has become the second-longest post-electoral silence since the election of former Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernandez of the National Party in 2017, which was tainted by accusations of fraud. Once again, this has raised concerns among observers, civil society groups and the international community. The preliminary results remain close, but both

News about expanding security cooperation between Israel and Taiwan, including the visits of Deputy Minister of National Defense Po Horng-huei (柏鴻輝) in September and Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) this month, as well as growing ties in areas such as missile defense and cybersecurity, should not be viewed as isolated events. The emphasis on missile defense, including Taiwan’s newly introduced T-Dome project, is simply the most visible sign of a deeper trend that has been taking shape quietly over the past two to three years. Taipei is seeking to expand security and defense cooperation with Israel, something officials

Eighty-seven percent of Taiwan’s energy supply this year came from burning fossil fuels, with more than 47 percent of that from gas-fired power generation. The figures attracted international attention since they were in October published in a Reuters report, which highlighted the fragility and structural challenges of Taiwan’s energy sector, accumulated through long-standing policy choices. The nation’s overreliance on natural gas is proving unstable and inadequate. The rising use of natural gas does not project an image of a Taiwan committed to a green energy transition; rather, it seems that Taiwan is attempting to patch up structural gaps in lieu of