Sicily’s tourist hot spots are living an economic boom thanks to shows like HBO’s The White Lotus, which put the island’s breathtaking vistas on display. However, the ancient island’s infamous underbelly remains untouched by the influx of new wealth. In fact, organized crime has only diversified and become more entwined with the legitimate economy.

On a recent trip to Sicily, the contrast between the flourishing tourism sector and the declines elsewhere was as stark as I have seen in more than 20 years of reporting on the island. In Palermo, the piazza around the cathedral was brimming with activity. Not 10 minutes’ walk away, burnt-out cars lined a residential street of dilapidated high-rise apartments. In Taormina, with its Greco-Roman theater and views over Mount Etna, locals told me new Louis Vuitton and Prada stores had brought more well-heeled visitors to the hilltop town that has a starring role in the second series of the hit HBO show. Yet down the hill and along the coast, piles of filthy refuse made beaches unusable.

Sicily and organized crime — the island’s Cosa Nostra — have been synonymous since at least the 19th century. Atrocities dwindled in recent years following an aggressive campaign by police in response to the 1992 roadside bombs near Palermo that killed prosecuting magistrates Paolo Borsellino and Giovanni Falcone. However, magistrates say it is also because the Sicilian mafia and its Calabrian counterpart, ’Ndrangheta, have grown more sophisticated, following the money into drugs, prostitution and people trafficking rather than open confrontation with the authorities.

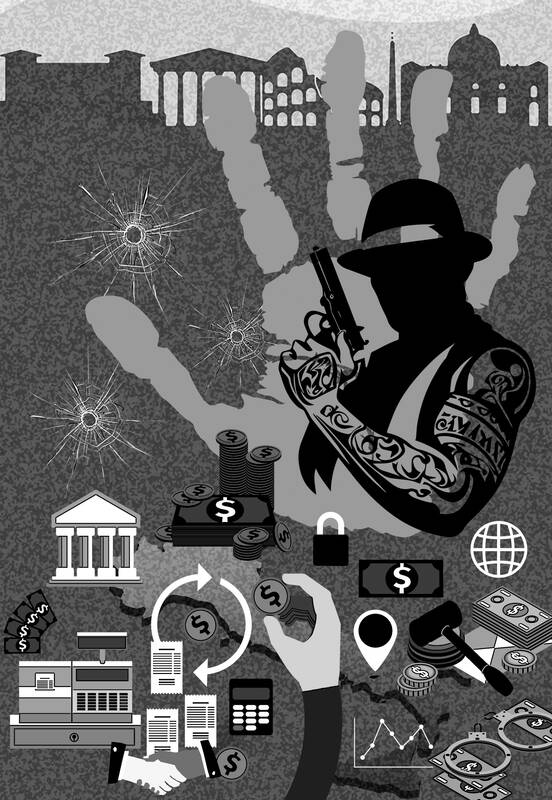

Illustration: Louise Ting

However, post-pandemic, there is a new trend developing that is a warning for all of Europe. While mobsters continue to follow the money in big cities, they are also feeding on increasing inequality and polarization to undermine the declining and indebted Italian state.

Italy’s traditional split of wealthy north and poor south is now being cut through with a new divide: between its biggest, most successful cities and the rest, Michele Riccardi, deputy director and senior researcher at Transcrime, a research institute in Milan, told me. In Sicily, this is translating into an economic revival of its picturesque tourist towns, where super wealthy people seeking to unlock Italy’s generous tax breaks in exchange for investments are buying up palatial apartments.

However, outside of these boom areas, there is “economic, social and cultural degradation,” Riccardi said.

That degradation, so visible in Palermo’s backstreets, provides the raw material for organized crime families and networks of Sicily’s Cosa Nostra to step into the breach.

A court case under way in Palermo provides an insight into how gangster tentacles are reaching more subtly, and pervasively, into the social and economic fabric. In the case, 31 business owners from a rundown southeastern area of Brancaccio in Palermo, a short stroll from the buzzy city center, are accused of aiding and abetting mobsters. The accused are on trial for denying having paid protection bribes to Cosa Nostra even though they have been caught on police wiretaps talking about having done so. Local prosecutors say the trial is so crucial, because — they allege — it is not fear that is stopping the business owners from admitting the payment of protection money, but complicity. In return, they get preferential deals on merchandise, legal services, loans or even social services.

False-invoicing services have become Cosa Nostra’s killer app, Riccardi said. If you are trying to cut costs to keep your business afloat in a more difficult economic environment, one way is to pay less taxes. That is where the fake invoices come in.

The process has become so widespread that “there is a tighter and tighter relationship between tax and financial crime,” he said. Undermining tax collection fuels a vicious circle, as less is available to be invested in already depressed communities, putting them further and further outside the lure to foreign investors and well-heeled tourists, and tying them more closely to the black economy. (Estimates of the size of Italy’s black economy vary widely — from about 10 percent to a third of GDP.)

It is not just a Sicilian phenomenon. I heard the same from Alessandra Dolci, one of Italy’s leading prosecutors against the mafia in Milan. She sees the same widening gulf between the inner city and periphery in Italy’s second city.

“To fight organized crime, we also need to fight the criminal economy of tax evasion,” Dolci said. She related the story of a mobster who told her he was making more money from his false-invoicing business than drug trafficking.

An added bonus, the mobster said, is that it was harder for law enforcement to track the paperwork than the narcotics, Dolci said.

Back in Palermo, Chief Prosecutor Maurizio De Lucia led the investigations that brought about the arrest of mafia boss Matteo Messina Denaro last year, after his 30 years on the run. A killer who boasted that his victims could “fill a cemetery,” Denaro was considered a godfather like something from a movie, a relic of Italy’s traditional mafia of atrocities and terrorism.

Today, mafia infiltration has become “a three-legged stool,” De Lucia said. It is more subtle, less violent and more economically stable. The three legs are the mob and its accomplices in politics and business. He too said that tax avoidance is becoming a major front in the battle against organized crime.

The dentist who does not issue an invoice has the same effect as the drug dealer, he said. “They are both using the same service, they are entering the same terrain.”

It is a reminder that the darker complexity of picturesque Sicilian idylls is not just the stuff of big budget fictional shows. It is real life, and it is more frightening for that too.

Rachel Sanderson is a contributor to Bloomberg Opinion. She was previously a columnist at the Financial Times.

US President Donald Trump’s second administration has gotten off to a fast start with a blizzard of initiatives focused on domestic commitments made during his campaign. His tariff-based approach to re-ordering global trade in a manner more favorable to the United States appears to be in its infancy, but the significant scale and scope are undeniable. That said, while China looms largest on the list of national security challenges, to date we have heard little from the administration, bar the 10 percent tariffs directed at China, on specific priorities vis-a-vis China. The Congressional hearings for President Trump’s cabinet have, so far,

US political scientist Francis Fukuyama, during an interview with the UK’s Times Radio, reacted to US President Donald Trump’s overturning of decades of US foreign policy by saying that “the chance for serious instability is very great.” That is something of an understatement. Fukuyama said that Trump’s apparent moves to expand US territory and that he “seems to be actively siding with” authoritarian states is concerning, not just for Europe, but also for Taiwan. He said that “if I were China I would see this as a golden opportunity” to annex Taiwan, and that every European country needs to think

For years, the use of insecure smart home appliances and other Internet-connected devices has resulted in personal data leaks. Many smart devices require users’ location, contact details or access to cameras and microphones to set up, which expose people’s personal information, but are unnecessary to use the product. As a result, data breaches and security incidents continue to emerge worldwide through smartphone apps, smart speakers, TVs, air fryers and robot vacuums. Last week, another major data breach was added to the list: Mars Hydro, a Chinese company that makes Internet of Things (IoT) devices such as LED grow lights and the

US President Donald Trump is an extremely stable genius. Within his first month of presidency, he proposed to annex Canada and take military action to control the Panama Canal, renamed the Gulf of Mexico, called Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy a dictator and blamed him for the Russian invasion. He has managed to offend many leaders on the planet Earth at warp speed. Demanding that Europe step up its own defense, the Trump administration has threatened to pull US troops from the continent. Accusing Taiwan of stealing the US’ semiconductor business, it intends to impose heavy tariffs on integrated circuit chips