Multilateralism is waning, and one of the world’s leading multilateral institutions, the WTO, is in crisis because the US has been blocking new appointments to its dispute settlement mechanism’s Appellate Body since 2018.

In the run-up to the WTO’s 13th Ministerial Conference last month, some optimists hoped to see progress on specific issues, such as an agreement not to impose tariffs on digital commerce, but expectations were generally low.

The pessimists were right. India led the charge against extending a moratorium on e-commerce tariffs, and only a last-minute deal prolonged it for another two years. After that, it is expected to expire.

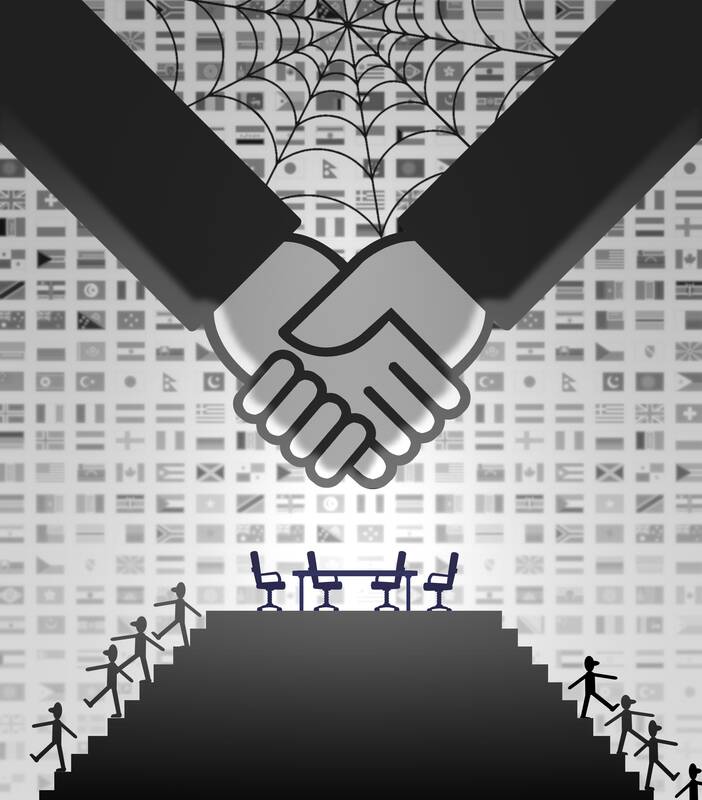

Illustration: Yusha

India and its allies celebrated the outcome as a victory. For the first time in years, the culprit undermining the WTO was not the US, but developing countries such as Indonesia, South Africa and Brazil.

True, what happened with digital commerce is characteristic of the usual conflicts that play out during trade negotiations. Free trade always produces winners and losers. Digital commerce might be in the interest of businesses in advanced economies, as well as consumers and businesses in low and middle-income countries. Users of an app, game or other software product made in a different country can pay lower prices in the absence of tariffs.

However, domestic producers reliably demand protection from imports, and governments see tariffs as a promising way to boost revenues.

While these issues are typical, developing countries’ opposition to an extended digital-tax moratorium is emblematic of a deeper problem: namely, the growing impression that the WTO has nothing to offer them anymore. The assumption is that it unilaterally serves the interests of big businesses rather than of the average person in a low or middle-income country.

Yet is this true?

Recent research shows that poverty reduction in the past three decades has been more likely in developing countries that are well integrated into the international trade system — as measured by the number of signed trade agreements and access to large, lucrative export markets. In this sense, the multilateral trade system has benefited the developing world.

International integration is particularly important for smaller economies. Unlike India and China, countries such as Thailand, Kenya and Rwanda cannot fall back on large domestic markets. No wonder opposition to trade deals so often comes from larger developing countries such as India, Indonesia and Brazil. They can afford to turn their back on international trade if the terms of the proposed deal are not enticing enough.

Yet even these countries appreciate the benefits of participation in global trade. For example, India used the closing of the Ministerial Conference to reaffirm its commitment to negotiation and multilateralism, in principle.

The question, then, is why developing countries have such a negative view of the WTO specifically.

Their dissatisfaction dates back to 1995, when the WTO succeeded the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

At the time, developing countries felt that they had just been pressured into signing a trade-related intellectual property rights agreement that would yield big payoffs for multinational corporations without offering many benefits to their own populations.

Another ongoing source of tension is agriculture, where developing countries traditionally have a comparative advantage. Existing trade agreements continue to permit high-income countries to subsidize local producers and impose tariffs on imports. Other rules, escape clauses and notification requirements have created de facto loopholes that only countries with abundant resources are able to exploit.

For example, fishing subsidies — another area of major contention — are permitted under certain conditions, but monitoring fishing stocks to prove that such conditions are being met is prohibitively expensive for most developing countries.

They therefore have good reason to complain that international trade rules are biased against them.

Looking ahead, a potentially bigger issue concerns advanced economies’ efforts to link trade agreements to labor and environmental standards, such as through the EU’s proposed Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. While well-intentioned, advanced economies must recognize that their efforts to address climate, labor and human-rights issues could have serious distributional consequences, potentially coming at the expense of many developing countries.

This is especially true of climate change. Low-income countries could have the most to lose from the consequences of climate change, but they are understandably reluctant to impede their own growth to fix a problem caused by richer countries’ past sins. Combine these concerns with high-income countries’ push toward “friend-shoring” — which implies more trade among rich countries, given the current geopolitical map — and today’s world starts to look even more like one where advanced economies are pitted against developing ones.

Ironically, the obvious way to avoid such division is to revive multilateralism. Now more than ever, challenges are global in nature and thus call for global solutions.

However, shared objectives, by definition, must account for the concerns of developing countries. That is what successful multilateralism has always demanded.

Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg, a former World Bank Group chief economist and editor-in-chief of the American Economic Review, is a professor of economics at Yale University.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

US President Donald Trump’s second administration has gotten off to a fast start with a blizzard of initiatives focused on domestic commitments made during his campaign. His tariff-based approach to re-ordering global trade in a manner more favorable to the United States appears to be in its infancy, but the significant scale and scope are undeniable. That said, while China looms largest on the list of national security challenges, to date we have heard little from the administration, bar the 10 percent tariffs directed at China, on specific priorities vis-a-vis China. The Congressional hearings for President Trump’s cabinet have, so far,

US political scientist Francis Fukuyama, during an interview with the UK’s Times Radio, reacted to US President Donald Trump’s overturning of decades of US foreign policy by saying that “the chance for serious instability is very great.” That is something of an understatement. Fukuyama said that Trump’s apparent moves to expand US territory and that he “seems to be actively siding with” authoritarian states is concerning, not just for Europe, but also for Taiwan. He said that “if I were China I would see this as a golden opportunity” to annex Taiwan, and that every European country needs to think

For years, the use of insecure smart home appliances and other Internet-connected devices has resulted in personal data leaks. Many smart devices require users’ location, contact details or access to cameras and microphones to set up, which expose people’s personal information, but are unnecessary to use the product. As a result, data breaches and security incidents continue to emerge worldwide through smartphone apps, smart speakers, TVs, air fryers and robot vacuums. Last week, another major data breach was added to the list: Mars Hydro, a Chinese company that makes Internet of Things (IoT) devices such as LED grow lights and the

US President Donald Trump is an extremely stable genius. Within his first month of presidency, he proposed to annex Canada and take military action to control the Panama Canal, renamed the Gulf of Mexico, called Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy a dictator and blamed him for the Russian invasion. He has managed to offend many leaders on the planet Earth at warp speed. Demanding that Europe step up its own defense, the Trump administration has threatened to pull US troops from the continent. Accusing Taiwan of stealing the US’ semiconductor business, it intends to impose heavy tariffs on integrated circuit chips