Harvard professor Ezra Vogel’s 1979 book Japan as Number One: Lessons for America became an instant bestseller in Japan. The flattering title certainly helped sales, but it was the book’s central argument — that the Japanese approach to governance and business were superior to others — that really made a splash.

At the time, Japan was riding high. Its GDP had grown by about 10 percent annually for most of the 1950s and 1960s, and 4 percent to 5 percent during the second half of the 1970s — a trend that would continue throughout the 1980s.

However, Japanese businessmen and political leaders were not sure whether Japan had succeeded economically because of its unique system or despite it. For them, Vogel’s book amounted to a kind of seal of approval and reinforced the belief that Japan could soon surpass the US to become the world’s largest economy.

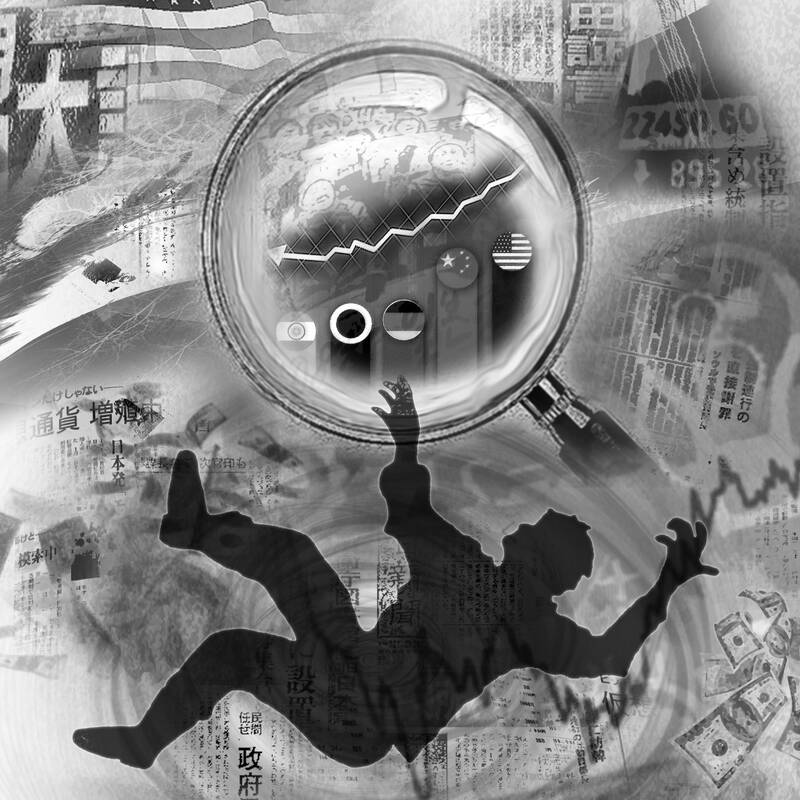

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

In the years that followed, Japan appeared to be progressing toward this goal. In the second half of the 1980s, Japanese stock prices tripled, and real asset prices rose fourfold. In 1988, Japan’s GDP amounted to 60 percent that of the US (in current dollars), and, with a population about half the size at the time, its GDP per capita was significantly higher. In 1995, following a sharp appreciation of the yen, Japan’s economy was about three-quarters the size of the US economy.

That turned out to be “peak” Japan. Soon, its economy was gripped by decades-long stagnation and deflation. From 1995 to 2010, Japan experienced negative GDP growth (in yen terms). Meanwhile, the US economy grew by about 2 percent annually, and China racked up year after year of double-digit growth. Today, Japan’s GDP amounts to just 15.4 percent that of the US, and China’s GDP has been larger than Japan’s since 2010. Far from rising to number one, Japan fell to number three.

The news that China had surpassed Japan as the world’s second-largest economy did not prompt much of an outcry from the Japanese public, which appeared practically resigned to their economy’s decline. To be sure, Japanese voters had handed the opposition Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) a victory over the long-dominant Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) the previous year.

However, the honeymoon with the DPJ did not last long. The party fell far short on governance, diplomacy and economic policy, and from 2009 to 2012, a parade of DPJ prime ministers each lasted barely a year in the position.

In the December 2012 election, Japanese voters tried a different approach, electing the LDP’s Shinzo Abe as prime minister for the second time. Abe quickly introduced a bold economic policy package — dubbed Abenomics — that aimed finally to lift the Japanese economy out of two decades of deflation and recession with three “arrows”: massive monetary easing, expansionary fiscal policy and a long-term growth strategy.

Abe’s plan worked — to a point. Thanks to the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) monetary expansion, Japan finally achieved a positive inflation rate.

However, real growth remained elusive, owing to rapid population aging. Though labor productivity increased significantly, the gains were insufficient to offset the decline in the number of workers and working hours. Add to that yen depreciation from 2012 to 2014, and Japan’s GDP declined (in US dollar terms), before flattening out.

Now, Japan has fallen even further: Last year, Germany surpassed Japan as the world’s third-largest economy. Once again, the public reaction to the news of Japan’s declining global position has amounted to a shrug. The kind of constructive anger that can spur dynamic reform is nowhere to be seen.

The list of measures needed to revitalize the Japanese economy is as well-known as it is long. For example, Japan must steer personal bank deposits and institutional savings to equities and alternatives. Productivity increases are sorely needed in every sector — an imperative that should be pursued through aggressive digitalization, given declining population size.

In the meantime, today’s labor shortages should drive up nominal wages, and strong demand for goods and services, as well as the rising costs of inputs, should be reflected in higher prices. This is something of a forgotten art in Japan: Over decades of deflation, as consumers turned on companies that raised prices, the price mechanism became practically nonoperational. Relative and absolute prices froze and resource allocation suffered.

The good news is that “deflationary mindsets” are changing, not least because the BOJ has managed to keep inflation above its 2 percent target for about two years.

However, ultra-accommodative monetary policy carries high costs. The growing interest-rate differential with the US, where rates rose rapidly in 2022 and last year, contributed to the yen’s rapid depreciation against the dollar, from ¥115 in January 2022 to ¥150 ten months later and throughout last year.

However, while the yen’s depreciation compared with the US dollar might have contributed to Japan’s declining GDP in US dollars, it is not the whole story. After all, a weak currency can often boost growth by making exports more competitive.

However, there is no sign of this in Japan, which reflects a deeper problem: Both innovation and production have largely left the country. Payments to US information technology (IT) service companies are rising fast, pushing imports higher. Japan must take urgent and decisive steps to reverse this trend, such as by promoting science and technology education to generate IT-service production domestically.

If the economy’s fall to number four is not enough to wake Japan up, it is soon to fall to number five. The IMF projects that India’s GDP would overtake Japan’s (in dollar terms) in 2026. To stave off further decline, the Japanese government must devise a clear strategy for raising productivity, expanding the workforce and allocating scarce labor to the most productive sectors.

Takatoshi Ito, a former Japanese deputy vice minister of finance, is a professor in the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and a senior professor in the Japanese National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies in Tokyo.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its