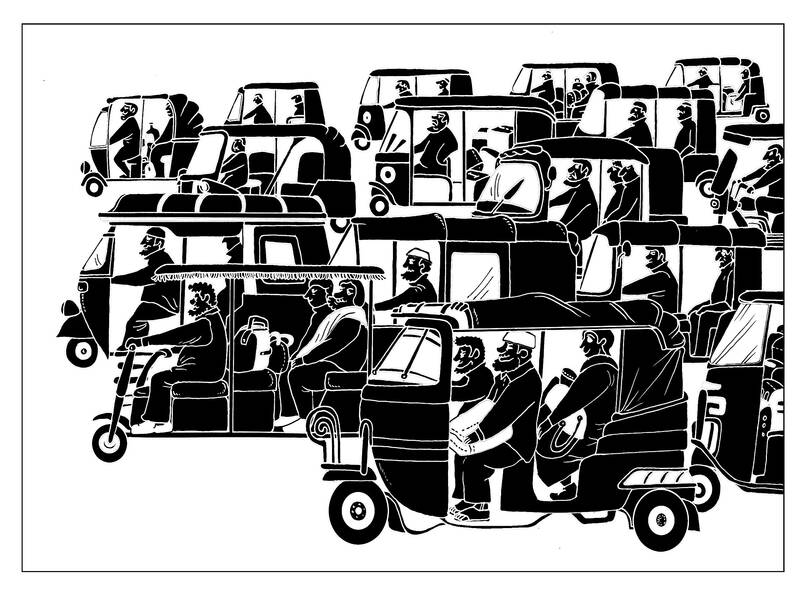

Life moves pretty fast. That is especially true in India’s booming cities.

A decade ago, the country’s iconic auto-rickshaws had three wheels and a diesel engine. Battery-powered versions existed, but only enough to be seen as a novelty and unregulated threat. Officially, only 12 e-rickshaws were sold nationwide in 2014 (The true number would be higher, but the unregulated nature of the industry meant that most sales were not captured in official statistics).

How far we have come. The place where road transport is shifting most rapidly to battery power is not Oslo or Shenzhen, but Delhi. E-rickshaws took a 54 percent share of India’s three-wheeler market last year, driven by zippy, longer-range models and running costs that are a fraction of petroleum-powered alternatives. Visiting the country last week, one of the first stops for Uber Technologies Inc chief executive officer Dara Khosrowshahi was to get behind the wheel of a Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd electric three-wheeler and promise an expansion into two and three-wheeled ride-hailing.

Illustration: Mountain People

Those betting India would come to the rescue of flailing global oil demand (it is reckoned to be the biggest source of consumption growth between now and 2030, outstripping even China) need to reckon with how things are changing on the streets.

There is no mystery why e-rickshaws have been taking over. Buy a Bajaj Maxima with an engine and you would pay about 3 rupees (US$0.04) per kilometer for diesel — a significant slice of earnings that average out about 10 rupees per kilometer. A Piaggio Ape E City with a lithium-ion battery charged at home, on the other hand, might cost just 0.27 rupees per kilometer. As a result, e-rickshaws are not just cleaner and quieter, they are more profitable, too. That is a decisive consideration for drivers who are usually rural migrants trying to get a foothold in the big city.

If this revolution was confined only to three-wheelers, it would not be much to get excited about. Auto-rickshaws are a highly distinctive part of India’s road fleet, but not a very significant one. Trucks and cars are sold in far greater numbers, while more than 70 percent of vehicle sales are two-wheeled scooters and motorbikes.

However, the hard financial logic that has caused e-rickshaws to take over is starting to play out on two wheels, too. Manufacturers are launching a slew of new models with price tags and performance to compete with conventional bikes and scooters that retail for less than 100,000 rupees. With gasoline prices up about a third thanks to the rise in crude since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, that could spark a stampede like the one that transformed the e-rickshaw market. Only about 5 percent of two-wheelers sold last year were battery-powered. McKinsey & Co forecasts that figure would hit 60 percent to 70 percent by 2030.

“The industry is going through a price war,” Hero MotoCorp Ltd emerging mobility unit head Swadesh Srivastava told an investor call on Feb. 10.

Hero’s main domestic two-wheeler rival, TVS Motor Co, plans to offer models this year in every segment of the market, from premium to basic, and to expand its dealership network from 400 cities to 800 over the three months through March.

That could start to cause real pain for oil producers who have mostly shrugged off the e-rickshaw revolution. Only about 1.4 percent of India’s gasoline and diesel is consumed by three-wheelers, but two-wheelers gulp down about 17 percent of the total. The International Energy Agency’s latest estimates for the country’s oil demand are already being trimmed. Its latest report reckons 6.6 million barrels a day would be consumed in 2030 — above 5.5 million barrels last year, but well down from a central forecast of 6.8 million daily barrels in its global outlook on October last year.

However, the real prize lies beyond two wheels. The biggest polluters by far on India’s roads are not two or three-wheelers but trucks, which consume nearly half of all gasoline and diesel. Trucks are normally seen as the hardest segment for electric vehicles (EV) to crack. The biggest rigs are simply too energy-hungry to be powered by a battery. Even smaller ones are worked hard day and night for thin margins, making it difficult to spare the time to charge up their power packs.

Even here the sands are shifting. Tata Motors Ltd launched its first small electric truck in 2022 while Mahindra, the leading e-rickshaw producer, is planning to release a range next year. Truck owners, like rickshaw drivers, are intensely sensitive to the combined costs of purchase, refueling and maintenance — and manufacturers seem on the cusp of hitting their sweet spot.

Current e-trucks work out cheaper than diesel models once you have been operating them for five to seven years, Ashok Leyland Ltd managing director Shenu Agarwal on Feb. 6 told investors.

“If we can bring it down below five years, then it will start making much more sense,” he said.

In the US and Europe, the shift to EV was a top-down affair, best exemplified by Elon Musk’s 2006 promise to start by building an electric sports car and then use the profits to make progressively more affordable mass-market vehicles. Well-heeled drivers cannot get enough of luxury EVs like Porsche AG’s Taycan and Rolls-Royce’s Spectre, while the rest of us are waiting in vain for the sub-US$30,000 city cars we were promised.

India seems to be moving in the opposite direction. Electrification of conventional cars and SUVs is still moving at a snail’s pace, with battery cars winning just a 2 percent share of four-wheelers last year. That does not matter much in a market that is dominated by smaller vehicles and cost-conscious drivers. When the EV revolution arrives in India, it would come from the bottom up.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. Previously, he worked for Bloomberg News, the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

US President Donald Trump is systematically dismantling the network of multilateral institutions, organizations and agreements that have helped prevent a third world war for more than 70 years. Yet many governments are twisting themselves into knots trying to downplay his actions, insisting that things are not as they seem and that even if they are, confronting the menace in the White House simply is not an option. Disagreement must be carefully disguised to avoid provoking his wrath. For the British political establishment, the convenient excuse is the need to preserve the UK’s “special relationship” with the US. Following their White House

Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention. If it makes headlines, it is because China wants to invade. Yet, those who find their way here by some twist of fate often fall in love. If you ask them why, some cite numbers showing it is one of the freest and safest countries in the world. Others talk about something harder to name: The quiet order of queues, the shared umbrellas for anyone caught in the rain, the way people stand so elderly riders can sit, the

After the coup in Burma in 2021, the country’s decades-long armed conflict escalated into a full-scale war. On one side was the Burmese army; large, well-equipped, and funded by China, supported with weapons, including airplanes and helicopters from China and Russia. On the other side were the pro-democracy forces, composed of countless small ethnic resistance armies. The military junta cut off electricity, phone and cell service, and the Internet in most of the country, leaving resistance forces isolated from the outside world and making it difficult for the various armies to coordinate with one another. Despite being severely outnumbered and

After the confrontation between US President Donald Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy on Friday last week, John Bolton, Trump’s former national security adviser, discussed this shocking event in an interview. Describing it as a disaster “not only for Ukraine, but also for the US,” Bolton added: “If I were in Taiwan, I would be very worried right now.” Indeed, Taiwanese have been observing — and discussing — this jarring clash as a foreboding signal. Pro-China commentators largely view it as further evidence that the US is an unreliable ally and that Taiwan would be better off integrating more deeply into