The jeans and the hairstyles are back, and so is some of the music. The 1990s have become so much of a part of Gen Z’s conversations that there is an entire collection of hashtags and accounts referencing that era, from @90sanxiety to #Y2K.

Still, one aspect of 1990s history is particularly troubling: This generation’s affection — particularly in Asia — for strongmen politicians, fueled in part by social media strategies that have helped to erase their pasts and remake their image for an entertainment-and-meme hungry youth.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in Indonesia — which has just held a watershed election — and in the Philippines presidential poll in 2022. Both contests saw strongmen politicians harking from a previous time winning; Prabowo Subianto, Indonesia’s president-elect, is a former general from the dictator Suharto’s era. In Manila, Ferdinand Marcos Jr, son of the former autocrat Ferdinand Marcos, put his clan back into Malacanang Palace 36 years after his father fled the country.

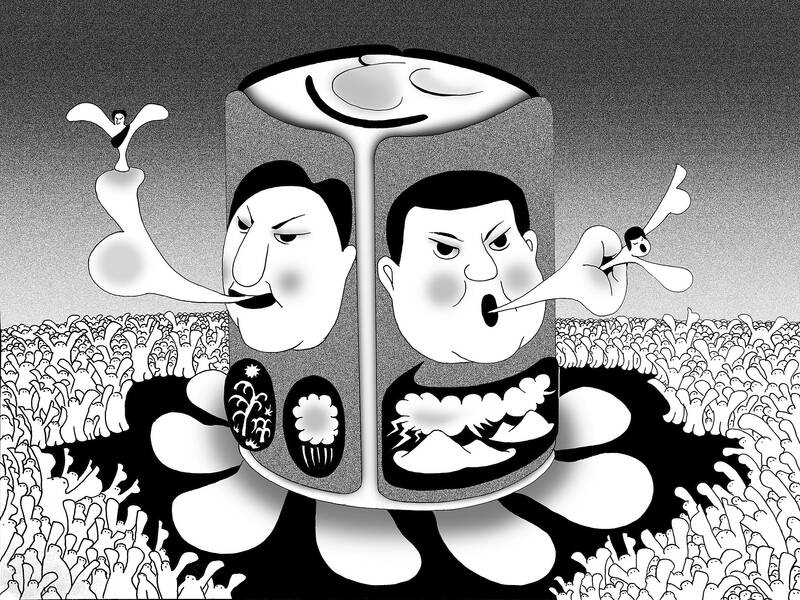

Illustration: Mountain People

The 1990s in parts of Asia was an epoch of strongmen, characterized by economic stability, but also authoritarian rule. In Indonesia, the nation that I call home, that meant regularly receiving copies of news magazines with huge swathes of text blacked out, the offending words about Suharto erased so no one could read or be influenced by them. Books of literary giants like Pramoedya Ananta Toer were banned, among scores of novels and other writing by authors linked to what the regime saw as leftist groups. These included social science texts, historical studies, literary works and memoirs.

This led to an effective erasure of the past from the minds of Indonesians of that time.

Control the narrative and you control the people.

A similar phenomenon is happening now, but this time through the use of social media and in an environment where young people might have access to information, but perhaps not the desire to consume or understand it.

“I am disappointed with our younger generation,” Harkristuti Harkrisnowo, professor of law at the University of Indonesia, told me. “They see this presidential election as just another entertaining event, rather than a way to decide what kind of country they will live in.”

The election campaign was pretty entertaining, particularly the events that Prabowo and his vice presidential candidate, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, the eldest son of Indonesian President Joko Widodo, held for the masses. Giant cartoon balloons of their images were strewn across stadium grounds and families took photographs near life-sized images of them, dancing along to the catchy tune that became their anthem.

People I met at the rallies were quick to dismiss decades-old allegations of human rights violations against Prabowo, telling me they were focused on the future, not the past.

It was the same rhetoric I heard in the Philippines in May 2022 during the country’s presidential elections.

One woman said she was convinced that Bongbong Marcos would bring back the gold stolen by his father, because she had seen a video about it on YouTube.

Another family in one of Manila’s many slums was convinced that jobs would be aplenty, because the Marcoses “know money is important.”

This social media bonanza rewrote history about the dictatorship and painted it as a golden era, which helped his campaign — although he denied any connection to the posts.

Never mind that his father’s regime saw thousands killed, tortured or disappeared under martial law. The Internet had rebranded Marcos Jr. and for Filipinos, he was the right man for the job.

Rumors were aplenty that the same PR team that had helped Marcos Jr repeated its success with Prabowo. These could not be verified. At the time of writing, neither camp had responded to questions about to the speculation.

If true, the strategy has worked. Recent research published by the institute also looked at the appeal of the take-charge image in Prabowo’s victory. About 54 percent of respondents who liked him did so because of his “strongman” image, the data showed, highlighting attributes like firm, authoritative, tough and disciplined. They were seemingly unfazed about the possibility of an authoritarian running the country.

That is because the majority of the people voting in Indonesia do not remember the 1990s, said Michael Vatikiotis, a longtime Southeast Asia observer and author of Blood & Silk: Power & Conflict in Modern Southeast Asia.

“It’s about continuity for the youth, a message of positivity,” he said. “They want socioeconomic stability and they believe that the Prabowo-Gibran team can give it to them.”

It is true that, in Indonesia at least, the 1990s were characterized by a strong economic growth rate — only to see that destroyed by mismanagement, corruption, debt and the Asian financial crisis.

Bring back the fashion, the music, even Jennifer Aniston’s haircut, but some things from the 1990s should stay right where they are — in the history books.

Karishma Vaswani is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asia politics with a special focus on China. Previously, she was the BBC’s lead Asia presenter and worked for the BBC across Asia and South Asia for two decades.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its