In October last year, the US Trade Representative (USTR) abandoned its longstanding demand for WTO provisions to protect cross-border data flows, prevent forced data localization, safeguard source codes and prohibit countries from discriminating against digital products based on nationality. It was a shocking shift: one that jeopardizes the very survival of the open Internet, with all the knowledge-sharing, global collaboration and cross-border commerce that it enables.

The USTR says that the change was necessary because of a mistaken belief that trade provisions could hinder the ability of the US Congress to respond to calls for regulation of Big Tech firms and artificial intelligence.

However, trade agreements already include exceptions for legitimate public-policy concerns, and the US Congress itself has produced research showing that trade deals cannot impede its policy aspirations. Simply put, the US — as with other countries involved in WTO deals — could regulate its digital sector without abandoning its critical role as a champion of the open Internet.

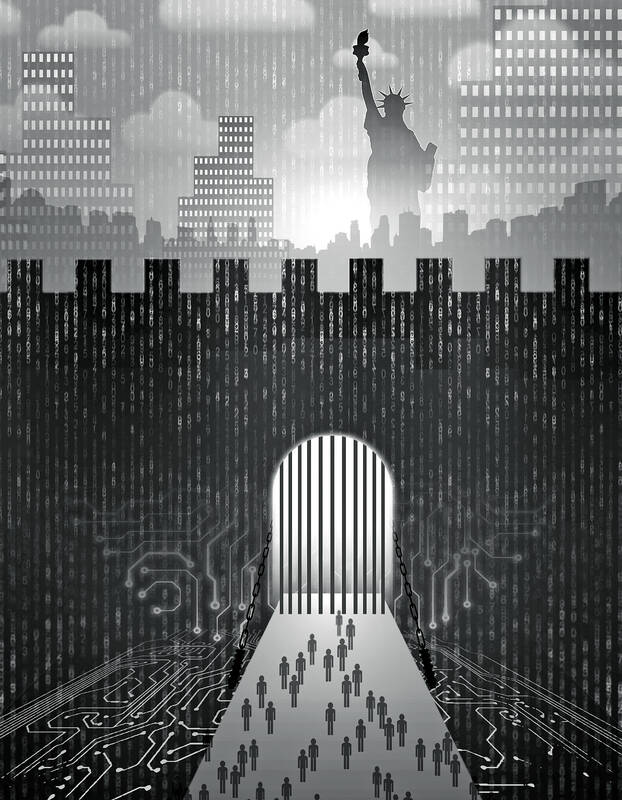

Illustration: Yusha

The potential consequences of the US’ policy shift are as far-reaching as they are dangerous. Fear of damaging trade ties with the US has long deterred other actors from imposing national borders on the Internet. Now, those who have heard the siren song of supposed “digital sovereignty” as a means to ensure their laws are obeyed in the digital realm have less reason to resist it. The more digital walls come up, the less the walled-off portions resemble the Internet.

Several countries are already trying to replicate China’s heavy-handed approach to data governance. Rwanda’s data protection law, for instance, forces companies to store data within its borders unless otherwise permitted by its cybersecurity regulator — making personal data vulnerable to authorities known to use data from private messages to prosecute dissidents.

At the same time, a growing number of democratic countries are considering regulations that, without strong safeguards for cross-border data flows, could have a similar effect of disrupting access to a truly open Internet.

Without a strong commitment on crucial Internet protections from the US and the 90 WTO members involved in the joint e-commerce initiative, there is a real risk that many more countries — including the more than 100 developing countries without an approach to data governance — could be swayed to choose a regulatory path that veers away from an open Internet.

As more barriers to information flows are erected, the risk of harm to people, businesses and countries rises. Consider data-localization mandates, which might require all information about citizens or residents to be stored, collected or processed within their country’s physical borders. Far from protecting individual privacy and security, such mandates compromise it.

For starters, the mandates could leave data more vulnerable to direct seizure by authorities that do not respect human rights. Over the past decade, the Wikimedia Foundation — the nonprofit that hosts Wikipedia, the free online encyclopedia created and maintained by volunteer editors around the world — has received dozens of requests for user data each year, many of which have had little or no legal basis.

There have been cases, for example, where a government or wealthy individual has sought to obscure accurate public information or even to take retaliatory action against the volunteer who published it. The Wikimedia Foundation refuses such requests, but data-localization requirements could make this more difficult, as governments assume greater control over information stored within their borders.

Then there are the economic implications. Establishing data-collection and storage facilities in countries around the world would be expensive — so expensive that it could threaten the economic viability of non-profit and commercial entities alike. Smaller players would have an even harder time competing with big global tech platforms.

Finally, forcing Internet-based services to establish multiple, redundant data centers in different countries would create new security vulnerabilities, which leave sensitive personal and corporate information in greater danger of intrusions and data breaches. People’s access to information could also be hampered.

Following the US announcement in October last year, G7 ministers were quick to reaffirm their commitment to open digital trade and digital markets, and their support for the Data Free Flow with Trust initiative, which promotes coordinated approaches to privacy and data governance amid increasing digital protectionism. However, the G7, on its own, is ill-equipped to counter the misguided policies and geopolitically-driven efforts that could carve up the Internet beyond recognition. To preserve an open, globally-connected and secure Internet, all countries — including the US, with its enduring global clout — must reassert strong support for the policies that underpin it.

However, the sustained effort needed to prevent the global erosion of the Internet goes beyond trade negotiations. People everywhere must urge their leaders to protect the Internet from aggressive digital-sovereignty measures at the WTO’s joint initiative on e-commerce negotiations, in other international engagements and at home. For their part, policymakers making decisions or designing legislation must be diligent in assessing potential impacts on online data flows and prevent harm to Internet openness.

In some ways, the Internet is a victim of its own success: it has become so integral to our lives that we take it for granted. However, the survival of the Internet as we know it today is far from guaranteed. Only with a concerted global effort could we ensure that it does not become increasingly fragmented, insecure and under the control of governments and corporations.

Natalie Dunleavy Campbell is senior director of North American Government and Regulatory Affairs at the Internet Society. Stan Adams is lead public policy specialist for North America at the Wikimedia Foundation.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2024.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion