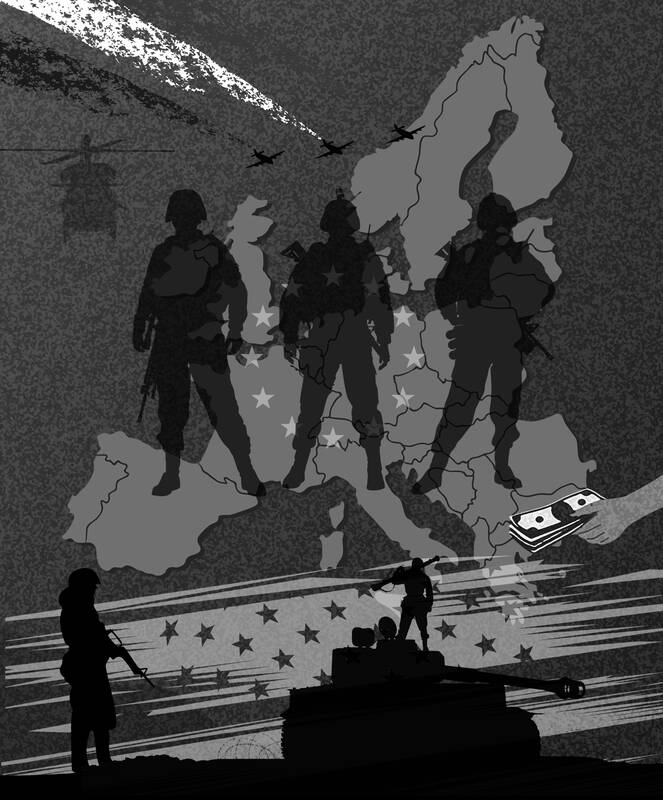

Europe is in a race against time to arm itself. Senior officials know they should not be counting on the US for Europe’s defense, but building up their own military capabilities requires a determination they are yet to prove.

The continent’s efforts leave it at least a decade away from being able to defend itself unaided, officials familiar with these preparations said.

Amid fears that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine might represent just the first phase of much broader imperial ambitions, Western intelligence assessments are suggesting that the Kremlin could be in a position to target a NATO member within the much shorter span of three to five years.

Illustration: Louise Ting

The resurgence of former US president Donald Trump has increased the pressure, after the presidential hopeful said he would welcome a Russian attack on NATO allies falling short on their spending commitments. That would leave more than a third of the alliance outside of the US security umbrella, new figures released on Wednesday show.

The fact is that European leaders need no encouragement from across the pond to turn themselves into a serious military power, but everything from supply chain snags to disagreements over procurement means they are falling short.

“It all takes time,” Estonian Minister of Defense Hanno Pevkur said in an interview in Brussels on Jan. 30. “Unfortunately, we do not have time.”

Europe is witnessing the biggest conflict on its soil since World War II and feels threatened. It has a long history of relying on the US so it feels unprepared, and because Trump narrowly outpolls his democratic rival in surveys for the November election, it is feeling increasingly rattled, said officials who spoke to Bloomberg and who asked to remain anonymous when discussing matters of strategy.

These fears were likely to dominate panels and conversations at this weekend’s annual Munich Security Conference, a gathering of leaders, military officials and security experts, which ends today, days before the two-year mark of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Trump’s provocative weekend remarks were just the latest combative statements reminding European leaders how, at a time when they are battling unpredictable foes, they now contend with unpredictable allies, too.

The specter of his return to the White House has heightened the stakes. However, they are already foregrounded under what is superficially a more cozy transatlantic partnership with US President Joe Biden, who has struggled to push through the military aid Ukraine badly needs to repel its Russian invaders.

The US’ NATO partners arrested a long-term trend by increasing defense expenditure every year since Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, and in no single year so steeply as just after its second invasion. However, that has been insufficient to rival US largesse — still less to fill the breach were it to retreat.

If European nations came under attack today, they would still be dependent on the US for a slew of capabilities, and the gaps are especially large in certain areas. These include air and missile defense, deep-fire missiles, and the advanced computer systems needed to conduct warfare, officials familiar with the matter said.

The worst-case scenario would emerge from three things happening in succession: Europe not acting quickly enough to invest in its defense, the US failing to send Ukraine more aid, and Trump winning re-election then pulling the US out of NATO, one senior EU diplomat said.

Since only the last of these is an outside prospect, it is not hard to see why the moment has European officials on edge.

Several told Bloomberg they suspect Trump wants to spook the continent into spending more, rather than withdraw from the alliance entirely. The risk he makes good on such threats has been mollified by a new bill that bars a president from withdrawing unilaterally. The fear that he would summarily cut off aid for Kyiv and hand Moscow a victory is far more imminent to them.

Trump has long given allies reasons to doubt his commitment to Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, which enjoins every NATO member to support others under attack. The only time it has ever been invoked was after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the US.

More than US$60 billion worth of aid to Ukraine is stalled in Congress, exacerbating European suspicions over the US’ commitment to their security. The outbreak of conflict in the Middle East has also reminded Europe of Washington’s split attentions, and they fear forces could ultimately be transferred elsewhere, including to Asia, if China were ever to attack Taiwan.

One way that Europe is trying to keep the US on its side is by emphasizing, behind the scenes, that it is attuned to its concerns over China. That could serve as a reminder to the US public of NATO’s relevance to the US.

If Russia wins in Ukraine, and if the US disengages — either prior to that or consequently — the EU’s main powers would need to do more than just make up the existing shortfall to defend the alliance’s eastern flank. NATO’s presence would have to triple along its new border with an emboldened Russian President Vladimir Putin, another senior EU diplomat said.

After the end of the Cold War, European countries slashed defense budgets and divested large equipment in the belief that the continent’s major wars were a thing of the past.

Fast forward to this year and 18 NATO allies are on course to reach the alliance-wide goal of spending 2 percent of GDP, compared with just three of them in 2014 — one of which was the US. The effects would take time to be felt, since they are trying to churn out ammunition and weapons at a time when demand is skyrocketing around the world, leading to competition for both components and raw materials.

Compared with last year, the EU expects to triple its production of artillery shells to about 1.4 million units this year. The problem is that Russia is ramping up faster than expected and would make 4 million units this year, Estonian estimates showed.

The US has about 80,000 forces stationed across Europe, hosts missile defense sites in Poland and Romania and four destroyer warships in Spain. It leads a battle group and contributes forces to others on the eastern flank. Crucially, it also stores about 100 tactical nuclear weapons in five NATO nations: Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Turkey.

While France and the UK have nuclear weapons, these would not be enough to deter Russia from using one of its own, former US Army Europe commander and retired lieutenant general Ben Hodges said.

“The US provides a nuclear umbrella and it’s because of that the Russians would never dare to attack a NATO country,” Hodges said.

NATO and European allies are working to give their weapons greater interoperability, given the many different types of weapons systems in use across Europe, which hampers forces’ ability to fight side by side.

The challenge was laid bare when Ukrainian fighters tried — and failed — to use the same caliber ammunition in similar equipment donated by different Western allies.

In trying to build up military capability, Europe is derailed by an almost Trump-like concern: that of protectionism. Clashes between Paris and Berlin over whether to buy foreign weapons systems are inciting tensions at a time when joint procurement could be growing capacity.

France has held back from joining a German-led anti-missile program, dubbed the European Sky Shield, which would purchase air defense systems from abroad, including the Israeli Arrow 3 and US-made Patriot.

The concern in Paris is that buying outside of the EU displaces investment that would otherwise go toward boosting local industry, especially as big weapons purchases involve long contracts and years of maintenance.

“We all agree there’s been fragmentation in Europe, because we all have this reflex of doing everything by ourselves,” Dutch Minister of Defense Kajsa Ollongren said in an interview on Jan. 31. “Now we have to have a European reflex, and that will make all of us stronger.”

Grouping orders among different member states would help solve interoperability problems and drive production by giving defense contractors clarity about demand. Large multinational orders are already taking place, including through NATO’s procurement agency and the European Defense Agency.

In the coming weeks, European Commissioner for the Internal Market Thierry Breton is due to unveil an EU defense strategy that would designate strategic areas for investment and strip away red tape for businesses, among other measures.

At an event last month he pointed to Trump as he urged Europe to do “drastically” more to boost its own defense.

“Now more than ever, we know that we are on our own,” he said.

With assistance from Cagan Koc, Alan Katz, Ania Nussbaum, Alberto Nardelli and Ben Sills.

Why is Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) not a “happy camper” these days regarding Taiwan? Taiwanese have not become more “CCP friendly” in response to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) use of spies and graft by the United Front Work Department, intimidation conducted by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the Armed Police/Coast Guard, and endless subversive political warfare measures, including cyber-attacks, economic coercion, and diplomatic isolation. The percentage of Taiwanese that prefer the status quo or prefer moving towards independence continues to rise — 76 percent as of December last year. According to National Chengchi University (NCCU) polling, the Taiwanese

US President Donald Trump is systematically dismantling the network of multilateral institutions, organizations and agreements that have helped prevent a third world war for more than 70 years. Yet many governments are twisting themselves into knots trying to downplay his actions, insisting that things are not as they seem and that even if they are, confronting the menace in the White House simply is not an option. Disagreement must be carefully disguised to avoid provoking his wrath. For the British political establishment, the convenient excuse is the need to preserve the UK’s “special relationship” with the US. Following their White House

It would be absurd to claim to see a silver lining behind every US President Donald Trump cloud. Those clouds are too many, too dark and too dangerous. All the same, viewed from a domestic political perspective, there is a clear emerging UK upside to Trump’s efforts at crashing the post-Cold War order. It might even get a boost from Thursday’s Washington visit by British Prime Minister Keir Starmer. In July last year, when Starmer became prime minister, the Labour Party was rigidly on the defensive about Europe. Brexit was seen as an electorally unstable issue for a party whose priority

US President Donald Trump’s return to the White House has brought renewed scrutiny to the Taiwan-US semiconductor relationship with his claim that Taiwan “stole” the US chip business and threats of 100 percent tariffs on foreign-made processors. For Taiwanese and industry leaders, understanding those developments in their full context is crucial while maintaining a clear vision of Taiwan’s role in the global technology ecosystem. The assertion that Taiwan “stole” the US’ semiconductor industry fundamentally misunderstands the evolution of global technology manufacturing. Over the past four decades, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, led by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), has grown through legitimate means