What does it take to change a person’s mind? As generative artificial intelligence (AI) becomes more embedded in customer-facing systems — think of human-like phone calls or online chatbots — it is an ethical question that needs to be addressed widely.

The capacity to change minds through reasoned discourse is at the heart of democracy. Clear and effective communication forms the foundation of deliberation and persuasion, which are essential to resolve competing interests. However, there is a dark side to persuasion: false motives, lies and cognitive manipulation — malicious behavior that AI could facilitate.

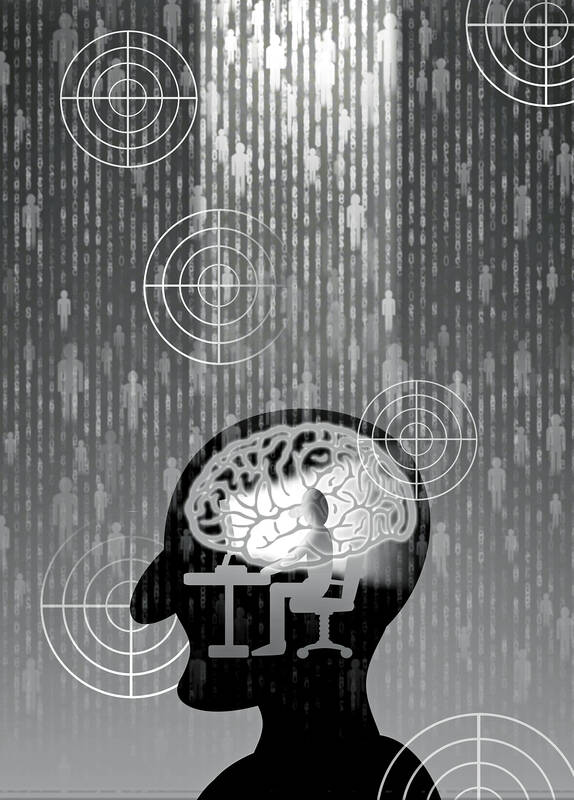

In the not-so-distant future, generative AI could enable the creation of new user interfaces that could persuade on behalf of any person or entity with the means to establish such a system. Leveraging private knowledge bases, these specialized models would offer different truths that compete based on their ability to generate convincing responses for a target group — an AI for each ideology. A wave of AI-assisted social engineering would surely follow, with escalating competition making it easier and cheaper for bad actors to spread disinformation and perpetrate scams.

Illustration: Yusha

The emergence of generative AI has thus fueled a crisis of epistemic insecurity. The initial policy response has been to ensure that humans know that they are engaging with an AI. In June, the European Commission urged large tech companies to start labeling text, video and audio created or manipulated by AI tools, while the European Parliament is pushing for a similar rule in the forthcoming AI Act. This awareness, the argument goes, would prevent us from being misled by an artificial agent, no matter how convincing.

However, alerting people to the presence of AI would not necessarily safeguard them against manipulation. As far back as the 1960s, the ELIZA chatbot experiment at MIT demonstrated that people could form emotional connections with, have empathy for, and attribute human thought processes to a computer program with anthropomorphic characteristics — in this case, natural speech patterns — despite being told that it is a non-human entity.

We tend to develop a strong emotional attachment to our beliefs, which then hinders our ability to assess contradictory evidence objectively. Moreover, we often seek information that supports, rather than challenges, our views. Our goal should be to engage in reflective persuasion, whereby we present arguments and carefully consider our beliefs and values to reach well-founded agreements or disagreements.

However, crucially, forming emotional connections with others could increase our susceptibility to manipulation, and we know that humans could make these types of connections even with chatbots that are not designed to do so. When chatbots are built to connect emotionally with humans, this would create a new dynamic rooted in two longstanding problems of human discourse: asymmetrical risk and reciprocity.

Imagine that a tech company creates a persuasive chatbot. Such an agent would be taking essentially zero risk — either emotional or physical — in attempting to convince others. As for reciprocity, there is very little chance that the chatbot doing the persuading would have any capacity to be persuaded. It is more likely that an individual could get the chatbot to concede a point in the context of their limited interaction, which would then be internalized for training. This would make active persuasion — which is about inducing a change in belief, not reaching momentary agreement — largely infeasible.

In short, we are woefully unprepared for the dissemination of persuasive AI systems. Many industry leaders, including OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, have raised awareness about its potential threat. However, awareness does not translate into a comprehensive risk-management framework.

A society cannot be effectively inoculated against persuasive AI, as that would require making each person immune to such agents — an impossible task. Moreover, any attempt to control and label AI interfaces would result in individuals transferring inputs to new domains, not unlike copying text produced by ChatGPT and pasting it into an email. System owners would therefore be responsible for tracking user activity and evaluating conversions.

However, persuasive AI need not be generative in nature. A wide range of organizations, individuals and entities have already bolstered their persuasive capabilities to achieve their objectives. Consider state actors’ use of computational propaganda, which involves manipulating information and public opinion to further national interests and agendas.

Meanwhile, the evolution of computational persuasion has provided the advertising-technology industry with a lucrative business model. This burgeoning field not only demonstrates the power of persuasive technologies to shape consumer behavior, but also underscores the significant role they could play in driving sales and achieving commercial objectives.

What unites these diverse actors is a desire to enhance their persuasive capacities. This mirrors the ever-expanding landscape of technology-driven influence, with all its known and unknown social, political, and economic implications. As persuasion is automated, a comprehensive ethical and regulatory framework becomes imperative.

Mark Esposito is a professor at Hult International Business School and a co-author of The Great Remobilization: Strategies and Designs for a Smarter Global Future. Josh Entsminger is a PhD student in innovation and public policy at the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose. Terence Tse is a professor at Hult International Business School and a co-author of The Great Remobilization: Strategies and Designs for a Smarter Global Future.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention. If it makes headlines, it is because China wants to invade. Yet, those who find their way here by some twist of fate often fall in love. If you ask them why, some cite numbers showing it is one of the freest and safest countries in the world. Others talk about something harder to name: The quiet order of queues, the shared umbrellas for anyone caught in the rain, the way people stand so elderly riders can sit, the

Taiwan’s fall would be “a disaster for American interests,” US President Donald Trump’s nominee for undersecretary of defense for policy Elbridge Colby said at his Senate confirmation hearing on Tuesday last week, as he warned of the “dramatic deterioration of military balance” in the western Pacific. The Republic of China (Taiwan) is indeed facing a unique and acute threat from the Chinese Communist Party’s rising military adventurism, which is why Taiwan has been bolstering its defenses. As US Senator Tom Cotton rightly pointed out in the same hearing, “[although] Taiwan’s defense spending is still inadequate ... [it] has been trending upwards

Small and medium enterprises make up the backbone of Taiwan’s economy, yet large corporations such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) play a crucial role in shaping its industrial structure, economic development and global standing. The company reported a record net profit of NT$374.68 billion (US$11.41 billion) for the fourth quarter last year, a 57 percent year-on-year increase, with revenue reaching NT$868.46 billion, a 39 percent increase. Taiwan’s GDP last year was about NT$24.62 trillion, according to the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, meaning TSMC’s quarterly revenue alone accounted for about 3.5 percent of Taiwan’s GDP last year, with the company’s

In an eloquently written piece published on Sunday, French-Taiwanese education and policy consultant Ninon Godefroy presents an interesting take on the Taiwanese character, as viewed from the eyes of an — at least partial — outsider. She muses that the non-assuming and quiet efficiency of a particularly Taiwanese approach to life and work is behind the global success stories of two very different Taiwanese institutions: Din Tai Fung and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC). Godefroy said that it is this “humble” approach that endears the nation to visitors, over and above any big ticket attractions that other countries may have