For a long moment, Japan feared the worst. After the magnitude 7.5 earthquake that struck on New Year’s Day, authorities announced the most serious tsunami alert issued since the 2011 disaster that devastated the Tohoku region. Waves of up to 5m were feared. The temblor caused tremors on the highest level on Japan’s Shindo shaking scale for only the seventh time on record. A major calamity felt imminent.

The Noto region has indeed experienced a devastating blow. At the time of writing, at least 77 are confirmed dead; more could follow as authorities reach houses that have been flattened or burned. However, the greatest fears in the immediate aftermath have not yet been realized — with both the 2011 and the 2016 Kumamoto quakes having been preceded by strong foreshocks, further catastrophe could strike.

Many I spoke to were surprised by the level of urgency in the warnings given just after the quake hit. An announcer on Japan’s public broadcaster NHK, in a tone of practiced panic, implored viewers to “Stop looking at the TV and run, now,” while graphics warned, in both Japanese and English, in the simplest terms: “HUGE TSUNAMI! EVACUATE!”

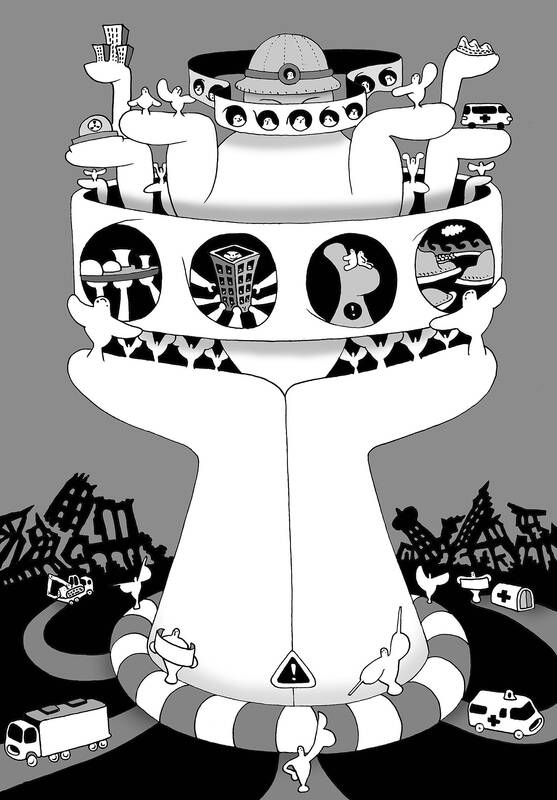

Illustration: Mountain People

The response was warranted: After 2011, authorities and TV networks were criticized for not being urgent enough, lulling some into a false sense of security, only to be swallowed by the ensuing tsunami. Doubtless, more deaths would be counted in Japan in the coming days; among them, the crew of the Japan Coast Guard aircraft involved in the collision at Tokyo’s Haneda airport, which struck a Japan Airlines flight carrying nearly 400. The smaller craft was preparing to ferry aid to the disaster zone.

Yet in many ways, the story of this disaster is one of what did not happen. Despite the record-level shaking, most buildings held up, with much of the damage so far coming in older dwellings, or those hit by fire or landslides. Nuclear plants close to the most severe shocks were unaffected. In perhaps the most telling example, not only were trains not derailed, but the Shinkansen bullet train that runs just 100km from the epicenter was back in full operation less than 24 hours after the event occurred.

Consider that the quake in Syria and Turkey almost one year ago, which had a similar magnitude of about 7.8, killed about 60,000 and caused tens of billions of dollars of damage. September’s temblor in Morocco killed nearly 3,000; another of just magnitude 5.9 in China’s Gansu Province had 150 fatalities.

There are types of disasters we are helpless against. We can do nothing about the pyroclastic flow of a volcano, nor the environmental effects as it shoots smoke and ash into the atmosphere. Hurricane forecasting has advanced hugely, but while we can evacuate in advance of a storm, our ability to prevent devastating economic damage remains limited, as seen with Hurricane Ian in 2022.

However, there is little excuse for developed nations to fail to erect now-proven systems and codes that can save lives. Earthquakes are a prime example. That so few deaths happened even in areas with the most severe shaking ever felt is not down to luck.

One widely circulated sight of the quake was that of a seven-story building that fell on its side in Wajima. That structure was built in 1972, a decade before an overhaul of Japan’s national building standards — one of many changes to the construction code that has been made since World War II, as the nation learned how to adapt to its frequent disasters. Those same standards are one reason I continue to be gung-ho on Japan’s unsentimental approach to razing old buildings and putting better ones in their place. Tsunami defenses also held up; critics love to blast Japan’s fondness for solving problems with concrete, but supposedly scenery-spoiling tetrapods and seawalls show their worth at times like this.

Nonetheless, the message here is not that the country is invulnerable. A magnitude 7.5 earthquake sounds (and is) big. However, the scale is logarithmic, meaning the magnitude 9 temblor that struck in 2011 released more than 125 times the energy as the New Year’s Day quake. It is not possible to build seawalls to prevent all the damage from such a tsunami; instead, we must learn from the past, and build away from these coasts over time.

That Japan was not hit harder on New Year’s Day is not serendipitous. Nevertheless, it is almost inevitable that it would suffer a more severe blow, and soon. A long-expected repeat of the 1923 quake that struck directly beneath Tokyo in 1923 could cause as many as 23,000 deaths from collapsed buildings and fires, according to government estimates. The country is racing to replace the stock of pre-1981 buildings, but even that would not eliminate the risk of fire.

The even greater specter is that of a quake hitting the Nankai Trough fault line, which runs along most of Japan’s Pacific coast. The government expects devastating tsunamis from such an event could kill as many as 320,000 people, more than an order of magnitude above the toll in 2011, and result in some ¥220 trillion (US$1.5 trillion) of damage.

However, as multiple regions have found in the past decade, from Tohoku, Kumamoto and now the Noto Peninsula, nowhere in the country is safe from risk. That holds true for other vulnerable areas, too, from California to China. The New Year’s Day quake is a warning: to shore up what we can and ready ourselves with emergency resources, evacuation plans and knowledge of what to do to minimize deaths for those calamities we cannot avoid.

Gearoid Reidy is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Japan and the Koreas. He previously led the breaking news team in North Asia, and was the Tokyo deputy bureau chief. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

US President Donald Trump is systematically dismantling the network of multilateral institutions, organizations and agreements that have helped prevent a third world war for more than 70 years. Yet many governments are twisting themselves into knots trying to downplay his actions, insisting that things are not as they seem and that even if they are, confronting the menace in the White House simply is not an option. Disagreement must be carefully disguised to avoid provoking his wrath. For the British political establishment, the convenient excuse is the need to preserve the UK’s “special relationship” with the US. Following their White House

Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention. If it makes headlines, it is because China wants to invade. Yet, those who find their way here by some twist of fate often fall in love. If you ask them why, some cite numbers showing it is one of the freest and safest countries in the world. Others talk about something harder to name: The quiet order of queues, the shared umbrellas for anyone caught in the rain, the way people stand so elderly riders can sit, the

After the coup in Burma in 2021, the country’s decades-long armed conflict escalated into a full-scale war. On one side was the Burmese army; large, well-equipped, and funded by China, supported with weapons, including airplanes and helicopters from China and Russia. On the other side were the pro-democracy forces, composed of countless small ethnic resistance armies. The military junta cut off electricity, phone and cell service, and the Internet in most of the country, leaving resistance forces isolated from the outside world and making it difficult for the various armies to coordinate with one another. Despite being severely outnumbered and

After the confrontation between US President Donald Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy on Friday last week, John Bolton, Trump’s former national security adviser, discussed this shocking event in an interview. Describing it as a disaster “not only for Ukraine, but also for the US,” Bolton added: “If I were in Taiwan, I would be very worried right now.” Indeed, Taiwanese have been observing — and discussing — this jarring clash as a foreboding signal. Pro-China commentators largely view it as further evidence that the US is an unreliable ally and that Taiwan would be better off integrating more deeply into