In the 1990s, as a 15-year-old high-school student in Uganda, I was a member of a “writers’ club” that would summarize for our fellow students key articles from the lone copy of the local newspaper our school received each day. One day, I was assigned a “news” article identifying the schools that were suspected of condoning or supporting homosexuality — and the students who were suspected of being gay. As I worked, my stomach ached for all the young people who would be shamed, ostracized and even beaten by their communities for their sexuality or gender identity. It ached for me, too, because I already knew — but had not said out loud — that I was queer.

Over time, that ache turned into anger, and that anger motivated me to fight back. So, when Uganda’s constitutional court begins hearings on the country’s Anti-Homosexuality Act — one of the world’s toughest anti-LGBTQ+ laws — I will be there, along with many other activists and allies, as a litigant. The hearings are the next battleground in the fight not only to protect the basic rights of queer Ugandans, but also to discredit non-Ugandan homophobes, such as Scott Lively and Sharon Slater, who have been pouring their resources into perpetuating bigotry around the world.

The Anti-Homosexuality Act, which Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni signed into law in May, is hardly Uganda’s first effort to criminalize same-sex relations. The country already has an anti-sodomy law in place — a legacy of British colonial rule.

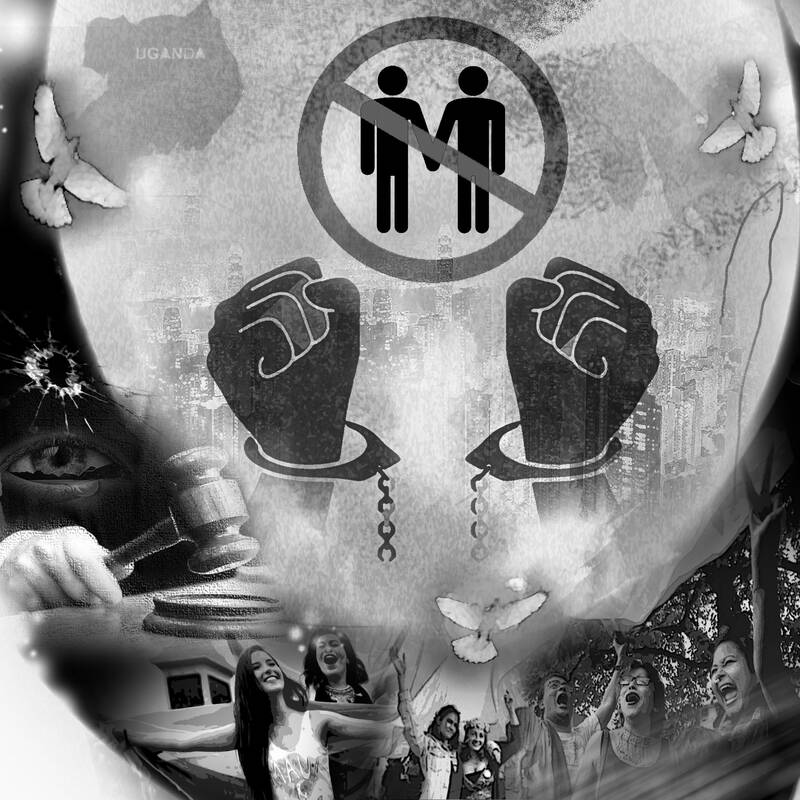

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

Moreover, in 2014, Uganda passed anti-homosexuality legislation that effectively laid the foundations for this year’s law.

The 2014 law was nullified by the courts on technical grounds. Yet the courts never ruled on the constitutionality of the rights at stake, so these issues are back before the court now. This is particularly important, because this year’s version takes an even harder line on consensual same-sex relations among adults, introducing both new crimes and harsher punishments.

For example, anyone who engages in the newly established crime of “aggravated homosexuality” — which includes consensual sex with a person with HIV — might face the death penalty. Among other consequences, this would impede the fight against HIV. After all, a vast body of evidence shows that such laws discourage people from revealing their status or even getting tested. At least two people in Uganda have already been charged with this new capital offense.

Another new crime is “promoting homosexuality” — that is, engaging in any advocacy for the rights of LGBTQ+ Ugandans — for which one could face up to 20 years in prison. Under this provision, even public health workers — Ugandan or otherwise — could face long prison sentences and hefty fines for implementing programs that bolster community health and well-being. As a queer activist, my personal and professional life make me a criminal in my country. Even before the latest law was passed, I was arrested many times for my activism or for just being myself.

Official punishments are only the beginning. A recent report by the Convening for Equality coalition, of which I am a leader, showed that the Anti-Homosexuality Law — and the hateful rhetoric surrounding it — has fueled a surge in human-rights violations against members of Uganda’s LGBTQ+ community, by both government employees and private citizens. In the first eight months of this year, we documented more than 300 such violations, including physical and online attacks, forced anal examinations ordered by police and healthcare discrimination.

I understand these assaults all too well. Like many other queer Ugandans, I have been shamed, ridiculed, bullied, beaten, robbed and even threatened with rape while in police custody. Once, I was beaten so badly that I lost my hearing and had to undergo surgery. In this latest wave of hysteria, I have faced death threats, cyberbullying, impersonation and blackmail.

Anti-gay sentiment in Uganda runs deep. Many Ugandans adhere to colonial religious values that have, over time, come to be regarded as “traditional” Ugandan values. As a result, homosexuality is spuriously presented as an assault on our country’s fundamental cultural and social norms. It does not help that conservative religious groups, particularly US-inspired Christian evangelicals and some Muslim leaders, also actively promote intolerance, discrimination and, at times, violence.

Yet, as the Anti-Homosexuality Act blatantly illustrates, Uganda’s government intends to lead the charge against homosexuality — an effort that threatens our very democracy. Laws that violate fundamental rights — to privacy, freedom of expression and non-discrimination — weaken the democratic order by defying the commitment to equality that underpins it. They also flout the timeless African concept of Ubuntu, or “humanity to others,” which is often understood to mean, “I am what I am because of who we all are.” African leaders who call for “African solutions to African problems” — a group that includes Museveni — should recognize what that truly means.

African leaders cannot claim to be devising “African solutions” to our challenges while excluding and attacking minority groups. They cannot purport to be advancing the cause of African self-determination while perpetuating colonial legacies of dehumanization and disregard for Africans’ needs and values. How could we possibly achieve true liberation when we criminalize and punish our citizens for being liberated in their own sexuality and identity?

This is not only an African issue. The liberation of Uganda’s LGBTQ+ people is inextricably tied to the liberation of all oppressed groups. That is why anyone who believes that all people are entitled to fundamental human rights should be watching closely as the upcoming constitutional court hearings unfold — and lending their voice to the cause.

I was three years old when I was orphaned; my father was murdered and his relatives cast my mother from our home. In one of the homes where I spent my formative years, I was lucky enough to find a safe space, where I could be myself. Most queer Ugandans are not so fortunate. If the Anti-Homosexuality Act is allowed to stand, there would be virtually no safe spaces left.

Pepe Julian Onziema, director of programs at Sexual Minorities Uganda, is a leader of the Convening for Equality’s Strategic Response Team. In 2014, he was named “Hero of the Year” by Stonewall, a UK-based charity.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Trying to force a partnership between Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) and Intel Corp would be a wildly complex ordeal. Already, the reported request from the Trump administration for TSMC to take a controlling stake in Intel’s US factories is facing valid questions about feasibility from all sides. Washington would likely not support a foreign company operating Intel’s domestic factories, Reuters reported — just look at how that is going over in the steel sector. Meanwhile, many in Taiwan are concerned about the company being forced to transfer its bleeding-edge tech capabilities and give up its strategic advantage. This is especially

US President Donald Trump’s second administration has gotten off to a fast start with a blizzard of initiatives focused on domestic commitments made during his campaign. His tariff-based approach to re-ordering global trade in a manner more favorable to the United States appears to be in its infancy, but the significant scale and scope are undeniable. That said, while China looms largest on the list of national security challenges, to date we have heard little from the administration, bar the 10 percent tariffs directed at China, on specific priorities vis-a-vis China. The Congressional hearings for President Trump’s cabinet have, so far,

The US Department of State has removed the phrase “we do not support Taiwan independence” in its updated Taiwan-US relations fact sheet, which instead iterates that “we expect cross-strait differences to be resolved by peaceful means, free from coercion, in a manner acceptable to the people on both sides of the Strait.” This shows a tougher stance rejecting China’s false claims of sovereignty over Taiwan. Since switching formal diplomatic recognition from the Republic of China to the People’s Republic of China in 1979, the US government has continually indicated that it “does not support Taiwan independence.” The phrase was removed in 2022

US President Donald Trump, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio and US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth have each given their thoughts on Russia’s war with Ukraine. There are a few proponents of US skepticism in Taiwan taking advantage of developments to write articles claiming that the US would arbitrarily abandon Ukraine. The reality is that when one understands Trump’s negotiating habits, one sees that he brings up all variables of a situation prior to discussion, using broad negotiations to take charge. As for his ultimate goals and the aces up his sleeve, he wants to keep things vague for