To the steady rat-tat-tat of machine guns and exploding bursts of smoke, amphibious tanks slice across a lake not far from the big green mountains that stand along the world’s most heavily armed border.

Dozens of South Korean and US combat engineers build a pontoon bridge to ferry tanks and armored vehicles across the water, all within easy range of North Korean artillery.

For seven decades, the allies have staged annual drills like this one to deter aggression from North Korea, whose 1950 surprise invasion of South Korea started a war that technically has yet to end.

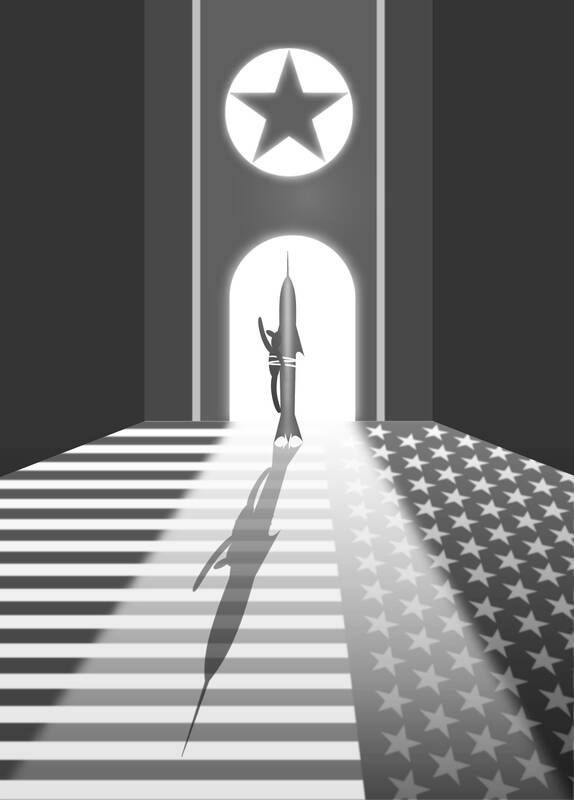

Illustration: Yusha

The alliance with the US has allowed South Korea to build a powerful democracy, its citizens confident that Washington would protect them if Pyongyang ever acted on its dream of unifying the Korean Peninsula under its own rule.

Until now.

With dozens of nukes in North Korea’s burgeoning arsenal, repeated threats to launch them at its enemies and a stream of tests of powerful missiles designed to pinpoint target a US city with a nuclear strike, a growing number of South Koreans are losing faith in the US’ vow to back its longtime ally.

The fear is that a US president would hesitate to use a nuclear weapon to defend the South from a North Korean attack, knowing that Pyongyang could kill millions of Americans with atomic retaliation.

Frequent polls show a strong majority of South Koreans — between 70 percent and 80 percent in some surveys — support their nation acquiring atomic weapons or urging Washington to bring back the tactical nuclear weapons it removed from South Korea in the early 1990s.

It reflects a surprising erosion of trust between nations that like to call their alliance an unshakable cornerstone of the US military presence in the region.

“I think one day they can abandon us and go their own way if that better serves their national interests,” Kim Bang-rak, a 76-year-old security guard in Seoul, said of the US. “If North Korea bombs us, we should bomb them equally in retaliation, so it would be better for us to have nukes.”

Underscoring those fears: Just hours before the US-South Korean tank drills began in Cheorwon, North Korean leader Kim Jong-un oversaw two ballistic missile test launches meant to simulate “scorched earth” nuclear strikes on South Korean command centers and airfields.

At the heart of South Korean unease is a broader debate over who gets to have nuclear weapons — a question that has anguished many nations since two US nuclear bombs flattened Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in 1945.

The sharp rise in support for South Korean nuclear weapons is not occurring in a vacuum. Nonproliferation experts say a vibrant global nuclear arms race shows little sign of slowing.

Nine countries — the US, Russia, the UK, France, China, India, Pakistan, North Korea and Israel — spent nearly US$83 billion last year on nuclear weapons, a recent report by the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons showed. That is an increase of US$2.5 billion from 2021, with the US alone spending US$43.7 billion.

How South Korea deals with the nuclear question could have major implications for Asia’s future, potentially jeopardizing the US-South Korean alliance and threatening a delicate nuclear balance that has so far kept an uneasy peace in a dangerous region.

“Ironclad.” That is how the US has long described its commitment to South Korea should a war begin. US officials are adamant that any attack on Seoul by North Korea’s 1.2 million-member military would be met with an overwhelming response.

The US, bound by treaty to defend Seoul and Tokyo, stations 28,500 troops in South Korea and another 56,000 in Japan. Tens of thousands of Americans live in greater Seoul, a sprawling area of 24 million people about an hour’s drive from the inter-Korean border.

“The ironclad commitment is not just words; it’s a reality. We’ve got thousands of troops right there,” then-chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley recently told reporters in Tokyo. An attack, the now-retired Milley said, “would spell the end of North Korea.”

Asked about the South Korean public’s support for creating its own nuclear force, Milley said, “The United States would prefer nonproliferation of nuclear weapons. We think they’re inherently dangerous, obviously. And we have extended our nuclear umbrella to both Japan and South Korea.”

South Korean Defense Minister Shin Won-sik said recently that he and his US counterpart signed a document in which Washington agreed to mobilize its full range of military capabilities, including nuclear capabilities, to defend the South from a North Korean nuclear attack.

Many in Seoul, however, would prefer nuclear weapons of their own.

North Korea’s only advantage over the South’s high-tech military is nuclear bombs, Kim Tae-il, a recent university graduate, said in an interview.

“So if South Korea gets nuclear weapons, we’ll secure an advantageous position where North Korea can’t rival us,” Kim said.

While the idea of South Korea pursuing nukes has been around for decades, it was rarely mentioned in public by senior government officials. That changed in January when conservative South Korean President Yoon Suk-Yeol said that his nation could “acquire our own nukes if the situation gets worse.”

“It would not take long,” he said, while also raising the possibility of requesting that the US reintroduce nuclear weapons into South Korea.

At an April summit in Washington, Yoon and US President Joe Biden took steps to address such South Korean worries. The result was the Washington Declaration, in which Seoul pledged to remain in the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty as a nonnuclear weapons state, and the US said it would strengthen consultations on nuclear planning with its ally. It also said it would send more nuclear assets to the Korean Peninsula as a show of force.

Not long after the meeting, the USS Kentucky became the first nuclear-armed US submarine to visit South Korea since the 1980s.

Opponents of South Korea obtaining nuclear weapons said they hope the declaration would reassure a nervous public.

“No one can tell 100 percent for sure” whether a US president would order nuclear strikes to defend Seoul if it meant the destruction of a US city, Wi Sung-lac, a former South Korean nuclear envoy, said in an interview at his Seoul office.

That is why the greater consultations called for between the allies in the Washington Declaration are needed to “manage the situation [so] we can tone down public anger and frustration,” he said.

Part of the worry in Seoul could be traced to the presidency of former US president Donald Trump — and to his possible re-election next year.

Trump, as president, repeatedly suggested that the alliance, far from “ironclad,” was transactional. Even as he sought closer ties with Kim Jong-un, Trump demanded South Korea pay billions of dollars more to keep US troops on its soil and questioned the need for US military exercises with South Korea, calling them “very provocative” and “tremendously expensive.”

“No matter how strong of a security commitment President Biden makes now, if someone who espouses isolationism and an America-first policy becomes the next US president, Biden’s current commitment can become a mere scrap of paper overnight,” Cheong Seong-chang, an analyst at the private Sejong Institute in South Korea, said in an interview.

South Korean support for nuclear weapons could also be linked to North Korea’s extraordinary weapons advancements and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

North Korea first tested an intercontinental ballistic missile capable of reaching the contiguous US in 2017. While the North is still working to overcome technological hurdles with its ICBMs, the weapons have fundamentally changed the region’s security calculus.

One of the poorest countries on Earth, North Korea might now have an arsenal of 60 nuclear weapons and has declared that it is deploying “tactical” missiles along the Korean border, implying its intent to arm them with lower-yield nuclear weapons.

While the two Koreas have avoided major conflict since the armistice halting the Korean War in 1953, deadly skirmishes and attacks in recent years have killed dozens.

If violence escalates, some observers believe that North Korea, outmatched by US and South Korean firepower and fearing for the safety of its leadership, could resort to using a tactical nuclear bomb.

“There is probably no conventional-only scenario in Korea anymore,” says Robert Kelly, a political science professor at Pusan National University in South Korea. “North Korea would rapidly lose a conventional conflict. Pyongyang ksnows this, dramatically raising the likelihood it will use nuclear weapons first, at least tactically.”

Russia’s war against Ukraine might also be showing South Koreans that even friendly nations may hesitate to fully help a country battling a nuclear-armed enemy. Kim Jong-un’s visit to Russia earlier this year, where he met Russian President Vladimir Putin and toured weapons facilities, has raised fears that North Korea could receive technology that would boost its nuclear program.

“We absolutely need nuclear weapons. Basically, peace can be maintained only when we have equal power to [our enemies],” said Kim Joung-hyun, a 46-year-old office worker in Seoul. “If you look at the Russia-Ukraine war, Ukraine can’t handle the Russian invasion on its own, other than begging for weapons from other countries.”

Opponents of a nuclear-armed South Korea say that strong public support for nukes likely does not calculate the high costs, nor the damage to ties with South Korea’s ally the US and to crucial trade with neighboring China. Seoul going nuclear could lead to sanctions targeting South Korea’s export-dependent economy. There is also concern it could encourage Tokyo to consider developing its own atomic weapons program.

Some are pushing for a less drastic solution to South Korea’s unique security worries.

“We don’t have other options except inviting American tactical nukes to the Korean Peninsula,” Cheon Seong-whun, a former presidential adviser to a past conservative government, said in an interview. This, he said, would allow South Korea to use those weapons if North Korea uses its tactical nukes, but would not harm its alliance with the US.

John Bolton, Trump’s national security adviser from 2018 to 2019, has written that redeploying US tactical nuclear weapons in South Korea would also “buy valuable time for Seoul and Washington to evaluate fully the implications of South Korea becoming a nuclear-weapons state.”

The Washington Declaration and high-level follow-up meetings between the allies have reassured many in Seoul, says Richard Lawless, a former senior US State Department and Central Intelligence Agency official dealing with nuclear proliferation in Asia.

“The [South Korean] nuclear option genie is not yet back in the bottle, but it is being successfully contained,” he told The Associated Press via e-mail.

Still, Lawless said, there remains “the deeply felt conviction among some senior politicians and among many in the populace” that the only real way to deter nuclear-armed North Korea is for South Korea to have its own nuclear weapons capability. “That concern is now mostly below the waves, but it remains and would be awakened with some passion.”

However the debate ends up, many in Seoul, on all sides of the issue, share another strong conviction. “There’s a 100 percent certainty that the North Korean threat will grow,” Cheon said. “North Korea will definitely not stay silent.”

Foster Klug is AP news director for the Koreas, Japan, Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific and has covered nuclear issues on the Korean Peninsula and in Asia since 2005.

The Associated Press receives support for nuclear security coverage from the Carnegie Corporation of New York and Outrider Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Trying to force a partnership between Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) and Intel Corp would be a wildly complex ordeal. Already, the reported request from the Trump administration for TSMC to take a controlling stake in Intel’s US factories is facing valid questions about feasibility from all sides. Washington would likely not support a foreign company operating Intel’s domestic factories, Reuters reported — just look at how that is going over in the steel sector. Meanwhile, many in Taiwan are concerned about the company being forced to transfer its bleeding-edge tech capabilities and give up its strategic advantage. This is especially

US President Donald Trump’s second administration has gotten off to a fast start with a blizzard of initiatives focused on domestic commitments made during his campaign. His tariff-based approach to re-ordering global trade in a manner more favorable to the United States appears to be in its infancy, but the significant scale and scope are undeniable. That said, while China looms largest on the list of national security challenges, to date we have heard little from the administration, bar the 10 percent tariffs directed at China, on specific priorities vis-a-vis China. The Congressional hearings for President Trump’s cabinet have, so far,

For years, the use of insecure smart home appliances and other Internet-connected devices has resulted in personal data leaks. Many smart devices require users’ location, contact details or access to cameras and microphones to set up, which expose people’s personal information, but are unnecessary to use the product. As a result, data breaches and security incidents continue to emerge worldwide through smartphone apps, smart speakers, TVs, air fryers and robot vacuums. Last week, another major data breach was added to the list: Mars Hydro, a Chinese company that makes Internet of Things (IoT) devices such as LED grow lights and the

The US Department of State has removed the phrase “we do not support Taiwan independence” in its updated Taiwan-US relations fact sheet, which instead iterates that “we expect cross-strait differences to be resolved by peaceful means, free from coercion, in a manner acceptable to the people on both sides of the Strait.” This shows a tougher stance rejecting China’s false claims of sovereignty over Taiwan. Since switching formal diplomatic recognition from the Republic of China to the People’s Republic of China in 1979, the US government has continually indicated that it “does not support Taiwan independence.” The phrase was removed in 2022