US President Joe Biden has adopted a two-pronged approach to constrain China’s high-tech progress, curbing Beijing’s access to leading-edge chips while bolstering semiconductor production in the US.

He is about to ratchet up the pressure further, shifting focus to an emerging arena of the contest for technological supremacy: the process of packaging semiconductors that is increasingly seen as a path to achieving higher performance.

Only the US is not alone is recognizing the potential of so-called advanced packaging: China, too, is capitalizing on an area that is not subject to sanctions, capturing global market share and achieving progress denied it in manufacturing high-end chips.

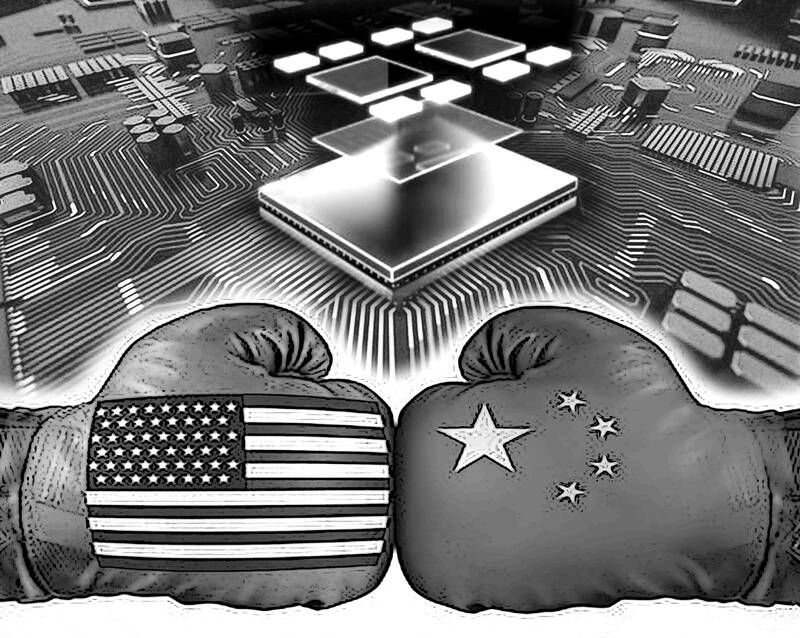

Illustration: Constance Chou

“Packaging is the new pillar of innovation in the semiconductor industry — it will change the industry drastically,” said Jim McGregor, founder of technology analysts Tirias Research.

For China, which does not have state-of-the-art capabilities, “it’s definitely easier for them to ramp up” here, since it is not restricted by the US government, he said. “Packaging could help them bridge the gap.”

Up until very recently, the business of packaging semiconductors — encasing chips in materials that both protect them and connect them to the electronic device they are part of — was, at best, an afterthought for the industry. So it was outsourced, mainly to Asia, with China a prime beneficiary: Today, the US accounts for just 3 percent of the global packaging capacity, according to Intel Corp.

Yet suddenly, advanced packaging is everywhere: Intel is banking on it as a core part of the US chip giant’s strategy to return to competitiveness; China sees it as a means of building out domestic semiconductor capacity; and now Washington is turning to it as part of its own plans for self-sufficiency.

More than a year after the US’ CHIPS and Science Act came into being, the Biden administration has outlined plans for a US$3 billion National Advanced Packaging Manufacturing Program, after recently tapping a director for the center. The goal is to create multiple high-volume packaging facilities by the end of the decade, said US Undersecretary of Commerce for Standards and Technology Laurie Locascio — and reduce reliance on Asian supply lines that pose a security risk the US “just can’t accept.”

Biden “has made it a priority to ensure America’s leadership in all elements of semiconductor manufacturing, of which advanced packaging is one of the most exciting and critical areas,” White House spokeswoman Robyn Patterson said.

With advanced packaging rapidly becoming a new front in the global conflict over chips, some argue it is long overdue.

The administration has until now focused on subsidies to bring back chip making to the US, but “we can’t ignore packaging because you can’t do one without the other,” said US Representative Jay Obernolte, who is one of two vice-chairs of the US Congressional Artificial Intelligence Caucus.

“It wouldn’t matter if we did 100 percent of our chip manufacturing onshore if the packaging is still offshore,” he added.

Assembly, testing and packaging — usually considered together as “back-end” manufacturing — was always the least glamorous end of the semiconductor industry, with less innovation and lower added value than the “front-end” business of making chips with features measured in the billionths of a meter. Yet the level of sophistication is rising fast as new technologies enable chips to be combined, stacked and their performance enhanced in what industry executives are calling an inflection point.

Advanced packaging cannot help China compete with leading-edge semiconductor developments from the US, but it allows Beijing to build faster, cheaper systems for computing by stitching different chips closely together. In that case China could save its latest chip technology, which is expensive and likely available in limited volume, for the most important part of the chip and use older, cheaper technologies to make chips that carry out other functions like battery management and sensor controls, combining the whole in a powerful package.

It is a “pivotal solution,” Bloomberg Intelligence technology analyst Charles Shum (沈明) said. “It doesn’t merely enhance chip-processing speed but crucially enables seamless integration of varied chip types.”

As a result, he said, it is “set to reshape the semiconductor-manufacturing landscape.”

Beijing has long made a strategic priority of semiconductor packaging technologies, including in Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) “Made in China” program announced in 2015. China has 38 percent of the world’s assembly, testing and packaging market, the most of any nation, the US-based Semiconductor Industry Association says.

While it lags behind Taiwan and the US in advanced technology, analysts agree that unlike in wafer processing, it is in a much better position to be able to catch up.

China already boasts the most back-end facilities by number, including the world’s third-largest assembly and testing company, Jiangsu Changjiang Electronics Technology Co (JCET), which trails only Taiwanese ASE Group and Amkor Technology of the US in revenue. What is more, Chinese companies are building market share, including through JCET’s acquisition of an advanced facility in Singapore and construction of an advanced packaging plant in its hometown of Jiangyin.

“For China, one way around technology transfer restrictions is advanced packaging, because so far it’s a safe space that everyone invests in,” said Mathieu Duchatel, a researcher at the Institut Montaigne think tank, a Taiwan-based China expert who studies the geopolitics of technology.

It is a realization now touching Washington as it seeks to deny Beijing access to the kind of advanced computing technologies that could be put to military use — with questionable success.

When Huawei Technologies Co quietly released its Mate 60 Pro smartphone in September, China hawks in Washington raised questions as to why US export controls had failed to prevent a development supposedly beyond Beijing’s capabilities.

In testimony to the US House Sept. 19, US Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo defended the Biden administration’s focus on denying China access to leading-edge chips and the equipment to make them.

However, she was primed on advanced packaging. The US needs to ramp up its own advanced packaging capacities, she said, since “chips can only get so small, which means all the special sauce is in the packaging.”

One reason for the sudden focus on that special sauce is its necessity to the kind of high-power semiconductors needed for artificial intelligence (AI) applications. Indeed, a shortage of a particular type of packaging known as chip-on-wafer-on-substrate (CoWoS) is a key bottleneck in the production of Nvidia Corp’s AI chips.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), the main chip maker for Nvidia, this summer committed US$3 billion to a packaging plant to help alleviate the blockage. TSMC CEO C.C. Wei (魏哲家) told investors on the company’s third-quarter earnings call that the company planned to double CoWoS capacity by the end of next year.

While TSMC has been working on the technology for 12 years, it was a niche application that only took off this year, the company’s vice president of advanced packaging technology Jun He told a conference in Taipei last month.

“We’re building capacity like crazy,” Jun He said, adding that “everybody, probably even in Starbucks,” is talking about CoWoS.

It is not just TSMC. Micron Technology Inc is setting up a US$2.75 billion back-end facility in India, while Intel agreed to build a US$4.6 billion assembly and test plant in Poland and is putting about US$7 billion into advanced packaging in Malaysia. South Korean SK Hynix Inc said last year that it plans to invest US$15 billion in a packaging facility in the US.

Intel has “some very unique technology now in the packaging area,” the company’s CEO Pat Gelsinger said in an interview. “Everybody who’s doing AI chip work today is looking to say, wow, this is the way that I can advance my AI chip capabilities.”

That has some analysts predicting a bonanza for companies in the sphere. According to McKinsey & Co, high-performance chips for data centers, AI accelerators, and consumer electronics would create the greatest demand for advanced packaging technologies.

The number of chips shipped that use advanced packaging is forecast to increase tenfold in the next 18 months — but that could soar to 100 times if it becomes standard in smartphones, Jeffries analysts Mark Lipacis and Vedvati Shrotre wrote in a Sept. 14 report that classed the technology as part of a “tectonic shift” in the industry.

The reason, alluded to by Raimondo, is that chip making is running up against the limits of physics.

Chips have been getting better in the past fifty years in large part through advances in production technology. The components now contain up to tens of billions of the tiny transistors that give them the ability to store or process information.

However, now that path of advancement, called Moore’s law after Intel’s founder, is coming up against fundamental barriers that are making improvements more difficult and vastly expensive to achieve.

Moore’s law — more of an observation — states that the number of transistors on a chip doubles about every two years.

As that pace of progress slows, and companies “are not able to deliver twice the transistors, at half the cost, at twice the clock speed, and at lower power levels every two years, the industry has begun to rely more on advanced packaging techniques to pick up the slack,” Lipacis and Shrotre wrote.

Instead of cramming ever more tiny components on to one piece of silicon, many designers and companies are touting the benefits of a modular approach, of building products out of several “chiplets” tightly packed together in the same package.

That explains why Dutch specialist BE Semiconductor Industries NV, which makes the tools used for chip packages, has doubled its value to about US$9.8 billion in the past 12 months, outpacing the Philadelphia Semiconductor Index two-fold despite a slump in the chip industry in the second half of this year. That is still dwarfed by the kind of sums involved in front-end manufacturing — fellow Dutch firm ASML NV, which has a near monopoly on the machines needed to produce leading-edge semiconductors, has a market cap approaching US$250 billion. Intel’s cutting-edge chip fabrication plant in the eastern German city of Magdeburg has a price tag of US$30 billion, or more than four times its Malaysia commitment.

Yet between Magdeburg, a new site in Ireland and its Polish plant with capacity for advanced packaging, “Poland could actually be the most important,” Gelsinger said.

Chinese companies are piling into the space, too. They include Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp — China’s largest chipmaker, which made the 7-nanometer chip powering the Mate 60 Pro — along with IP leader VeriSilicon Co and Huawei, Berlin-based researchers Jan-Peter Kleinhans and John Lee said.

These companies “see potential in utilizing advanced packaging processes to achieve performance gains without relying on foreign cutting-edge front-end processes,” Kleinhans and Lee, of the Stiftung Neue Verantwortung think tank and East West Futures consultancy respectively, wrote in a report.

The US Department of Commerce justifies its decision to focus on front-end manufacturing on the grounds that sanctioning assembly, test and packaging (APT) services would disrupt supply chains without reducing national security risks. China’s APT services “now play a critical and indispensable role in the global supply chain,” and “cannot easily be substituted,” the US National Institute of Standards and Technology said.

The Biden administration has “taken necessary actions to prevent advanced US technologies related to semiconductors from being used in ways that undermine our national security, and we are continuously evaluating whether additional actions are warranted to keep pace with technological developments,” Patterson said.

The irony is that attracting the likes of TSMC and Samsung Electronics Co to construct cutting-edge chip plants in Arizona and Texas does not ensure self-reliance, since the current lack of capacity means the advanced wafers those plants produce would need to be shipped to Asia to be packaged — most likely in Taiwan.

For IBM Global Enterprise Systems Development vice president Jack Hergenrother, advanced packaging is relatively “overlooked” in funding terms. He wants double the allocation to help spur a rise in US packaging capacity to 10 to 15 percent of the global total, and ideally to take 25 percent in a decade, to ensure a secure supply chain.

“Having a hub in North America for advanced packaging is super important,” he said.

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) caucus whip Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) has caused havoc with his attempts to overturn the democratic and constitutional order in the legislature. If we look at this devolution from the context of a transition to democracy from authoritarianism in a culturally Chinese sense — that of zhonghua (中華) — then we are playing witness to a servile spirit from a millennia-old form of totalitarianism that is intent on damaging the nation’s hard-won democracy. This servile spirit is ingrained in Chinese culture. About a century ago, Chinese satirist and author Lu Xun (魯迅) saw through the servile nature of

In their New York Times bestseller How Democracies Die, Harvard political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt said that democracies today “may die at the hands not of generals but of elected leaders. Many government efforts to subvert democracy are ‘legal,’ in the sense that they are approved by the legislature or accepted by the courts. They may even be portrayed as efforts to improve democracy — making the judiciary more efficient, combating corruption, or cleaning up the electoral process.” Moreover, the two authors observe that those who denounce such legal threats to democracy are often “dismissed as exaggerating or

Monday was the 37th anniversary of former president Chiang Ching-kuo’s (蔣經國) death. Chiang — a son of former president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), who had implemented party-state rule and martial law in Taiwan — has a complicated legacy. Whether one looks at his time in power in a positive or negative light depends very much on who they are, and what their relationship with the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is. Although toward the end of his life Chiang Ching-kuo lifted martial law and steered Taiwan onto the path of democratization, these changes were forced upon him by internal and external pressures,

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) caucus in the Legislative Yuan has made an internal decision to freeze NT$1.8 billion (US$54.7 million) of the indigenous submarine project’s NT$2 billion budget. This means that up to 90 percent of the budget cannot be utilized. It would only be accessible if the legislature agrees to lift the freeze sometime in the future. However, for Taiwan to construct its own submarines, it must rely on foreign support for several key pieces of equipment and technology. These foreign supporters would also be forced to endure significant pressure, infiltration and influence from Beijing. In other words,