A wave of evictions recently hit Dakar’s bustling Liberte 6 market, a roughly mile-long commercial hub that has served its community for more than 20 years. Hundreds of street vendors’ stalls were bulldozed to make way for a new bus system. Authorities gave prior notice and an indemnity to help with the loss of business, but did not address the real problem: the lack of spaces for trading.

Street vending is a legitimate economic activity that provides livelihoods for millions and accounts for a large share of urban employment in many cities across the Global South. Nearly 59,000 street vendors work in Dakar, accounting for 13.8 percent of total employment, while metropolitan Lima has roughly 450,000, comprising 8.8 percent of total employment. These numbers are also likely growing as the informal economy absorbs many of those left unemployed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is a livelihood that requires one resource above all: access to busy, pedestrian-friendly, well-connected and affordable public spaces. Yet government authorities focus instead on “cleaning up” cities, which means clearing the streets of vendors. In their view, informal traders are a nuisance: They litter and clutter streets, obstruct urban mobility and occupy precious space that could be used for modernization or beautification projects, or sold to deep-pocketed developers and transformed into oases of leisure for urban elites.

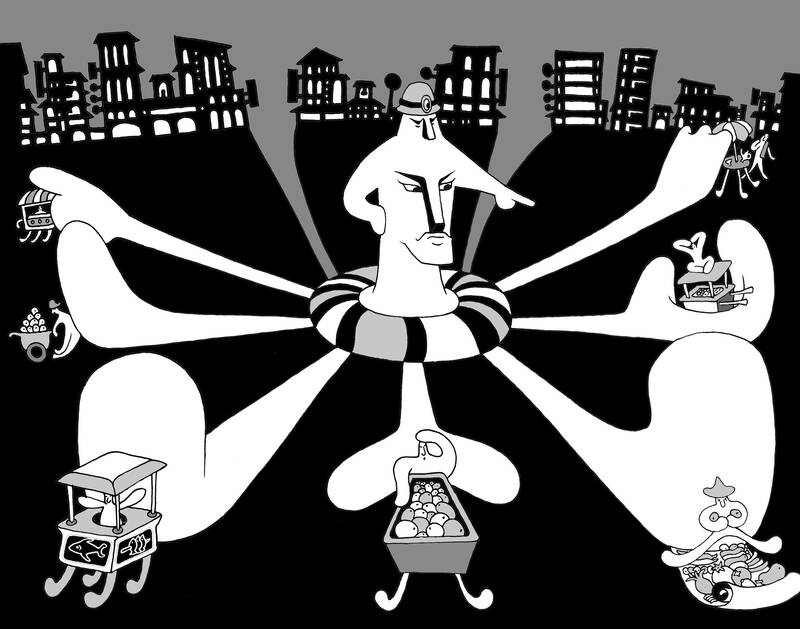

Illustration: Mountain People

The failure to provide street vendors with the space they need is short-sighted at best (eviction campaigns never solve the problem — workers often have no choice but to set up shop again). In 2015, the International Labor Organization recommended that subsistence workers be permitted to use public space as member states transition from informal to formal economies. Yet time and again, governments have implemented narrow policies and legal frameworks that curtail access.

This pattern has become embedded in policymakers’ strategies to formalize the informal economy. These strategies, focused mainly on getting informal workers to register and pay taxes, could provide important opportunities, including access to social protection, financing and professional training. However, they almost never recognize public spaces as a workplace, perpetuating the status quo. Instead, they build complex structures on shaky foundations — namely, punitive legal and policy frameworks that criminalize informal trading and deny access to economic activities to the most vulnerable people.

Proposals to relocate street vendors to enclosed markets are often empty promises — or implemented with little or no consultation with the affected individuals, resulting in poorly planned, difficult-to-reach markets, far from the city’s commercial hubs. Vendors either shun or quickly abandon them, returning instead to the streets from which they were removed.

Acutely aware of their precarity, street vendors usually have one goal: to trade without fear of harassment or eviction.

“I know we are not allowed to work here, but I have a family to feed,” said an informal worker selling mobile phones from a small kiosk in Guediawaye, a municipality on the outskirts of Dakar, said in an interview last year conducted by my organization, Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO).

“All I want is to be able to work and make a living,” added the man, who asked not to be named.

Pointing to an empty patch of land across the street, he said: “With other vendors, we asked the municipality to authorize us to sell there, but we got no response.”

The UN’s New Urban Agenda, adopted in 2016, recognizes that public space could function as a workplace reality and supports measures that allow for the “best possible commercial use of street-level floors, fostering both formal and informal local markets and commerce.” A legal framework that guarantees informal vendors access to this space must underpin any formalization strategy. It is a logical prerequisite for all other aspects of formalization, such as registration and taxation.

Of course, as a scarce resource, urban public space is highly sought after and there are many competing interests. Yet its effective management requires input from workers in informal employment, as various initiatives have demonstrated. In India, for example, the 2014 Street Vendors Act established “town vending committees,” consisting of government officials, sellers and others, to make decisions about trading locations and monitor evictions and relocations. In the 1990s, the Lima municipality involved street vendors from the outset in its relocation planning process to ensure that they had proper access to infrastructure and customers. From 2009 to 2011, the Dakar municipality started an effective dialogue with informal traders about relocation.

These examples are far from perfect. The inclusive planning process was discontinued in Lima (although it did result in successful relocations), as were the dialogues in Dakar, while India’s Street Vendors Act has only been partially implemented. However, they all show that the inclusive management of public space is possible.

Fair distribution of public space is crucial to recognizing street vendors, legalizing their access to a workplace and protecting their livelihoods. That cannot happen unless informal traders participate in — and meaningfully influence — the policies and regulations that affect them.

Teresa Marchiori, an adjunct professor at American University, is an access to justice lawyer at WIEGO.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Why is Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) not a “happy camper” these days regarding Taiwan? Taiwanese have not become more “CCP friendly” in response to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) use of spies and graft by the United Front Work Department, intimidation conducted by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the Armed Police/Coast Guard, and endless subversive political warfare measures, including cyber-attacks, economic coercion, and diplomatic isolation. The percentage of Taiwanese that prefer the status quo or prefer moving towards independence continues to rise — 76 percent as of December last year. According to National Chengchi University (NCCU) polling, the Taiwanese

US President Donald Trump is systematically dismantling the network of multilateral institutions, organizations and agreements that have helped prevent a third world war for more than 70 years. Yet many governments are twisting themselves into knots trying to downplay his actions, insisting that things are not as they seem and that even if they are, confronting the menace in the White House simply is not an option. Disagreement must be carefully disguised to avoid provoking his wrath. For the British political establishment, the convenient excuse is the need to preserve the UK’s “special relationship” with the US. Following their White House

It would be absurd to claim to see a silver lining behind every US President Donald Trump cloud. Those clouds are too many, too dark and too dangerous. All the same, viewed from a domestic political perspective, there is a clear emerging UK upside to Trump’s efforts at crashing the post-Cold War order. It might even get a boost from Thursday’s Washington visit by British Prime Minister Keir Starmer. In July last year, when Starmer became prime minister, the Labour Party was rigidly on the defensive about Europe. Brexit was seen as an electorally unstable issue for a party whose priority

After the coup in Burma in 2021, the country’s decades-long armed conflict escalated into a full-scale war. On one side was the Burmese army; large, well-equipped, and funded by China, supported with weapons, including airplanes and helicopters from China and Russia. On the other side were the pro-democracy forces, composed of countless small ethnic resistance armies. The military junta cut off electricity, phone and cell service, and the Internet in most of the country, leaving resistance forces isolated from the outside world and making it difficult for the various armies to coordinate with one another. Despite being severely outnumbered and