The overuse of antibiotics is widely recognized as one of the main factors contributing to antimicrobial resistance (AMR), often called the “silent pandemic,” but what is less well-known is that shortages of antibiotics also play a role in fueling it.

Scarce supplies of pediatric amoxicillin, used to treat Strep A, made headlines in the UK late last year, as a surge of infections left at least 19 children dead. From being an outlier, such shortfalls are common and pervasive, affecting countries across the world, and their consequences for individuals’ health and AMR’s spread can be dire.

That is because shortages of first-line antibiotics often lead to overuse of those that are specialized or kept in reserve for emergencies. Not only can these substitutes be less effective, but reliance on them increases the risk of drug resistance developing and infections becoming more difficult to treat in the long-run.

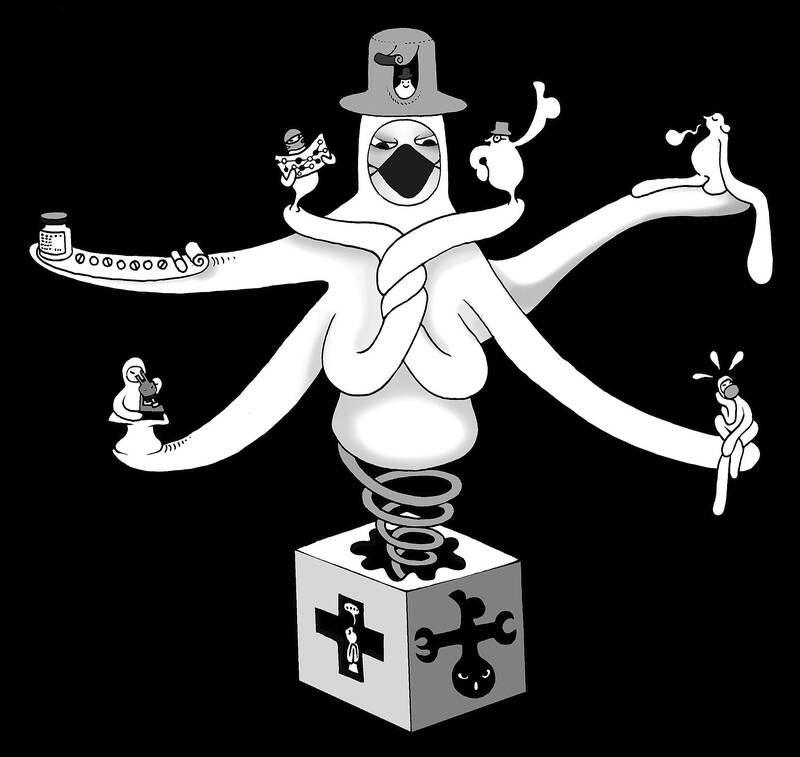

Illustration: Mountain People

Already one of the world’s biggest killers, AMR is on the rise. In 2019, it was directly responsible for an estimated 1.27 million deaths — more than HIV/AIDS and malaria combined — and associated with 4.95 million more.

So far, the global response to this growing crisis has focused mainly on trying to outpace drug-resistant bacteria through the development of new antibiotics.

Yet in the short term, there is ample room to reduce the number of AMR deaths, as well as AMR’s impact on health more broadly, by addressing some of the causes of shortages and improving access to appropriate treatments.

The same market failures that triggered the global AMR crisis are also largely responsible for antibiotic shortages. Compared with other drugs, antibiotics are often more complex and more costly to manufacture, have stricter regulatory requirements and are less profitable. As a result, many pharmaceutical companies have significantly reduced or stopped antibiotic research and development over the past few decades.

Not only are very few new antibiotics being developed, but it has also become less attractive to produce those already on the market, partly due to supply chain bottlenecks and volatility. All it takes is a disruption in the supply of an ingredient or a quality-control problem, or a supplier increasing prices or halting production entirely, to bring the global supply chain of these medicines to a standstill.

Just as important has been the equally volatile demand for antibiotics caused by sudden outbreaks of bacterial infections and poor management of national supplies, which contributes to stockouts. While shortages are not uncommon in the pharmaceutical industry, they are 42 percent more likely for antibiotics than they are for other drugs.

Although precise numbers that would reveal the scale of the problem are difficult to obtain, much of this uncertainty could be avoided with better market intelligence. Even though antibiotics are less lucrative than other drugs, pharmaceutical companies can still turn a profit — if they have accurate data. Improved forecasting can thus reduce risks for manufacturers and provide them with an incentive to scale up production and expand their markets.

There is also plenty of room for improvement in the way that countries — particularly lower-income nations — procure, register and manage these vital drugs.

For example, by expanding the capacity of national regulatory authorities, it would be easier to track and coordinate supplies and create stockpiles to build greater resilience. All of this would also help provide more certainty for drugmakers.

SECURE, an initiative led by the WHO and the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (of which I am executive director), aims to work with countries to improve access to essential antibiotics. That involves exploring how national regulatory authorities could serve as centralized hubs to help monitor, prevent and respond to shortages.

Eventually, SECURE intends to create more buoyant and competitive markets by encouraging countries to pool procurement, ensuring a more reliable supply.

Shortages of antibiotics are a serious problem for all countries, but there is plenty that can — and should — be done to prevent them. Given the accelerating spread of AMR and the long lead-in time to develop antibiotics, the problem can no longer be overlooked.

Equally important, efforts to address scarce supplies could help ensure that, when new drugs become available, they reach the people who need them.

Manica Balasegaram is executive director of the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its