Poland — whose eight years of euroskeptic, conservative rule under the Law and Justice (PiS) party put it in the same illiberal camp as Viktor Orban’s Hungary — now looks headed for closer ties with the EU. Sunday’s early parliamentary election arithmetic suggests Donald Tusk is set to return as prime minister, aiming to restore the rule of law and align Poland’s foreign policy along a more pro-Ukraine line. The optimism among financial markets and Western corridors of power is warranted — but so is caution over the uphill climb ahead.

The election was PiS’ to lose, and lose it effectively did, despite technically coming in first among the parties with a 35.4 percent share of the vote. Record turnout and frustration with the country’s illiberal turn and stalling economic growth gave a boost to anti-PiS forces led by Tusk’s Civic Platform party; joining forces with Third Way and the Left would give the group an estimated 248 seats in the 460-strong lower house of parliament.

“The pendulum has swung back,” Lukas Macek of the Jacques Delors Institute think tank said, adding that voters appear to have rejected PiS’ polarized culture-war narrative.

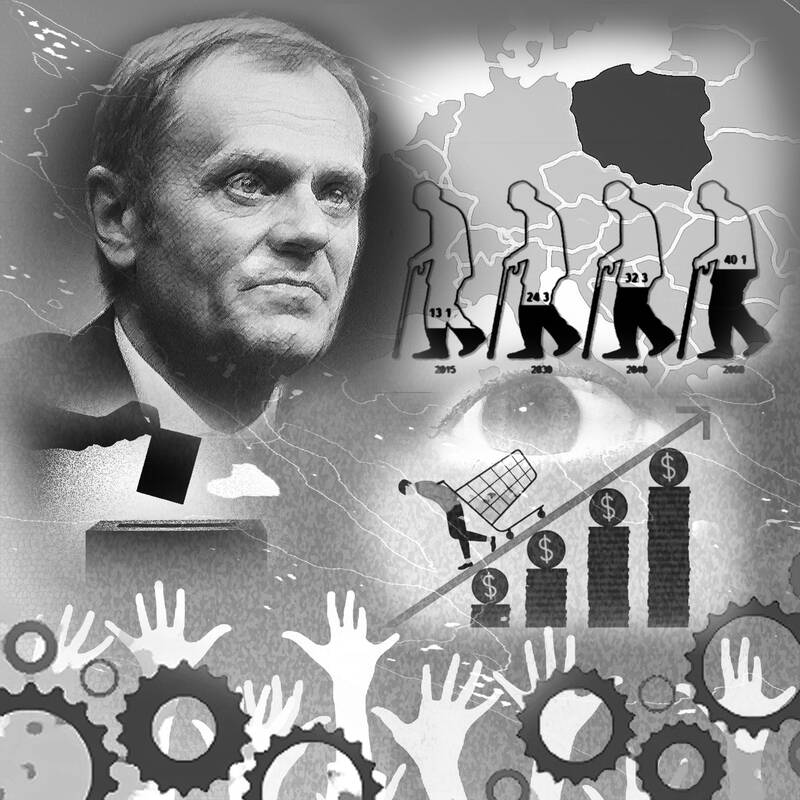

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

This is a big deal, politically and economically, as the bounce in investor optimism suggests. The chance to repair ties with the EU after years of bust-ups means a potential re-anchoring of a major economy in a central region once described by writer Milan Kundera as belonging culturally to the West and politically to the East. At stake is the release of more than 35 billion euros (US$37 billion) of EU funds earmarked for Poland, but trapped in a fight over judicial independence; better relations with Berlin and Paris; increased support for Ukraine after a grain dispute; and liberalization of abortion laws. Poland’s economy has been a success in recent decades, but its more nationalist-statist turn under PiS has worried some foreign investors.

After what felt like a clean sweep of victories for authoritarian leaders in Hungary, Turkey and most recently Slovakia, Poland is a warning to politicians who expect the recipe of polarization, scapegoating and budget giveaways to work every time.

Tusk might be a divisive figure, seen by some as too socially left and too economically right, but bashing him as a covert agent of Germany or Russia seems to have had the opposite effect than intended by turning voters off to an all-or-nothing clash of ideologies. Rising support for centrists also suggests that the PiS tactic of spending cash “like a firehose,” on everything from expanded child benefits to the elderly, can also backfire. Its high-welfare, high-conservatism vision has failed to rally Poles this time.

With the optimism, however, comes caution. The challenge facing Poland is big — nothing less than a “new chapter in the history of European democracy,” said Piotr Buras, head of the European Council on Foreign Relations’ Warsaw office.

As the ugliness of the campaign rhetoric suggests, the months ahead will be rough: PiS-backed Polish President Andrzej Duda is still in power until 2025 and will likely make life difficult for Tusk and his would-be coalition partners, both in forming a government and adopting reforms necessary to shift the still-divided country in a new direction.

Poland is a young country in its current form: It entered the post-Soviet era in 1989, joined NATO in 1999, joined the EU in 2004, and has been successful in catching up economically to the West and in carving out its own foreign-policy path. This is now another slice of uncharted territory for a country facing challenges common to many of its neighbors — an aging population, higher inflation and the pressure of decarbonization in a carbon-intensive economy. A change in parliament is only the first step.

“This is the end of the bad time,” Tusk said.

Let us hope he is right.

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist writing about the future of money and the future of Europe. Previously, he was a reporter for Reuters and Forbes. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its