The world’s massive human population is leveling off. Most projections show we would hit peak humanity in this century, as people choose to have smaller families and women gain power over their own reproduction. This is great news for the future of our species.

And yet alarms are sounding. While environmentalists have long warned of a planet with too many people, now some economists are warning of a future with too few. For example, economist Dean Spears from the University of Texas has written that an “unprecedented decline” in population would lead to a bleak future of slower economic growth and less innovation.

However, demographers I spoke with say this concern is based more on speculation than science. A dramatic collapse in population is unlikely to happen within the next 100 years barring some new plague or nuclear war or other apocalypse. If we need more creative minds in the world, we could stop doing such a terrible job of nourishing and educating the people we are already producing.

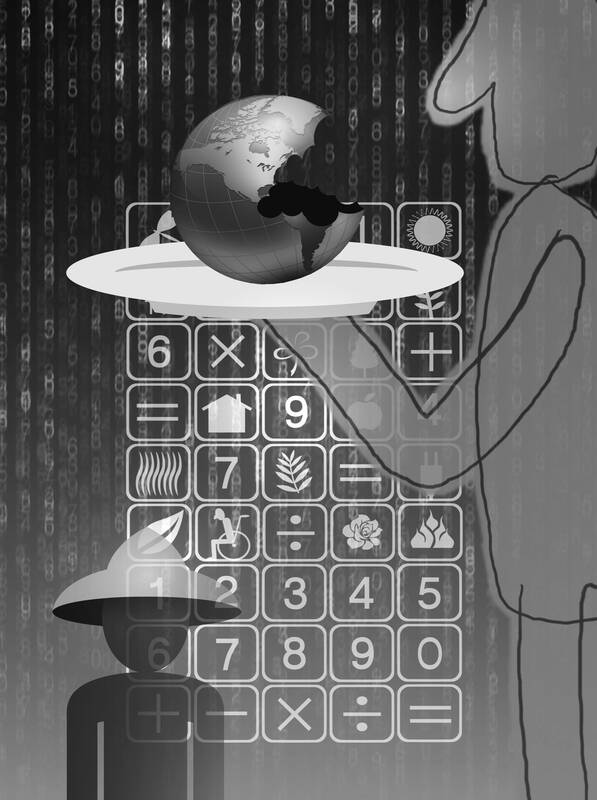

Illustration: Yusha

Predictions about future population levels that do not come with wide margins of error should always be taken with a grain of salt. Joel Cohen, a mathematician, biologist and demographer at Rockefeller University, wants to see population projections treated like a real science with a proper accounting for uncertainty. We do not even know the exact number of people alive now, he points out. When the UN declared we would surpassed 8 billion on Nov. 15 last year, it was a “publicity stunt,” he says.

The uncertainty in counting world populations is at least 2 percent — which adds up to about 160 million people or more. Since the world population grows at most by 80 million a year, we could have hit 8 billion two years earlier, or it might not happen until next year.

Benjamin Franklin first recognized populations can grow exponentially and forecast that the US colonies would double every 25 years. In 1798, English economist Thomas Malthus applied this principle globally and wrongly predicted this growth rate would continue until we ran out of food and civilization collapsed.

This line of pessimistic thinking might sound familiar to those who remember the 1968 book by Stanford University scientists Paul and Anne Ehrlich, The Population Bomb. The Ehrlichs famously — and incorrectly — envisioned a 20th-century starvation catastrophe. They failed to recognize that technological advances might meet increased need, and that women worldwide would change from having six to slightly under two children each, on average, in the next 50 years.

Today’s forecasts account for multiple variables and recognize that population increases are leveling off, not spiking and then plummeting. Some of the most reliable projections, Cohen said, come from demographers with the UN. Their latest estimate shows the global population would plateau at about 11 billion people by 2100.

A different model, created by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation and published in The Lancet in 2020, showed an earlier, lower peak about 2064 at 9.7 billion, followed by a steady decline, bringing us down to around 6 billion by 2100. Cohen does not find that alarming — that is about the number of people alive in 2000.

That inevitable rise in the near term worries Daniel Blumstein, an ecologist at UCLA who is coauthor of a 2021 paper on avoiding a “ghastly future” (co-authored with, among other researchers, the Ehrlichs). Population and consumption patterns are intertwined, he said, and together are causing multiple environmental problems, some of them irreversible.

Blumstein said that the innovations in agriculture that Malthus and the Ehrlichs failed to account for have allowed our population to swell far beyond our ecological niche — with unintended consequences.

Pesticides, for example, are killing the bees necessary for pollinating crops. The big picture: Buildup of waste, especially carbon dioxide, along with the destruction of habitat for wild plants and animals, are now threatening humans more than a shortfall in the global supply of food. These changes are contributing to valid concerns about the creation of climate refugees.

There are also real reasons to be concerned about how society would adapt to an aging population. In many countries, the elderly make up a large and growing share of people. Nicholas Eberstadt, a demographer and economist from the American Enterprise Institute, said most countries are already reproducing below replacement level, except for the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa. Even China’s massive population has begun to shrink, and India’s fertility has fallen below replacement level.

People are not selfish for choosing smaller families. We are powerfully programmed by Darwinian evolution to want to have offspring, or at least to have sex, but women are also endowed with the instinct to limit reproduction to the number who can be raised with a high probability of success in life. When women have large numbers of children, it is often a result of high child mortality or lack of power over their own lives.

Those warning that a population drop could decrease collective brain power and hurt the economy overlook a better solution than producing more babies: Taking better care of the ones we have.

About 22 percent of children under five today are too short for their age because they do not get enough of the right kinds of nutrients to grow, and because worms and infections compete for the inadequate food they do get, Cohen said.

That can affect not only the body, but the brain. Eberstadt worries about future mismatches between skilled jobs and an undereducated population.

Taking good care of the next generation is the logic parents around the world apply to their own families — and while it would not solve all our environmental and economic problems, it is a start.

F.D. Flam is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering science. She is host of the Follow the Science podcast. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Why is Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) not a “happy camper” these days regarding Taiwan? Taiwanese have not become more “CCP friendly” in response to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) use of spies and graft by the United Front Work Department, intimidation conducted by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the Armed Police/Coast Guard, and endless subversive political warfare measures, including cyber-attacks, economic coercion, and diplomatic isolation. The percentage of Taiwanese that prefer the status quo or prefer moving towards independence continues to rise — 76 percent as of December last year. According to National Chengchi University (NCCU) polling, the Taiwanese

It would be absurd to claim to see a silver lining behind every US President Donald Trump cloud. Those clouds are too many, too dark and too dangerous. All the same, viewed from a domestic political perspective, there is a clear emerging UK upside to Trump’s efforts at crashing the post-Cold War order. It might even get a boost from Thursday’s Washington visit by British Prime Minister Keir Starmer. In July last year, when Starmer became prime minister, the Labour Party was rigidly on the defensive about Europe. Brexit was seen as an electorally unstable issue for a party whose priority

US President Donald Trump’s return to the White House has brought renewed scrutiny to the Taiwan-US semiconductor relationship with his claim that Taiwan “stole” the US chip business and threats of 100 percent tariffs on foreign-made processors. For Taiwanese and industry leaders, understanding those developments in their full context is crucial while maintaining a clear vision of Taiwan’s role in the global technology ecosystem. The assertion that Taiwan “stole” the US’ semiconductor industry fundamentally misunderstands the evolution of global technology manufacturing. Over the past four decades, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, led by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), has grown through legitimate means

Today is Feb. 28, a day that Taiwan associates with two tragic historical memories. The 228 Incident, which started on Feb. 28, 1947, began from protests sparked by a cigarette seizure that took place the day before in front of the Tianma Tea House in Taipei’s Datong District (大同). It turned into a mass movement that spread across Taiwan. Local gentry asked then-governor general Chen Yi (陳儀) to intervene, but he received contradictory orders. In early March, after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) dispatched troops to Keelung, a nationwide massacre took place and lasted until May 16, during which many important intellectuals