Everyone needs a foil, and for many who are focused on climate and sustainability, economic growth — capitalism — is a convenient target. This is understandable. Economic expansion is the quintessential capitalist imperative, but infinite material growth on a finite planet is physically impossible. Hence the rise of “degrowth,” “agrowth,” “post-growth” and other concepts that have emerged to underpin seemingly sophisticated criticisms of the “standard” economic model.

Look beneath the surface and you will find that this clash of worldviews is more about rhetoric than actual policy. It is also a distraction.

The focus instead must be on cutting carbon and other forms of pollution. While high-carbon, low-efficiency economic activities — and some entire sectors — must shrink, low-carbon, high-efficiency activities and sectors must grow. Harnessing this natural process of “creative destruction” does not mean embracing laissez-faire, with policymakers sitting on the sidelines watching passively.

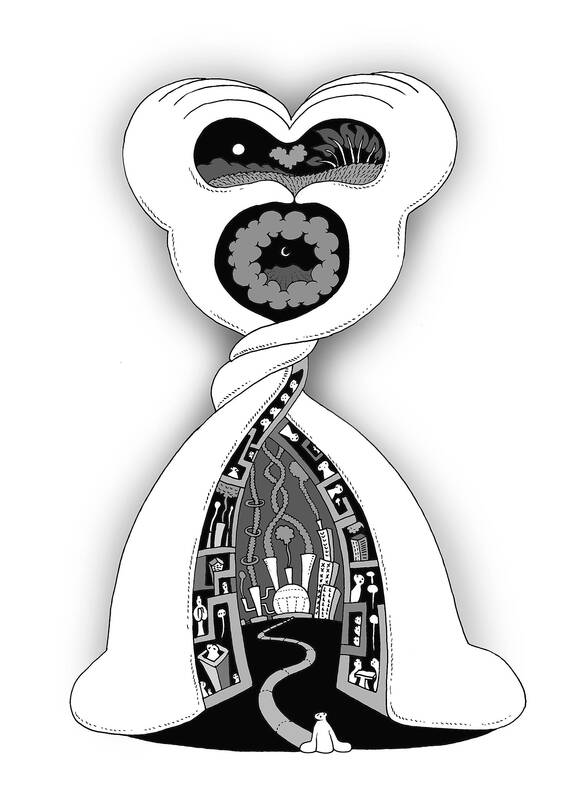

Illustration: Mountain People

Consider the massive negative societal costs associated with burning oil, coal and gas. According to the best estimates we have, the social cost of carbon in the US has nearly quadrupled in the past decade, from about US$45 per tonne of emitted carbon dioxide to almost US$180 — and even that is only a partial estimate of the true costs.

All told, each barrel of oil and each tonne of coal burned cause more in external damage than they add to GDP — and we have not even yet accounted for other important environmental factors such as land use and biodiversity. Given these high and mounting costs, the policy prescription has long been clear: put a price on carbon. Or better yet, price any and all negative externalities, and subsidize the positive ones.

Last year’s US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) nods in both of these directions, but while it includes a little-known direct price for methane emissions from oil and gas operations, its main focus is on subsidies and tax credits. By harnessing the potential of markets and incentivizing economic growth in specific areas, it represents “green industrial policy” in action.

Such active government involvement in the economy raises a host of questions. What is not in doubt is that hundreds of billions of US dollars of government subsidies would drive the deployment of renewable energy, battery storage, clean transportation and other important technologies in underdeveloped sectors. Moreover, all that development would generate economic growth, as measured in the narrowest of ways through traditional GDP, economic value-added and employment statistics.

Does this mean growth at any cost is good?

Clearly not. Nor is “green growth” alone necessarily desirable when viewed through any number of other lenses. The rapid deployment of low-carbon energy and other climate technologies does not guarantee inclusive growth, decent work, better health, less poverty or any number of other important global policy priorities.

“Affordable and clean energy” represents only one of 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals for good reason.

Nor is deploying more clean energy sufficient even as a climate solution. Energy-efficiency measures also have an important role to play, which is why the IRA, for example, includes a “High-Efficiency Electric Home Rebate Program.” Better-insulated buildings and more efficient modes of transportation would contribute to reducing carbon emissions long before energy and electricity are fully decarbonized. That is to say, efficiency cuts carbon pollution.

Better insulation also improves quality of life, by adding protection against wildfire smoke and other outdoor air pollution. Preventing toxic seepage into one’s home through poorly insulated windows, doors and walls improves human health, electricity bills and the value of real estate all at the same time.

True, this juxtaposition of clean energy growth on the one hand and efficiency measures on the other appears to mirror the “green growth” versus “degrowth” camps, but this is an illusion. Efficiency means doing more with less, which makes it effectively synonymous with economic productivity, one of the key ingredients in standard macroeconomic growth models.

This semantic point cuts both ways. There are developing nations in the Global South and specific regions in advanced economies that remain heavily dependent on extracting and exporting fossil fuels. These sectors and economies would necessarily shrink, as the rest of the world makes the transition to cleaner sources of energy and they might well end up poorer and more destabilized, but this is not what most advocates of degrowth have in mind.

Yes, some companies and individuals have profited massively from exploiting the planet’s resources, lobbying policymakers and covering up the damage they have done. That, in many ways, is where the motivation behind much “degrowth” thinking arises. We can all point to specific activities that we would rather see less of, but the question then is about framing and strategy.

I believe the productive path forward is to focus on the trillion-dollar business opportunity that rapid decarbonization presents and the many positive stories of transformation that go with it.

In the end, there is a fine balance to strike between unleashing the entrepreneurial “can-do” spirit and channeling it in the right direction — between Silicon Valley’s mantra of “move fast and break things,” and the physician’s oath of “first, do no harm.”

The latter, of course, goes hand in hand with paying for one’s own pollution. That pollution ought to be the true foil, rather than the economic growth that results from entrepreneurs, businesses and governments attempting to rein it in.

Gernot Wagner is a climate economist at Columbia Business School.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

US President Donald Trump is systematically dismantling the network of multilateral institutions, organizations and agreements that have helped prevent a third world war for more than 70 years. Yet many governments are twisting themselves into knots trying to downplay his actions, insisting that things are not as they seem and that even if they are, confronting the menace in the White House simply is not an option. Disagreement must be carefully disguised to avoid provoking his wrath. For the British political establishment, the convenient excuse is the need to preserve the UK’s “special relationship” with the US. Following their White House

Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention. If it makes headlines, it is because China wants to invade. Yet, those who find their way here by some twist of fate often fall in love. If you ask them why, some cite numbers showing it is one of the freest and safest countries in the world. Others talk about something harder to name: The quiet order of queues, the shared umbrellas for anyone caught in the rain, the way people stand so elderly riders can sit, the

After the coup in Burma in 2021, the country’s decades-long armed conflict escalated into a full-scale war. On one side was the Burmese army; large, well-equipped, and funded by China, supported with weapons, including airplanes and helicopters from China and Russia. On the other side were the pro-democracy forces, composed of countless small ethnic resistance armies. The military junta cut off electricity, phone and cell service, and the Internet in most of the country, leaving resistance forces isolated from the outside world and making it difficult for the various armies to coordinate with one another. Despite being severely outnumbered and

After the confrontation between US President Donald Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy on Friday last week, John Bolton, Trump’s former national security adviser, discussed this shocking event in an interview. Describing it as a disaster “not only for Ukraine, but also for the US,” Bolton added: “If I were in Taiwan, I would be very worried right now.” Indeed, Taiwanese have been observing — and discussing — this jarring clash as a foreboding signal. Pro-China commentators largely view it as further evidence that the US is an unreliable ally and that Taiwan would be better off integrating more deeply into