The mother of five knew something was wrong with the rain. The windows of her home in the Libyan city of Derna had started leaking, and when she opened them she saw a wall of water sweeping away screaming children and adults. Floating debris killed people in its path.

The deluge that tore through eastern Libya in the early hours of Sept. 11 eventually tore down half of the woman’s two-story building. She took refuge on the rooftop alongside her husband and children. She described the ordeal of watching the rising waters in an interview with Bloomberg Green, requesting that her name not be made public for fear of repercussions from Libyan authorities.

“From 3 to 4am the flood kept on and on,” the woman said. “We kept praying for the sun to be up and it just wouldn’t. It was the longest night of my life.”

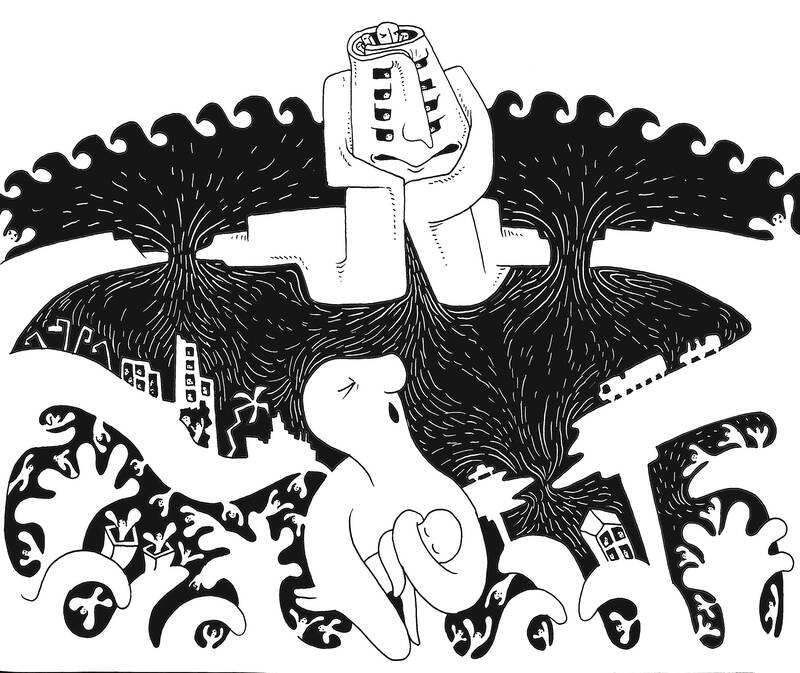

Illustration: Mountain People

The family survived and eventually fled to the eastern city of Ajdabiya.

More than 5,000 Libyans died in the flood and more than 10,000 remain missing, the UN said. So many people ended up dragged by the torrent of mud — the populations of entire buildings, in some cases — that dead bodies continued washing ashore days later.

Political instability, a decade of civil war, crumbling infrastructure and weak emergency systems all played a role in the tragedy that unfolded in the eastern region of Jabal al Akhdar. Add climate change to the mix, and the result is the deadliest and costliest storm ever recorded in the Mediterranean region.

“Many of the world’s challenges coalesced in an awful hellscape,” UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres told global leaders during his address to the General Assembly on Tuesday last week. Libyans “were victims many times over — victims of years of conflict, of climate chaos, of leaders far and near who failed to find a way to peace.”

All these issues will continue to weigh on Libya’s recovery from a climate-amplified disaster and likely make it harder for the country to prepare for the higher temperatures, drought and extreme rain to come. The fragile state of the country’s institutions make it difficult to tap into the pool of climate-relief money, even as more support becomes available through international programs. Last year’s COP27 climate summit saw a historic breakthrough to create a loss-and-damage fund to assist poor countries battered by extreme weather. However, that fund is not active yet, and it is hard to identify ready sources of support in the aftermath of Libya’s biggest climate disaster.

Warming temperatures are going to hit the world’s less-stable societies with extreme force. Flooding has become more intense, with disasters unfolding more suddenly, in part because the atmosphere holds 7 percent more water vapor for every degree Celsius of warming. Libya, with its decrepit infrastructure, has already warmed by more than a degree since 1900. If greenhouse gas emissions remain unchanged, the country’s average temperatures would rise 2.2°C by 2050 and by 4°C at the end of the century.

“What happened in Derna is the kind of thing we’re going to see more and more in countries like Libya,” said Ciaran Donnelly, a senior vice president for crisis response at the International Rescue Committee, a nonprofit that helps people affected by humanitarian crises. “Fragile and in-conflict states are significantly more vulnerable to climate change, because of the deterioration of social services and lack of maintenance of infrastructure.”

Forecasters spotted the danger to Libya three days in advance as the same storm wreaked havoc on Greece — but days of anticipation did not prevent disaster. Survivors reported getting contradictory alerts from different authorities in the hours before the storm. That confusion stems in part from Libya’s two governments — one in the east, one in the west — whose ongoing dispute meant there was no coordinated emergency preparation. There was no evacuation for the population along the Wadi Derna, a river that runs through the coastal city of Derna before flowing into the Mediterranean.

“It is not clear to what extent forecasts and warnings were communicated and received by the general public or relevant emergency responders,” said Maja Vahlberg, a climate-risk consultant with the Climate Centre, which works with the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement. “That meant anyone in the path of the water was at risk, not just those who are typically highly vulnerable.”

That marked the first failure. Next came the dams. The two-story-high wall of water that swept through city was not just the result of the heavy rainfall. A pair of dams made from clay, rocks and earth in the 1970s collapsed in the storm. Like much of Libya’s infrastructure, the dams on the Wadi Derna had been neglected for decades.

The world’s large number of aging dams, built to withstand a climate that no longer exists, would become an increasingly widespread problem, particularly in developing countries with few resources for upkeep. A detailed analysis of more than 35,000 dams published earlier this year in the journal Nature found the median year of construction globally was 1974. North America is home to the oldest dams, with the median year of completion of 1963, and Europe is next at 1966.

Reports of major cracks on the dams that failed near Derna date back to at least 1998, Libya’s general prosecutor said in a televised press conference on Sept. 15. The government of then-Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi, who ruled the nation in a dictatorship for 30 years, awarded a repair and maintenance contract to a Turkish company in 2007. Because of payment issues, work did not start until 2010 and abruptly stopped less than five months later, in 2011, during the popular uprising that toppled Qaddafi.

None of the successive governments resumed maintenance.

“Those dams have had cracks and issues since the last regime, and despite all the budgets and all the demands and the calls, nothing was done,” said Nermin al-Sherif, head of the Libyan General Federation of Trade Unions. “Climate change is not something that we just heard about. It’s an existential threat and a lot of mistakes were committed here.”

While Libya’s case is extreme, the country is not alone in its vulnerability to climate impacts. By the end of this decade the extent of urban land exposed to frequent flooding is projected to increase by about 270 percent in north Africa, by 800 percent in southern Africa and by 2,600 percent in the middle of the continent compared with levels at the turn of the millennium, the latest report from scientists on the UN-backed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said. About 70 percent of African cities are rated highly vulnerable to climate shocks.

Behind it all is the lack of critical infrastructure and the poor maintenance of old, often crumbling dams, bridges and roads. Adapting that infrastructure to extreme weather events made worse by climate change is a challenge for both developed and developing nations, but it is far tougher for poor countries that are often struggling with instability and have far greater difficulty accessing money.

Climate experts describe efforts to defend people from the destructive brunt of warming as “adaptation,” in contrast to “mitigation” efforts that curb planet-warming emissions. The world does not spend enough on either category. While poor nations have had trouble getting enough funding for mitigation, programs to finance adaptation have until recently been all but nonexistent.

That is starting to change. Adaptation finance flows to developing nations have been increasing even though the pace is still too slow, the UN Environment Programme’s Adaptation Gap Report for 2022 said.

Spending on adaptation in developing countries reached US$29 billion in 2020, far below the estimated needs of as much as US$340 billion by 2030 and up to US$565 billion by mid-century.

However, even that pool of funds is largely out of reach for Libya, which the UN portrays as a nation “severely constrained by conflict, political division and widespread impunity, compounded by fragmentation of government and governance structures, a bloated and inefficient civil service, systemic corruption, and weak transparency and accountability.”

In other words: not the sort of place where donor nations are willing to send money for public works.

Libya is one of the few signatories of the 2015 Paris Agreement that has never submitted a climate plan to the UN. These documents, known as Nationally Determined Contributions, or NDCs, outline countries’ vulnerabilities to climate change, as well as their plans to reduce the greenhouse gasses that cause it. Completing an NDC is a necessary step toward showing international donors where climate funds will be spent.

“The reality is that, for countries like Libya, it’s quite challenging to access the growing levels of climate financing available,” Donnelly said. “The comfort zone for international financial institutions is to work with administrations that are stable, and that’s often not the case in many of the countries most affected by conflict and fragility.”

Libya stands out in other ways. Many of the poorest and most climate vulnerable countries have relatively small emissions. Not so for Libya, home to Africa’s largest proven oil reserves and the highest emissions per capita on the continent. This means that the poor state of Libyan infrastructure results in frequent leaks of methane, a super powerful greenhouse gas, from the domestic oil and gas industry.

In this way, Libya’s shaky infrastructure can be viewed as a double threat. Global warming supercharged the storm that wrecked the country, making it up to 50 times more likely to happen and increasing its intensity enough to overwhelm aging dams, a report by World Weather Attribution (WWA) said. And, in a feedback loop, Libya’s leaking energy infrastructure also made a contribution to those rising temperatures.

“We found that climate change did make the rainfall more intense,” said Friedrike Otto, one of the report’s authors and cofounder of WWA, a group that rapidly analyzes weather data after natural disasters. “But also exposure to vulnerability and compounding disasters played a very key role.”

The storm wiped off a quarter of Derna and split the city in two. Many roads remain flooded, and the few left are crowded with people trying to leave or enter the region. Eastern and western authorities in Libya are setting up checkpoints on roads, and different authorizations are needed to move from one side to the other. Over the days following the storm, aid started trickling into Derna. Hundreds of civilians traveled to the affected areas to volunteer in search and rescue tasks. In an initial sign of some cooperation after the tragedy, Libya’s rival governments pledged 2 billion dinars (US$408 million) in assistance.

“Our people have set an example through their solidarity and its unity. It is time for democracy to begin in Libya,” Libyan Minister of Youth Fatahallah al-Zunni said in an address to the UN on Wednesday. “All of the sites of conflict that were spurred on by adverse conditions, all of this has been carried away by the torrents.”

However, in the nearly two weeks since the tragedy, there are signs that any hopeful mood has already soured.

Protests erupted in Derna on Sept. 18, as survivors raged over the lack of preparation and response to the storm, eventually touching the home of the city’s mayor. Shortly after, officials in the east ordered the removal of the entire city council, put Derna under military rule, and ordered local and foreign journalists to leave for allegedly impeding rescue operations, a statement by the Committee to Protect Journalists said.

Humanitarian organizations have been able to get supplies and personnel into the area so far, said Claire Nicolet, an emergency manager with Doctors Without Borders (MSF). However, she is worried that traveling freely across the country and the security of relief workers could become more challenging.

“There are signs that the door is starting to close,” she said, speaking from MSF’s headquarters in Paris.

On the ground in Derna, volunteers from elsewhere in Libya have started leaving. Families seeking survivors have given up. The chaos that followed the storm has faded, and the city has become quiet. Some small shops have reopened, MSF said.

For al-Sherif, the union leader who traveled to Derna as a volunteer to help victims of the flood, it is not the first time assisting in rescue efforts. During the decade-long war, she has helped people flee conflict. However, she said the eerie feeling of walking on debris with the fear of stepping on someone is new — and terrifying.

“Infrastructure was not maintained, cities were neglected, there was no proper planning and climate factors were not put into consideration,” al-Sherif said. “This should be a lesson to us and to the whole world.”