The military coup d’etat in Gabon on Aug. 30, which toppled the 55-year-long Bongo family reign, followed similar putsches by military officers that overthrew the largely elected civilian governments in Niger, Sudan, Burkina Faso, Mali, Guinea and Chad. Further dominoes might soon fall, with the harassment of opposition parties continuing in Senegal, Togo and Cameroon.

However, global powers like the US must understand the complex regional and external dynamics driving these coups so they can effectively respond to them. To defer to France’s hostile and interventionist approach would be too risky.

When four US soldiers were killed in a 2017 ambush in Niger, many Americans questioned what US troops were doing there. Twenty-four years earlier, then-US president Bill Clinton’s administration crippled UN peacekeeping in Africa after 18 US soldiers were killed in a similar ambush in Somalia, resulting in the withdrawal of US troops from the country amid cries of “No boots on the ground.” Next, former US president George W. Bush’s global “war on terror” was continued in Africa by former US president Barack Obama, who massively expanded the US’ presence on the continent. Obama established a military footprint in a dozen African countries, constructed drone bases in Djibouti, Ethiopia and Seychelles, and built a US$110 million drone and air base in Niger (which now stations 1,100 US troops).

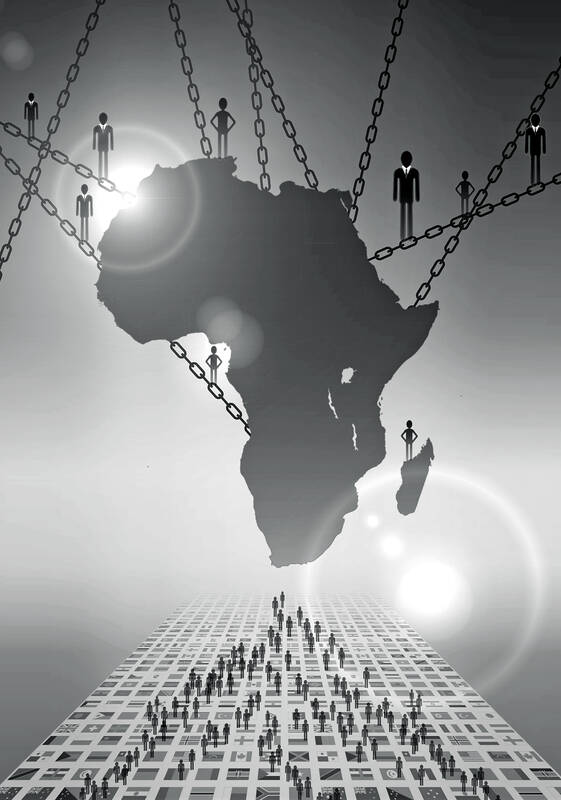

Illustration: Yusha

During the Niger coup, its former colonial overlord, France, had soldiers protecting uranium mines in the country’s north, continuing an exploitative pattern of Gallic companies monopolizing economic interests in its former colonies. Francafrique has a sordid relationship of corrupt political dealings and military agreements that have kept many dictators in power in countries like Gabon, the Central African Republic and Chad.

French leadership of the G5 Sahel countries — Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad and Mauritania — since 2013 has now spectacularly collapsed. The French military was expelled from its base in Mali, while military regimes in Burkina Faso and Guinea have become hostile to Paris. Many protesters across Africa’s French-speaking countries wave Russian flags in opposition to the former colonial power. The Russian mercenary group Wagner is currently assisting the military regime in Mali to battle militants, which governments in Niger and Burkina Faso are struggling to contain.

Understanding the regional dynamics of this conflict is essential. The 15-member Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has threatened the General Abdourahamane Tchiani-led putschists in Niger with a military intervention to restore deposed president Mohamed Bazoum to power — a position cautiously supported by Washington, who also fears the possible entry of Wagner mercenaries into Niger.

However, ECOWAS faces an existential crisis. It is currently split into four broad camps.

Nigerian President Bola Tinubu has so far lacked a sure touch in foreign policy. The poverty-stricken region suffers from US$100 billion of debt, exacerbated by the recent removal of a fuel subsidy that had kept domestic oil prices low. Nigeria led praiseworthy interventions in Liberia and Sierra Leone in the 1990s, but its military has since struggled to contain domestic jihadists. Tinubu faces pressure from an anti-interventionist public and parliament, while the presence of the large Hausa ethnic group that has traded and interacted across the Nigeria-Niger border for centuries further complicates the potential invasion that he has championed.

The second group of “hawks” within ECOWAS includes the Republic of Cote d’Ivoire, Senegal, Ghana, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau and Benin; their civilian leaders fear coups by their own militaries. This group has rejected the Niger junta’s proposed three-year transition to civilian rule, with many opposition parties and citizens across these countries also against any regional military intervention.

The third group are “muddlers,” including Liberia, Sierra Leone, Togo and Cape Verde, some of which have expressed concerns about the viability of a successful intervention to restore Bazoum back into Nigerian presidential power. A fourth group of military putschists has seen governments in Mali and Burkina Faso — and more quietly Guinea — pledge military support to soldiers in Niger to confront any ECOWAS intervention. The African Union (AU) remains ambivalent toward any armed operation.

US policy also appears to be in disarray in Niger — despite US Secretary of State Antony Blinken describing the country as a “model of democracy” just six months ago. Washington has avoided the openly hostile French posture toward Niger’s military junta.

For now, the US must halt its traditional deference to Paris on Sahel matters to avoid being labeled “neocolonialists.” Any ECOWAS military intervention would be viewed as symbolizing a Franco-American Trojan horse to protect Western interests in Niger. Washington should instead strongly back regional mediation efforts by ECOWAS and the AU, as bolstered by the UN.

US President Joe Biden would be keen to avoid another Somalia-style military disaster in Niger, considering his tough re-election battle next year.

Adekeye Adebajo is a senior research fellow at the University of Pretoria’s Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship in South Africa.