Olga Kharlan, a Ukrainian saber fencing star, faced off this week against Anna Smirnova, a Russian, and roundly and fairly defeated her. The scandal is what happened next.

Like most Ukrainian athletes these days, Kharlan refused to shake hands with her Russian opponent, to show that Russia’s genocidal war of aggression cannot be ignored, even in sport. Kharlan held out her blade instead, inviting Smirnova to tap it — a gesture that substituted for a handshake during the COVID-19 pandemic and ought to suffice.

Smirnova, who in photographs seems to support Russia’s invasion, opted to turn the situation into theater. For 45 minutes, she stayed on the piste, eventually sitting on a chair provided for her. The International Fencing Federation was impressed — it disqualified Kharlan, and advanced Smirnova to the next round.

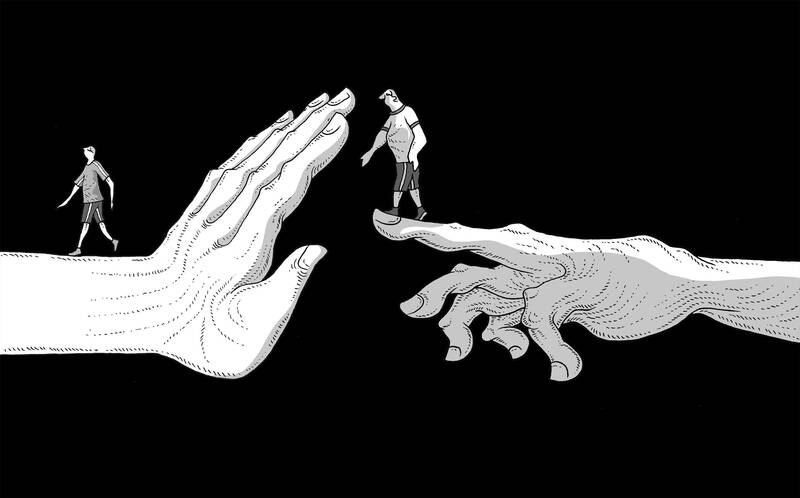

Illustration: Mountain People

This decision, whether technically justified or not, is outrageous.

“The soldiers of Russia are killing our people, the kids, stealing kids as well, kidnapping, so you cannot act normal,” said Elina Svitolina, a Ukrainian who is one of the world’s top tennis players, in support of Kharlan.

Svitolina, who comes from Odesa, which Russia has bombed with ferocity in recent weeks, also refuses to shake hands with her Russian and Belarusian opponents.

Sport, it has often been said, is humanity’s way to sublimate violent conflict — “war without shooting,” as George Orwell put it. Events like the Olympics are meant to transcend politics, but can sports — or anything, really — ever really be apolitical, or amoral?

As Svitolina points out, Russia and Belarus — like the Soviet Union during the Cold War and other countries — use their athletes as part of their propaganda. The same is often true of artists and other cultural ambassadors. That is why the Munich Philharmonic fired its celebrity conductor, Valery Gergiev, for example. Gergiev is Russian and he refused to condemn the invasion launched by his friend, Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Nationality alone, of course, must never become a moral label or verdict on an individual. That is a basic principle of liberalism as well as intuitive fairness. Collective punishment — what the Germans vividly call sippenhaft, “clan liability” — is as vile as the atrocities a clan may have committed.

Ukraine acknowledges this logic. After Russia’s invasion, it prohibited athletes representing Ukraine as a nation from competing against Russians. Some had to sit out tournaments in judo, wrestling, chess and other sports. However, just before Kharlan and Smirnova were to draw sabers, Ukraine changed its policy. Now its athletes are only barred from facing opponents who represent Russia or Belarus, not those of their citizens who, like Smirnova, compete as individuals.

This feels right. It is also why nobody, in Ukraine or anywhere, should shun the members of the punk band Pussy Riot, tennis player Andrei Rublev, or any Russian who does speak out against Putin’s aggression and atrocities. On the contrary, in dictatorships conscientious opposition to your own government requires extraordinary courage, and deserves respect.

Lack of such valor, however all-too-human, does not absolve anybody, though, in Russia today or anywhere at any time. When the US denazified their sector of West Germany after the Third Reich, they distinguished among major offenders, offenders, lesser offenders, followers and the exonerated. Only the minority in the latter group could honestly say they had done the right thing. By contrast, the huge numbers of followers — mitlaufer, literally those who “run alongside” — shared a special form of guilt, because they enabled the evil committed by others.

Nobody can therefore blame Holocaust survivors or other victims of the Nazis for refusing to shake the hand of a German mitlaufer. In the same way, nobody — and certainly not the International Fencing Federation — has the right to censure, disqualify or otherwise frown on Ukrainians today who refuse to shake hands with Russians.

As a gesture, shaking hands is a recent phenomenon in human history. It probably evolved as a way of demonstrating peaceful intentions, by extending a right hand that was not holding a weapon, or as a sign of forming a bond by clasping. Ukrainian athletes should be forgiven for finding neither symbolism fitting, as Russians bomb and terrorize their friends and relatives at home.

The person who should have been disqualified, if she had not already been defeated, was Smirnova, for making a spectacle out of the conviction and integrity of her opponent.

This week “we realized that the country that terrorizes our country, our people, our families, also terrorizes sports,” Kharlan later said. “I didn’t want to shake this athlete’s hand, and I acted with my heart.”

In my book, that is its own kind of victory.

Andreas Kluth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering US diplomacy, national security and geopolitics. A former editor in chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for The Economist, he is author of Hannibal and Me. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

The saga of Sarah Dzafce, the disgraced former Miss Finland, is far more significant than a mere beauty pageant controversy. It serves as a potent and painful contemporary lesson in global cultural ethics and the absolute necessity of racial respect. Her public career was instantly pulverized not by a lapse in judgement, but by a deliberate act of racial hostility, the flames of which swiftly encircled the globe. The offensive action was simple, yet profoundly provocative: a 15-second video in which Dzafce performed the infamous “slanted eyes” gesture — a crude, historically loaded caricature of East Asian features used in Western

Is a new foreign partner for Taiwan emerging in the Middle East? Last week, Taiwanese media reported that Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) secretly visited Israel, a country with whom Taiwan has long shared unofficial relations but which has approached those relations cautiously. In the wake of China’s implicit but clear support for Hamas and Iran in the wake of the October 2023 assault on Israel, Jerusalem’s calculus may be changing. Both small countries facing literal existential threats, Israel and Taiwan have much to gain from closer ties. In his recent op-ed for the Washington Post, President William

A stabbing attack inside and near two busy Taipei MRT stations on Friday evening shocked the nation and made headlines in many foreign and local news media, as such indiscriminate attacks are rare in Taiwan. Four people died, including the 27-year-old suspect, and 11 people sustained injuries. At Taipei Main Station, the suspect threw smoke grenades near two exits and fatally stabbed one person who tried to stop him. He later made his way to Eslite Spectrum Nanxi department store near Zhongshan MRT Station, where he threw more smoke grenades and fatally stabbed a person on a scooter by the roadside.

Taiwan-India relations appear to have been put on the back burner this year, including on Taiwan’s side. Geopolitical pressures have compelled both countries to recalibrate their priorities, even as their core security challenges remain unchanged. However, what is striking is the visible decline in the attention India once received from Taiwan. The absence of the annual Diwali celebrations for the Indian community and the lack of a commemoration marking the 30-year anniversary of the representative offices, the India Taipei Association and the Taipei Economic and Cultural Center, speak volumes and raise serious questions about whether Taiwan still has a coherent India