In a city that is constantly changing, some residents are pushing back.

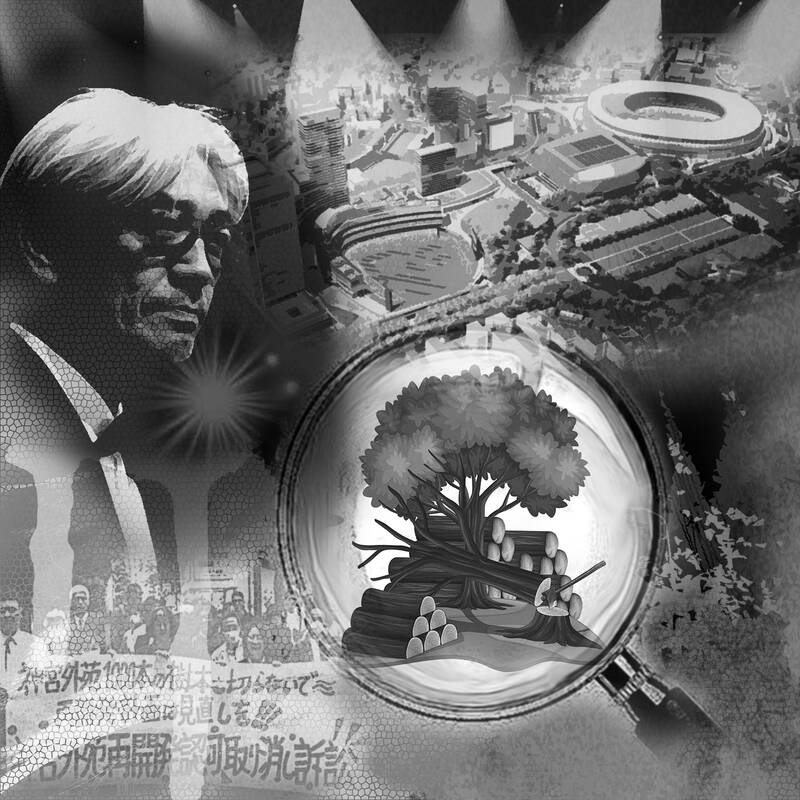

Plans to redevelop Jingu Gaien, a century-old park and sports center in central Tokyo, have met with stiff opposition from concerned citizens. In one of his final acts before his death in March, composer Ryuichi Sakamoto wrote to the governor opposing it.

Haruki Murakami, Japan’s most famous novelist, has spoken out against it, warning “once something is destroyed, it can never be restored.”

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

The 1.31km2 area is home to the Yakult Swallows baseball team, the city’s rugby pitch and about 2,000 trees, most notably a 300m row of gingko trees that is an unmistakable Tokyo landmark. In a joint project between Mitsui Fudosan Co, Itochu Corp, the Japan Sports Council and the landowners of Meiji Shrine, the project envisions knocking down and rebuilding the baseball and rugby pitches, switching their locations and constructing two new skyscrapers, along with communal spaces.

Opponents who want to preserve the site are livid, accusing the developers of putting profit ahead of residents. The backlash has made international headlines, perhaps because it feeds into narratives of a concrete-covered Japan. Most resistance has focused on the 700 trees that would be felled for the redevelopment.

First, some facts: The famous row of trees (which is what most people envision when they think of the vegetation there) would be preserved in its current form, though activists worry about potential damage to their roots. While some others would be cut down, the developers have pledged to increase the total to 1,998 by the end of the project by transplanting some and adding newer ones. The entire amount of green space would increase to 30 percent from the current 25 percent. So why the uproar? Chopping trees creates an emotional narrative, especially in a city going through a recent heatwave. Tokyo could use more greenery to combat the heat-island effect, so even a temporary loss feels concerning. Some of it stems from a perceived lack of consultation, particularly with those who do not live in the area. The developers’ move to share more information feels a little belated and needs to continue throughout the construction, but part of it also seems to stem from opposition to any change. As the city ages, or maybe just due to social media impact, redevelopment plans appear to be attracting foes. It seems these days that every aging building is sparking a campaign to save it.

However, the capital’s one constant is its never-ending change. If New York is the city that never sleeps, then Tokyo is the city that never stays the same.

“In Japan, there is less a culture of preserving old buildings,” the world-famous architect Tadao Ando said in 2006. “Japanese architecture is traditionally based on wooden structures that need renovating on a regular basis. Of course, we have since adopted concrete, steel and other durable materials, so the need to rebuild is no longer the same. But old habits die hard.”

Ando’s work is a great example. He was speaking then of the Doujunkai Aoyama Apartments, a block of modernist dwellings built in the 1920s and demolished in 2003 to make way for Ando’s Omotesando Hills mall. Opposed at the time, it is now seen as a signature work by one of the country’s great designers, and has become a crucial element in converting Omotesando into what it is now famous for — an elegant area where high-end shopping and architecture meet, such as New York’s Fifth Avenue or London’s Bond Street.

It is this lack of sentimentality and attachment to the past that has made Tokyo the world’s greatest city, or at least the most functional. Western visitors arriving post-COVID-19 pandemic are stunned to see how the city just ... works. No housing crisis or rental market inflation. Public transport is so functional that a stoppage on Monday on the capital’s key train line was the country’s top news story.

Ando explained that what was most important “was to save not the building itself, but the impression it made on the landscape.”

Tokyo’s best redevelopments do just that. Cries went up in 2015 over the redevelopment of the Hotel Okura; few complain anymore, as the new hotel is not only gorgeous, but keeps the feel of the original’s lobby, famously featured in a James Bond novel. In the 2000s, there was an outcry over the overhaul of the Shimokitazawa area; that has been a success, only improving on the area’s hipster charm. Disapproval would likely happen when the Imperial Hotel is torn down and rebuilt, beginning next year. (US architect Frank Lloyd Wright famously designed an earlier incarnation of the hotel before it was demolished in the late 1960s and replaced with the current version.)

Others mourn the loss of an iconic baseball field where Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig once played, worrying the change would drive fans away. The fears seem overblown. I lived in Hiroshima during the last years of the Hiroshima Carp’s beloved Municipal Stadium, located near the city’s famous Peace Park, before it was replaced by a new stadium elsewhere in the city. There was much upset then too, but the results are clear: Not only has the surrounding area been transformed, but average attendance at games has nearly doubled despite the stadiums having similar capacity. The Swallows’ ground is not without its charms, but it requires considerable modernization. Fitting with Ando’s philosophy, designs for the new stadium show they would preserve the feel of the existing facility, rather than creating a roofed field that would likely be more profitable.

Parts of the Jingu development do not seem perfect: I question the choice of an all-weather covered rugby stadium, even if it would become a venue for concerts, and I will mourn the loss of the grungy public batting center, which is not being replaced.

Residents being involved in these discussions is a good thing, but people should not veer from keeping developers honest to the not-in-my back-yard provincialism that has paralyzed so many Western cities, so rooted in the past they are unable to move into the present — think of the planning concerns that have choked homebuilding in the UK and elsewhere, even amid a housing crisis. Nor should people fall victim to the narrative of an inevitable decline — the idea that because of its aging and decreasing population Japan needs no more buildings: New places, ideas and even areas create an energy that refutes this assumption. Tokyo’s stock of incredible buildings and world-class public transport are only possible precisely because of its commitment to constant rebirth. Its beauty lies in the fact that it is ever-changing.

Gearoid Reidy is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Japan and the Koreas. He previously led the breaking news team in North Asia and was the Tokyo deputy bureau chief. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Trying to force a partnership between Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) and Intel Corp would be a wildly complex ordeal. Already, the reported request from the Trump administration for TSMC to take a controlling stake in Intel’s US factories is facing valid questions about feasibility from all sides. Washington would likely not support a foreign company operating Intel’s domestic factories, Reuters reported — just look at how that is going over in the steel sector. Meanwhile, many in Taiwan are concerned about the company being forced to transfer its bleeding-edge tech capabilities and give up its strategic advantage. This is especially

US President Donald Trump last week announced plans to impose reciprocal tariffs on eight countries. As Taiwan, a key hub for semiconductor manufacturing, is among them, the policy would significantly affect the country. In response, Minister of Economic Affairs J.W. Kuo (郭智輝) dispatched two officials to the US for negotiations, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC) board of directors convened its first-ever meeting in the US. Those developments highlight how the US’ unstable trade policies are posing a growing threat to Taiwan. Can the US truly gain an advantage in chip manufacturing by reversing trade liberalization? Is it realistic to

The US Department of State has removed the phrase “we do not support Taiwan independence” in its updated Taiwan-US relations fact sheet, which instead iterates that “we expect cross-strait differences to be resolved by peaceful means, free from coercion, in a manner acceptable to the people on both sides of the Strait.” This shows a tougher stance rejecting China’s false claims of sovereignty over Taiwan. Since switching formal diplomatic recognition from the Republic of China to the People’s Republic of China in 1979, the US government has continually indicated that it “does not support Taiwan independence.” The phrase was removed in 2022

US President Donald Trump’s second administration has gotten off to a fast start with a blizzard of initiatives focused on domestic commitments made during his campaign. His tariff-based approach to re-ordering global trade in a manner more favorable to the United States appears to be in its infancy, but the significant scale and scope are undeniable. That said, while China looms largest on the list of national security challenges, to date we have heard little from the administration, bar the 10 percent tariffs directed at China, on specific priorities vis-a-vis China. The Congressional hearings for President Trump’s cabinet have, so far,