I witnessed a spectacular row in a beer garden this summer. My fellow voyeurs and I guessed the couple were on a date — not their first, but perhaps their second or third — and he had checked his notifications too often for her liking.

“Why don’t you just date your phone instead?” she snapped, standing up to leave. “Hope you’re happy together.”

I have edited out a few F-bombs, but that was the gist. Sadly, she drained her drink rather than sloshing it in his face. Reader, I nearly stood up and applauded.

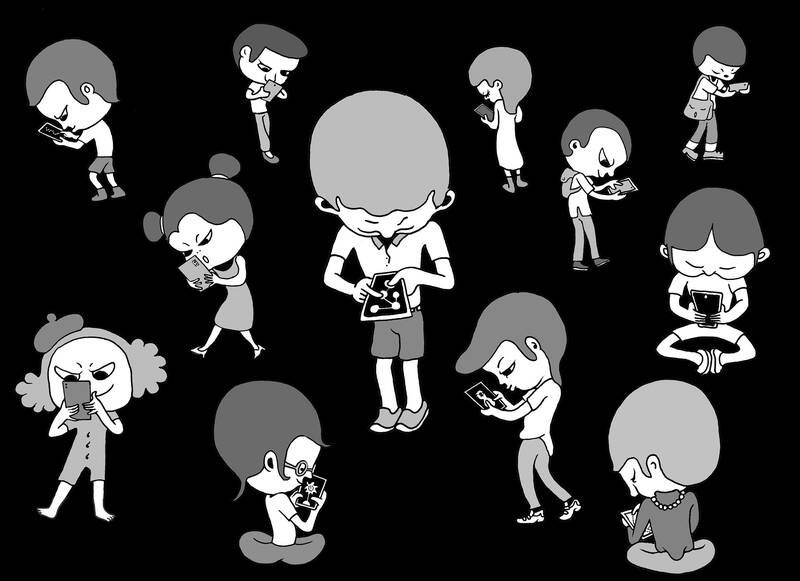

Illustration: Mountain People

“Phubbing” — a portmanteau of “phone snubbing,” or deciding to interact with your mobile phone rather than a person — is a 21st-century epidemic.

Last week, scientists confirmed, as they often do, what we already knew — that phubbing is bad for relationships.

Well, duh.

The study warned that it could even cost you your marriage. Couples who frequently phub experience more marital dissatisfaction. If your husband is a phubbee or your wife is a phone widow, beware.

“When individuals perceive that their partners are phubbing, they feel more conflict and less intimacy,” researchers from Nigde Omer Halisdemir University in Turkey said. “People should be mindful about being present with their loved ones to show they care and put their phone away.”

Amen, my white-coated friends.

I cannot bear being phubbed. The habit is not just rude, it sends a message that actual people matter less than digital ones. You are effectively saying that non-urgent e-mails and the latest Twitter spat are more interesting than a “catch up” with that valued pal you see twice a year. Sorry mate, was my amusing anecdote keeping you from liking Instagram pictures of sunsets?

The ultimate phubbing insult is watching videos or browsing TikTok with the sound up. A friendship-ending offense, frankly.

I am accustomed to being phubbed by my children. Born in the era of smartphones, online gaming and social media, they are part of the “grunt a reply without even looking up” generation. To maintain sanity, we have a strict screen curfew and ban at mealtimes. It is a matter of manners. Boundaries. Standards. Other words that infuriate youngsters.

From partners or peers, phubbing is less forgivable. The average person spends 3 hours, 23 minutes a day on their phone and checks it 58 times. It has become a buzzing, beeping comfort blanket. If you must have it to hand, at least keep it face down out of courtesy. Besides, you can always peep when they nip to the toilet.

When is it OK to phub?

Perhaps when you arrive early at a large meeting and there is a tacit agreement to swerve small talk until everyone arrives. In social situations, only phub for the communal good. This might include finding a funny meme, looking up a fondly remembered recipe or confirming a celebrity’s age, height, whether they are still alive.

When is it not OK?

During dates, mealtimes, work appraisals, weddings, funerals and sex.

There are polite ways to phub. See the old: “Sorry, I’ve got to take this” gesture, or the classic mouthed apology and eye roll in mid-phone conversation. If you must phub, explain why and keep it short.

Awaiting communication from a family member or crucial work news? Fine.

Checking in on the latest Love Island recoupling? Not fine.

A midweek soccer match not involving your team does not qualify, despite how the TV station hypes it up. Be honest and don’t lie about it. I call this “phibbing.”

It also raises the question of what we did in the dark days before mobile phones. Hide behind the newspaper like a grumpy dad? Retreat to the kitchen or garden shed to “potter” (i.e. get some peace and quiet)?

Maybe we stared blankly into space until somebody said “penny for them,” or clicked their fingers in front of our face to snap us out of it. Those people can phub right off.

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while

The military is conducting its annual Han Kuang exercises in phases. The minister of national defense recently said that this year’s scenarios would simulate defending the nation against possible actions the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) might take in an invasion of Taiwan, making the threat of a speculated Chinese invasion in 2027 a heated agenda item again. That year, also referred to as the “Davidson window,” is named after then-US Indo-Pacific Command Admiral Philip Davidson, who in 2021 warned that Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) had instructed the PLA to be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. Xi in 2017