Drought in Spain, which is experiencing yet another heat wave this year, is so extreme that virtually no aspect of daily life has been left untouched.

Dishes are left unwashed overnight when water allowances run out. Cows raised for gourmet meat risk going thirsty. Tourists heading to a water sports destination are met with hard mud. These stark scenes are taking place as Europe endures its driest period in at least 500 years, a situation that has been made more likely — and worse — by climate change.

“We had light rains toward the end of May and in June that helped the agriculture sector and lowered wildfire risk,” Catalan meteorological agency director Sarai Sarroca says. “But nothing to the scale of what we need to alleviate 34 straight months of drought.”

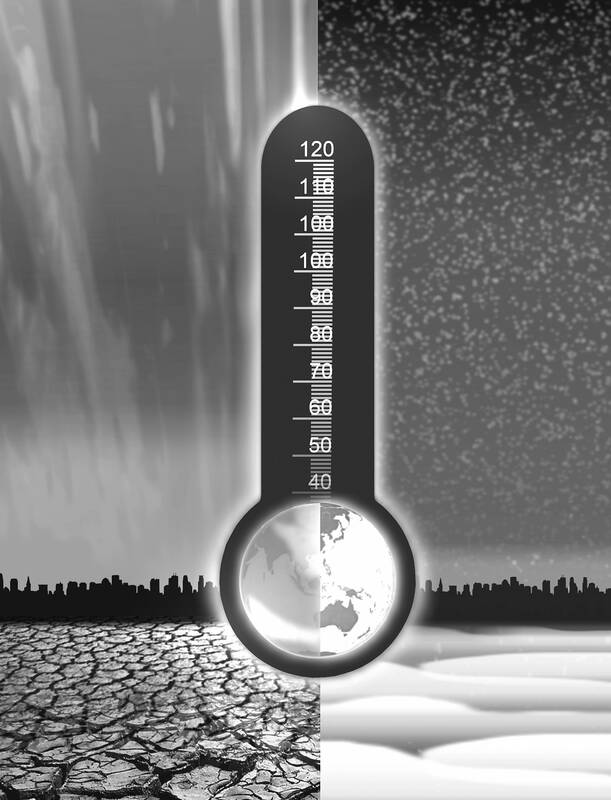

Illustration: Yusha

Greenhouse gases emitted from human activities have warmed the planet 1.2°C since pre-industrial times on average. However, Europe is warming at least twice as fast, and Catalonia even more so, with temperatures 2.7°C higher in 2022 than the average between 1960 and 1990, the meteorological agency said.

This week parts of Spain have been facing a severe heat wave, with the national weather forecasting agency Aemet issuing an “extreme risk” alert for the southern region of Andalusia on Wednesday.

In Catalonia, the heat, along with historically low rainfall levels, has left reservoirs in a dire state. They are at just 30 percent of their capacity, below the average of 46.5 percent for the whole of Spain.

North of the metropolitan region of Barcelona, home to over 3 million people, is the Sau reservoir. It was created in the 1960s by flooding Sant Roma de Sau, a village dating back to the 10th century. For decades, the sight of the former village’s Romanic church bell tower peeking from the waters was an easy indication of whether levels were high or low. Today, the entire building sits exposed, bone dry, surrounded by scorched mud.

In February, the Sau reservoir had so little water that authorities grew concerned it would mix with the mud at the bottom, depleting oxygen levels and killing the fish living in the basin. If that happened, what little water that was left would be unfit for human consumption. So the Catalan government hired fishermen to capture and destroy 4,000 fish to prevent them from contaminating the supply. The remaining water was salvaged by transferring it to a second reservoir nearby.

By April, water levels at Sau had dropped to just 6.5 percent. The surface area that was covered by water was so small that firefighting planes would be unable to collect water if they were called into service to extinguish wildfires in the summer. Two other reservoirs in the region are in similarly poor shape, so firefighters are searching for alternatives as they prepare for the wildfire season.

On weekends, dozens, sometimes hundreds, of people have driven through the narrow roads that lead to the reservoir to snap selfies against the striking landscape — the rocky cliffs, muddy puddles of water and ruins of the old village. Tourists have caused traffic jams that hinder the work of officials tasked with monitoring water quality. A couple of times, visitors got stuck on the muddy shores, which prompted the government to consider restrictions on entry to the reservoir.

“People like to see misfortune,” says Albert Pladevall, the owner of a small kayaking business that operates in Sau. “Down there in the cities they might be worried about drought, but they open the tap and water comes out of it.”

For years, Pladevall guided visitors through the reservoir’s waters so they could row around the church bell — always a crowd-pleaser. Earlier this year, the government banned water activities for months to limit the amount of people in the area.

On June 26, local businesses, including Pladevall’s, were allowed to reopen amid warnings that they would go broke.

“Everything is very uncertain,” says Pladevall, who worries the rains of the past few weeks offer little relief over the long term. “If the drought keeps on going, we’ll have to reinvent ourselves somehow.”

The impacts continue downstream. A local hotel that used to pump water directly from the Sau reservoir now must buy it from trucks — an expense that threatens its survival. The nearby village of Vilanova de Sau, home to about 300 people, is pumping water from a stream nearby because quality levels in the reservoir remain low, mayor Joan Riera says.

Farmers are struggling too. Rafel Rodenas is one of a handful of cattle ranchers in Spain to raise Wagyu-certified beef, selling the meat directly to Michelin star-rated restaurants in the area. For the meat to maintain its certification, each of his 170 cows and two bulls need to drink between 70 and 100 liters of water per day, graze on pesticide-free grass that grows on rain and eat as little fodder as possible.

This year, the grass barely reached a few inches tall in the middle of spring, when it should have been about two feet high. That forced his cows to look for fresh grass inside the forest, where they usually only feed in the summer. Rains in May and June helped improve the situation, but Rodenas fears during the traditionally dry summer months he would have to feed them leaves cut directly from oak trees — an ancient trick that farmers in the region used to resort to in winter months. After that, his only plan is to hope for the best.

“The fields have no time to regenerate because of the lack of water,” Rodenas says. “The price of hay has increased fourfold and the worry is that we won’t find any during the summer because these crops depend on rain and in many farms they haven’t grown enough to harvest.”

Further away from the reservoirs, at least 80 villages this year have had their pipes turned off for most of the night, forcing them to depend on trucks that deliver water every morning. The controversial measure was implemented after realizing that air accumulates overnight in the increasingly empty pipes. As temperatures rise in the morning, that air expands, increasing the risk of pipes bursting and causing leaks.

In the village of L’Espluga de Francoli, where its 3,700 residents have no water from 10pm to 5am, Joana Perez has had to adapt. She keeps a stash of bottled water to keep the coffee machine running at the bar that she owns, and every day she fills up large buckets of water to ensure she has enough to refill the toilet tanks and do the dishes.

“It’s more expensive, but I’ve become used to it,” Perez says. “There’s nothing else we can do, really.”

Not far away is Bar Del Casal, which for decades has had a 1,500-liter tank. It used to come in handy the few times a year when there were one-off water cuts, owner Enric Sole says. Now it is the lifeline of a business operating from 8am to 1am, serving hundreds of meals and drinks every day.

“Even if we have a secure water supply, we are really careful about the water we use,” Soler says. “Just twice we ran out of water in the [tank] and had to leave the dirty dishes until the next day.”

Soler is also the owner of the village’s swimming pool bar, which opens only in summer, but does not have a tank. “We leave the dishes dirty until the next day — we close earlier at night and open earlier in the morning too.”

To use the little water that is left as wisely as possible, authorities have declared an emergency over half of Catalonia. The measures affect close to 500 villages, including Barcelona. They include shutting down decorative public fountains, bans on filling swimming pools and using drinking water to clean streets or buildings.

Barcelonians are used to water scarcity and authorities routinely run campaigns on how to save water. The Catalan government limits water use to 230 liters per person daily, a metric that includes industry, tourism and agriculture consumption. Households in Barcelona are keeping well within those restrictions. Water use in homes is about 103 liters per person per day — well below Spain’s average of 134.

The city has also started tapping its underground water reserves over the past few months. For the first time ever, that groundwater is being used to irrigate public gardens.

Every morning, large trucks fill up and deliver water to the city’s parks. Grass lawns have not been irrigated for months, but trees and bushes are fed using techniques such as drip irrigation. Their survival is needed to keep the city cool during the hottest months of the year. Over summer months, local authorities set up climate refuges in parks and public buildings, so people can cool off when the heat reaches dangerous levels.

Local authorities hope these measures would guarantee water supply for the whole population throughout the summer, but further restrictions could be put in place in autumn. In May and last month, rainfall delivered just over 200 liters per square meter, but at least the same amount is needed to truly alleviate the situation, Sarroca says.

Adding to the concerns is the El Nino phenomenon arising over the Pacific Ocean this year, altering weather patterns globally and bringing higher temperatures in the western Mediterranean. Globally, last month was the world’s hottest June in at least three decades, while the first week this month was the hottest ever.

“Two years of record heat in a row would be a catastrophe in this context of drought,” Sarroca says. “But it’s something we can’t rule out in this world dominated by climate change.”

With assistance from Rodrigo Orihuela.

Recently, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) hastily pushed amendments to the Act Governing the Allocation of Government Revenues and Expenditures (財政收支劃分法) through the Legislative Yuan, sparking widespread public concern. The legislative process was marked by opaque decisionmaking and expedited proceedings, raising alarms about its potential impact on the economy, national defense, and international standing. Those amendments prioritize short-term political gains at the expense of long-term national security and development. The amendments mandate that the central government transfer about NT$375.3 billion (US$11.47 billion) annually to local governments. While ostensibly aimed at enhancing local development, the lack

Former US president Jimmy Carter’s legacy regarding Taiwan is a complex tapestry woven with decisions that, while controversial, were instrumental in shaping the nation’s path and its enduring relationship with the US. As the world reflects on Carter’s life and his recent passing at the age of 100, his presidency marked a transformative era in Taiwan-US-China relations, particularly through the landmark decision in 1978 to formally recognize the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as the sole legal government of China, effectively derecognizing the Republic of China (ROC) based in Taiwan. That decision continues to influence geopolitical dynamics and Taiwan’s unique

Having enjoyed contributing regular essays to the Liberty Times and Taipei Times now for several years, I feel it is time to pull back. As some of my readers know, I have enjoyed a decades-long relationship with Taiwan. My most recent visit was just a few months ago, when I was invited to deliver a keynote speech at a major conference in Taipei. Unfortunately, my trip intersected with Double Ten celebrations, so I missed the opportunity to call on friends in government, as well as colleagues in the new AIT building, that replaced the old Xin-yi Road complex. I have

On New Year’s Day, it is customary to reflect on what the coming year might bring and how the past has brought about the current juncture. Just as Taiwan is preparing itself for what US president-elect Donald Trump’s second term would mean for its economy, national security and the cross-strait “status quo” this year, the passing of former US president Jimmy Carter on Monday at the age of 100 brought back painful memories of his 1978 decision to stop recognizing the Republic of China as the seat of China in favor of the People’s Republic of China. It is an