This year marks the 300th anniversary of the birth of Adam Smith, the founding father of modern economics. It comes at a time when the global economy faces several daunting challenges. Inflation rates are the highest since the late 1970s. Productivity growth across the West remains sluggish or stagnant. Low and middle-income countries are teetering on the brink of a debt crisis. Trade tensions are rising. And market concentration has increased among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries.

Against this backdrop, Smith’s tercentenary is an opportunity to reflect on his invaluable insights into the dynamics of economic growth and consider whether they can help us understand the current moment.

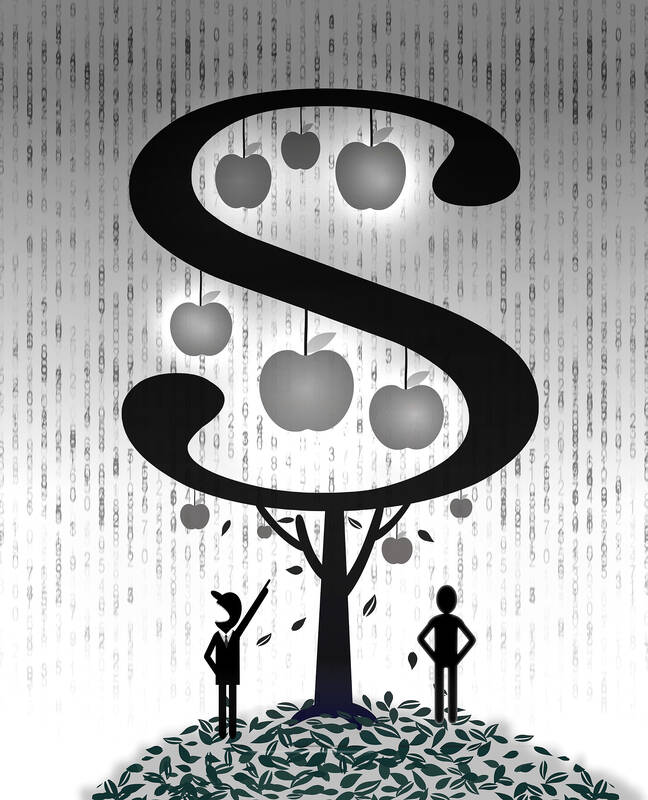

At the heart of Smith’s theory of economic growth, outlined in the first chapter of his seminal work The Wealth of Nations, is the specialization facilitated by the division of labor. By breaking down production into smaller tasks — a process illustrated by Smith’s famous example of the pin factory — industrialization enabled enormous gains in productivity.

Illustration: Yusha

However, this process is not confined to individual firms. Since the division of labor, according to Smith, is “limited by the extent of the market,” the market must expand through exchange. After all, boosting daily widget production from 100 to 10,000 is pointless if no one wants to buy widgets. So, the division of labor is a collective process that involves a continuous process of structural economic change. When there is a larger supply of affordable widgets, the widget-using sectors of the economy can expand production and reduce prices. Meanwhile, the market’s increased size would allow upstream suppliers of materials required to produce widgets to reorganize production into more specialized tasks.

As the US economist Allyn Young noted in 1928, this is a dynamic story of increasing returns. The growth process is a virtuous circle of structural change that starts slowly and then accelerates, like an avalanche. The Industrial Revolution and the rapid growth of East Asia’s “tiger” economies during the 1980s and 1990s are perfect examples of the process Smith identified. And yet, the stagnant growth that has plagued developed economies over the past decade raises the question of whether global progress toward what he described as “universal opulence” has ground to a halt.

Although the division of labor into specialized tasks has often enhanced the skills and expertise of workers, this might not always be the case. The emergence of generative artificial-intelligence models has fueled concerns that employers would use these technologies to deskill human workers and cut costs, prompting calls for regulatory interventions to ensure that AI augments, rather than replaces, human capabilities.

Moreover, while economic growth since the onset of the Industrial Revolution has led to astonishing advances in health and well-being, it is important to recognize that the institutional frameworks and political choices that enabled this progress were the result of intense social struggles.

Another concern that is often overlooked stems from market size. Smith would likely have been shocked by the extent of specialization in the 21st-century economy (and probably also pleased with his foresight). Today, manufacturing relies heavily on complex global production networks. Final products such as automobiles and smartphones comprise thousands of components manufactured in multiple countries. Many of the intermediate links in those supply chains are extraordinarily specialized. The Dutch company ASML, for example, is the only producer of the ultraviolet lithography machines needed to produce advanced chips, most of which are manufactured by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.

However, the widespread nature of this phenomenon suggests that the global market for many products can sustain only a few companies capable of achieving economies of scale. While this has long been the case for large manufacturers in sectors such as aerospace, it increasingly applies to smaller markets for intermediate components.

Consequently, Smith’s other condition for economic growth — the presence of competition — is not met. Competition helps to ensure that economic growth is socially beneficial, because it prevents firm owners from monopolizing the benefits of specialization and increased exchange.

As Smith put it in The Wealth of Nations, “[i]n general, if any branch of trade, or any division of labor, be advantageous to the public, the freer and more general the competition, it will always be the more so.”

Although the decline of competition has been a growing concern in Western economies over the past few years, the debate has largely focused on high-profile sectors within domestic markets, such as Big Tech. Policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic have responded to concentration in the tech industry with new laws, such as the EU’s Digital Markets Act, and tougher enforcement of existing antitrust laws, such as the US Federal Trade Commission’s recent decision to block Microsoft’s takeover of Activision.

However, the deeper policy question is whether the level of specialization in certain markets has reached a tipping point where there is a trade-off between Smith’s two prerequisites for growth. Has the division of labor reached its limit — and is the need to enhance competition therefore another reason to diversify supply chains and develop new sources of supply of production?

Diane Coyle, professor of public policy at the University of Cambridge, is the author, most recently, of Cogs and Monsters: What Economics Is, and What It Should Be (Princeton University Press, 2021).

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Why is Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) not a “happy camper” these days regarding Taiwan? Taiwanese have not become more “CCP friendly” in response to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) use of spies and graft by the United Front Work Department, intimidation conducted by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the Armed Police/Coast Guard, and endless subversive political warfare measures, including cyber-attacks, economic coercion, and diplomatic isolation. The percentage of Taiwanese that prefer the status quo or prefer moving towards independence continues to rise — 76 percent as of December last year. According to National Chengchi University (NCCU) polling, the Taiwanese

It would be absurd to claim to see a silver lining behind every US President Donald Trump cloud. Those clouds are too many, too dark and too dangerous. All the same, viewed from a domestic political perspective, there is a clear emerging UK upside to Trump’s efforts at crashing the post-Cold War order. It might even get a boost from Thursday’s Washington visit by British Prime Minister Keir Starmer. In July last year, when Starmer became prime minister, the Labour Party was rigidly on the defensive about Europe. Brexit was seen as an electorally unstable issue for a party whose priority

US President Donald Trump’s return to the White House has brought renewed scrutiny to the Taiwan-US semiconductor relationship with his claim that Taiwan “stole” the US chip business and threats of 100 percent tariffs on foreign-made processors. For Taiwanese and industry leaders, understanding those developments in their full context is crucial while maintaining a clear vision of Taiwan’s role in the global technology ecosystem. The assertion that Taiwan “stole” the US’ semiconductor industry fundamentally misunderstands the evolution of global technology manufacturing. Over the past four decades, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, led by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), has grown through legitimate means

US President Donald Trump is systematically dismantling the network of multilateral institutions, organizations and agreements that have helped prevent a third world war for more than 70 years. Yet many governments are twisting themselves into knots trying to downplay his actions, insisting that things are not as they seem and that even if they are, confronting the menace in the White House simply is not an option. Disagreement must be carefully disguised to avoid provoking his wrath. For the British political establishment, the convenient excuse is the need to preserve the UK’s “special relationship” with the US. Following their White House