Paper is the environmentally superior alternative to plastic. Except, what if it is not?

In a series of recent studies, researchers presented hundreds of shoppers with two granola bars and asked which is more environmentally friendly: the one in a plastic wrapper enclosed in an additional layer of paper, or an identical plastic-packaged bar, minus the paper. By a large margin, the research subjects chose the plastic-plus-paper option, despite that they both contained the same amount of plastic and the over-packaged granola bar is clearly far less environmentally friendly.

It is an understandable, if illogical, mistake. Plastic has become the world’s most vilified material, especially for single-use packaging. It is not only environmentally damaging; it has become socially unacceptable. Polling consistently finds that consumers want to see plastic replaced. Consumer product companies, hoping to shield their brands from the fury, are seeking sustainable solutions.

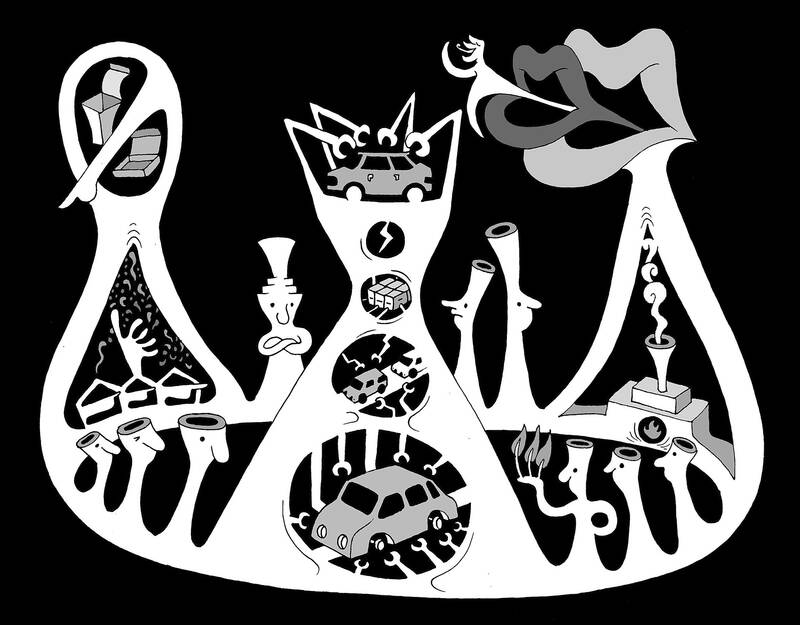

Illustration: Mountain People

Paper has become a favored alternative. Consumers see it as more “natural,” but it is not always the green choice that advocates seek — or claim. In some cases it can be worse than plastic.

For as long as humans have had the desire to move and preserve stuff, they have needed more and better packaging. The ancient Greeks manufactured ceramic wine vessels in bulk quantities and mid-century Americans bought convenient Ziploc bags by the billions, but whether in 1000 BC or 1970, packaging had to be cost-effective, easily transported and durable.

Over the past two decades, though, brands and consumers have begun demanding an entirely new property in their packages: Sustainability. It is an amorphous concept. For some, sustainability represents recyclability, while for others it suggests a commitment to reduce carbon emissions and combat climate change, but most agree on this, at least: Plastics do not qualify. Among other perceived problems, they are derived from petrochemicals, and they persist in the environment if not recycled or disposed of properly.

For many brands, the solution to the plastics-packaging revolt is to embrace paper as the natural alternative. There are ways to do this, some sincere and some not.

For example, many brands recognize that unbleached (brown) paper packaging (or packaging that looks unbleached) projects a natural, sustainable image to eco-conscious consumers — even when the product is being sold as single-use. Others attempt to boost their sustainable packaging credentials by replacing plastic with recyclable paper. For example, earlier this year Nestle SA piloted paper KitKat wrappers in Australia. It was an impressive technical feat, although one with limited impact. Nestle produces billions of KitKat’s annually; in Australia, it introduced “more than a quarter of a million” in paper wrappers.

Most of these paper solutions focus on what happens to a package after it is thrown into a waste or recycling bin, but end-of-life is not — and should not be — the most important sustainability benchmark. Other factors are arguably far more impactful. For example, what kinds of greenhouse emissions are associated with different packages? The answers often surprise.

A recent McKinsey & Co study of milk containers in the US found that paper cartons, which must be lined with plastic, generate 20 percent more greenhouse emissions over their lifecycles, from production to disposal, than plastic jugs. Other plastic packaging, from meat packages to shopping bags, showed similar to greater climate advantages over paper.

And even if a brand focuses on the end-of-life — or recyclability — aspect, there are complexities. Food-grade paper packaging is often lined by plastics that render packages unrecyclable, or they are only recyclable in a few locations. KitKat’s paper wrappers are lined by foil that the company touts as recyclable in Australia, but Nestle did not respond to a follow-up question as to whether and where they could be recycled in North America and Europe. If they are not recycled and they end up in landfills, they can become potent sources of methane, a greenhouse gas.

Meanwhile, plastic is not the recycling disaster that it is often portrayed to be. PET, the resin used in water and soda bottles, is highly recyclable and in high demand by manufacturers looking to make everything from carpets to new water bottles. Last year there were at least 180 plastics recyclers in the US handling PET and other resins.

However, there are also notable problems. Even if the packaging is technically recyclable, excess food scraps are often disqualifying, whether it is plastic or paper.

The raw material challenges are not confined to recycling and petrochemicals. The production of virgin papers for packaging has its own challenges, starting with the destruction of carbon-sequestering trees. As demand for paper packaging grows, who will supply the pulp? Sustainable forestry is a growing and important option, but consumers and brands will increasingly face questions about whether single-use paper packaging represents the best use for slow-growing resources. Consumers might decide that they do not and regulators might follow.

That does not mean paper packaging is unsustainable. Rather, like plastic, this seemingly natural material has environmental pluses and minuses of its own. Unfortunately, the highly emotive debate over ocean plastics has made it difficult and even unwise for brands to provide a nuanced explanation for their packaging choices. Instead, they must wrestle with how to reach consumers whose perceptions of sustainability have been repeatedly biased in favor of a less-than-perfect solution.

Rebalancing those perceptions, and laying the groundwork for an honest discussion about packaging sustainability will not be easy, but it must start with transparency. Brands with resources should voluntarily disclose the emissions associated with their packaging decisions, placing the number near the recycling symbol. To ensure the validity of those numbers, regulatory agencies should begin sketching out standards for calculating them.

These environmental “nutrition labels” could spur competition and innovation, benefiting consumers, the environment and brands alike. Even better, such labels might become a competitive incentive for brands to reduce their packaging altogether. If consumers learn to trust the labels, then “paper or plastic” becomes a less fraught question — it is only a matter of which material is more sustainable in that use case.

Complex problems rarely have simple solutions. Consumers, above all, must understand that complexity if they have any hope of achieving sustainability.

Adam Minter is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asia, technology and the environment.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion