When African Union members pledge to “continue to speak with one voice and act collectively to promote our common interests and positions in the international arena,” they recognize that this is not an easy feat. As with Rome, the “Africa we want” — the global powerhouse of the future — will not be built in a day.

Convening for the EU-African Union (AU) summit in Brussels this month, African and European leaders are to discuss how the partnership between their two unions can be both deepened and broadened.

However, when it comes to trade cooperation, the devil is in the details. The AU must heed the lessons (the successes and the failures) of the EU’s own integration project. Only then can it build a strong foundation for a partnership of equals with Europe.

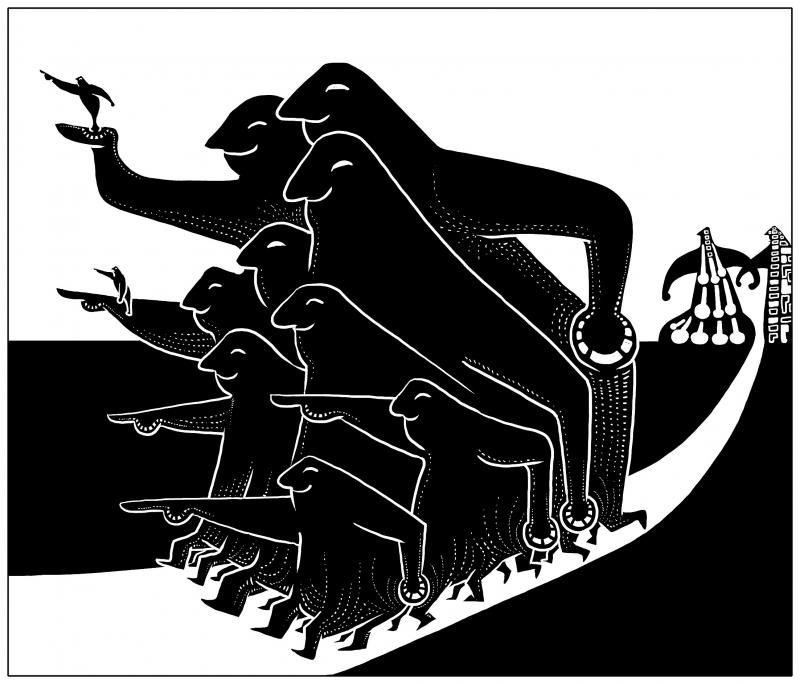

Illustration: Mountain People

The EU is a globally recognized model of regional partnership and integration.

Born from the ashes of war, suffering and destruction, it used economic integration to create the conditions for lasting peace and security.

It is now one of the world’s three largest trading powers, alongside the US and China.

Africa is taking promising steps along the same path. There has been impressive progress in expanding its regional economic communities (RECs) — country groupings designed to facilitate economic integration — and last month, the African Continental Free Trade Area entered into force. The hope now is that the free-trade zone will help lift millions of Africans out of extreme poverty by boosting growth, creating jobs and increasing incomes — while spurring the continent toward even deeper integration.

The AU and the EU, together and individually, must focus their efforts on the appropriate vehicles for attaining this goal. For its part, the AU would need to establish stronger institutions capable of nurturing economic growth and ensuring that its gains are widely shared. As recent coups in West Africa show, many African countries have a long way to go to establish good governance and provide for their populations.

This is where the EU’s own past experiences (the good and the bad) could prove useful, particularly when managing tensions between bilateral and multilateral initiatives. For example, the subsidiarity principle — whereby the EU takes charge of an issue only when supranational governance is clearly more effective than national, regional or local governance — has served the EU well.

How might Africa use this principle to strengthen relationships between RECs? One promising model, epitomized by the pan-European venture that created Airbus, is projects that tap into common economic interests. African projects in this mold could mitigate vulnerabilities in the continent’s value chains and industrial capabilities — shortcomings that the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted.

African countries can also make better use of individual RECs’ competitive advantages to shape strategic programs to manufacture products that can be fully sourced and assembled on the continent. For example, an African electric vehicle program could rely on aluminum from Guinea, technical parts from Rwanda, and assembly processes in Kenya or Morocco.

As for the EU, it must empower continent-wide bodies such as the AU and the African Development Bank to support sustainable integration programs.

China’s pledge last year to allocate US$10 billion to African financial institutions could be a catalyst for strengthening these institutions and uncovering more homegrown financing solutions.

Again, Africa can look to the EU’s own experience to improve how it allocates funding for regional integration, agriculture and infrastructure development.

However, the continent must be mindful of the EU’s own fragmented trade policy toward Africa. If African countries are trading with the EU on bilateral terms, that could undermine trade integration within Africa itself. It also weakens Africa’s ability to negotiate as a united bloc — “speaking with one voice.”

The EU-AU summit is an opportunity to consider vital questions about Africa’s economic future. Can Africans negotiate as one bloc, and will the EU commit to widening its cooperation beyond the traditionally aid-centered approach? Both questions are crucial, in part because Africa would need financing to support its climate mitigation and adaptation efforts alongside the project of regional integration.

When the AU sits down to negotiate with the EU, let us remember that achieving unity is a lengthy process, and that trade, development and cooperation are not smooth, easily managed processes.

There will likely be wrong turns, dead ends and accidents, but let us also remember that if Africans can speak as one, the EU-AU summit could take Africa further down the path of growth, prosperity and, ultimately, unity.

Malado Kaba, managing director of Faleme Conseil, served as the first female Guinean minister of economy and finance, and is a member of the Amujae Initiative at the Ellen Johnson Sirleaf Presidential Center for Women and Development.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its