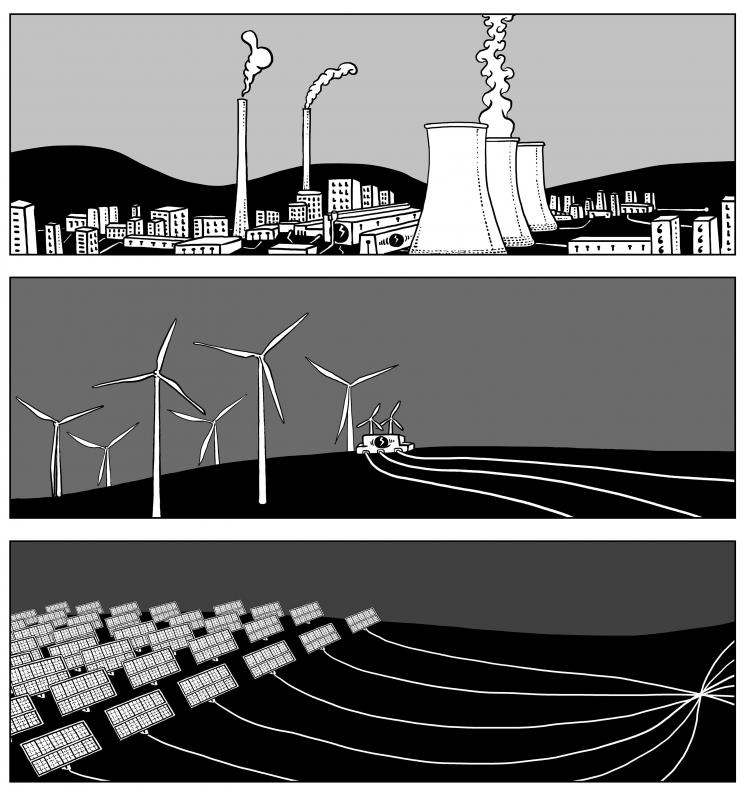

To turn wind and sunlight into power, first you need land. Lots of land, ideally unpopulated, where you can install hundreds of wind turbines and thousands of solar panels.

Bringing all that green power to densely populated commercial centers requires something else — thousands of kilometers of ultra-high voltage (UHV) power lines, audibly buzzing with electricity.

China, the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitter, cannot meet its environmental goals without connecting its abundant sources of renewable energy with its coastal megacities. By 2030, it plans to have enough solar and wind capacity to generate 1,200 gigawatts (GW) — equivalent to all of the US’ power needs.

Illustration: Mountain People

To hook that up to the grid, it is investing in a national network of power lines that by one estimate could take 30 years and cost US$300 billion, compared with the 10-year, US$65 billion allocation to grid infrastructure passed by the US Congress.

The growing number of lines crisscrossing the country from one massive pylon to the next are expensive, noisy and, to many, a blight on the landscape. However, most countries share China’s predicament. The best places to harvest wind and solar power are far away from the people who need it.

As of now, UHV lines are the only solution, and most economies are woefully behind. Brazil is the only other country to have such fully functioning lines — just two, built by a Chinese firm. China has 30.

“If you want cheap, secure and clean power, I don’t know how you get there without UHV power lines,” said Michael Skelly, a senior adviser at asset manager Lazard Ltd in Houston and a founder of Grid United LLC, a US energy infrastructure firm.

The problem is distance and storage. Coal mining also usually takes place far from urban centers, but coal and other fossil fuels can be shipped to power stations closer to cities. The power itself only travels a short distance.

That does not work with renewables. Wind and sunshine cannot be loaded onto trucks for delivery elsewhere.

Transmitting those electrons over thousands of kilometers requires direct current lines, the bigger the better. The higher the voltage, the less power is lost incrementally along the way. The UHV lines that run from Qinghai, Xinjiang and Yunnan to Beijing, Chongqing and Jiangsu carry the equivalent of 10 power plants’ worth of electricity. That is why they have to be strung so high off the ground.

It is also why they are noisy. The electricity field breaks apart air molecules, which makes that perpetual zzzzz sound.

Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) in October announced a collection of solar and wind projects, the first phase of which is to add about 100GW of power, or enough to supply Mexico’s electricity needs. Of the six interior regions that have been tapped to house a new crop of wind and solar farms, Qinghai has critical advantages. It is windy, bright and sparsely populated. It is also the origin of the Yellow River.

On a late September day, hydro station deputy chief Yang Xueli stood overlooking the Longyangxia Dam, a hydroelectric power station with an integral role to play in China’s grid. There was not a cloud in the sky — Qinghai is one of China’s sunniest provinces — and the water looked green in the midday light.

Fields of solar panels are not far, making this home to the world’s largest combined solar and hydroelectric facility.

“Water and light complement each other,” Yang said. “When light is intermittent, we adjust with hydro power.”

Even in dry, sunny places like Qinghai, the weather can be unpredictable, and the energy generated by sunlight varies depending on the conditions. Power from the dam is reliable, ensuring the UHV line can carry a full load of electricity.

As technology evolves, energy from renewables are to supplant the need for coal, Yang said.

The facility spans about 600km2, roughly the size of Singapore. When the station begins production, it is expected to generate some 18.7GW of electricity, equivalent to all of Israel’s power needs or twice New Zealand’s. That is more than enough for the 6 million residents of Qinghai, which earlier this year became China’s first province to run on renewable power for a full month.

The cables themselves are agnostic. As of now, most of the electricity they carry is still derived from coal-fired power plants. China has pledged that all new, cross-province power lines would transmit at least 50 percent renewable power, according to a government roadmap published in October, which lays out how it plans to cap carbon emissions by 2030.

Two companies are to be responsible for the build-out. The nation’s dominant electricity supplier, government-owned State Grid, has announced a US$350 billion expansion through 2025 that includes — but does not break out — UHVs.

It has 26 lines in operation, five under construction and another seven planned for the next three years. By then, all of State Grid’s cross-province UHV lines are to carry at least 50 percent clean energy, according to its plan for reaching the nation’s carbon goals published in March.

China Southern Power Grid Co, the other major operator, has four UHV lines and plans to spend just over US$100 billion on expanding its network through 2025, although it did not detail its specific investment in UHV.

Both grid operators declined interview requests for this story, and the National Energy Administration, which is expected to publish its latest five-year plan for the power grid this month, could not be reached for comment.

There are other expected winners, too: wind and solar firms that already dominate global renewable energy; makers of grid and power storage equipment; and the commodity traders who supply the copper that is used to conduct electricity.

Shanghai-traded shares of Nari Technology Co, the equipment-making subsidiary of State Grid, more than doubled in the past year and are poised to keep climbing, analysts said. Component manufacturer Sieyuan Electric Co, power distributor State Grid Information & Communication, and transformer maker TGOOD Electric are favored to outperform.

Detractors do not like the cost of the UHV network, and it is possible as-yet undeveloped technology could cut short the return on the significant investment. China’s lines have also suffered from low utilization rates. Grid operators and the government are trying to synchronize the development of new power generation with the construction of UHV lines that are to accommodate a larger portion of clean energy, Bejing-based BloombergNEF analyst Lin Wang said.

There is no shortage of demand. Several global companies that operate in China have set hard deadlines for using 100 percent clean energy, Hong Kong-based Lantau Group analyst David Fishman said.

“If you’re in southern or eastern China, and you have ever-increasing renewable energy demand, but are limited by your ability to install, UHV is your only access to renewables,” he said.

In the US, where massive power outages have grown more frequent and widespread in the past few years, similar efforts to establish a national grid have foundered. Skelly founded Clean Line Energy in 2009 and raised US$100 million to plan five UHV lines to carry wind power from the Great Plains to cities thousands of kilometers away.

The lines were popular with wind farm developers in Oklahoma and Kansas, and offered power to major cities like Memphis at rates lower than what they were paying to nearby coal plants.

However, the lines faced opposition from landowners and state regulators along the routes, and the resulting delays eventually forced Clean Line to sell off the projects and fold.

This is a common roadblock for UHV projects. Because the lines are so long and deliver few tangible benefits to the towns along the way, it is easy for projects that need incremental, local approvals to stall. People in China’s fly-over towns do not love the plans to put massive electrified towers in their midst, but Beijing has prioritized net-zero goals, and the projects have pushed through.

A 28-year veteran of China’s power industry, Yang lives in a nearby compound that houses about 100 dam workers, mostly men. The dam, he says, is critical for irrigation in the Yellow River basin and, along with solar, to the steady supply of clean energy that is expected to protect the environment in the long run.

Yang’s facility could one day become a feeder for a regional grid, or a global one. Given regional politics and individual countries’ domestic concerns, the idea seems like a long shot. However, several cross-border projects are in development in Europe and Asia. Earlier this year, Skelly founded a new company dedicated to long-haul, high-voltage transmission of renewable power.

“It’s not like we’re going to decide overnight, ‘Let’s make a global grid,’” he said. “When they laid the first trans-Atlantic telegraph cable, they weren’t planning to connect the whole world, but you turn around 100 years later and the whole world is connected.”

There are moments in history when America has turned its back on its principles and withdrawn from past commitments in service of higher goals. For example, US-Soviet Cold War competition compelled America to make a range of deals with unsavory and undemocratic figures across Latin America and Africa in service of geostrategic aims. The United States overlooked mass atrocities against the Bengali population in modern-day Bangladesh in the early 1970s in service of its tilt toward Pakistan, a relationship the Nixon administration deemed critical to its larger aims in developing relations with China. Then, of course, America switched diplomatic recognition

The international women’s soccer match between Taiwan and New Zealand at the Kaohsiung Nanzih Football Stadium, scheduled for Tuesday last week, was canceled at the last minute amid safety concerns over poor field conditions raised by the visiting team. The Football Ferns, as New Zealand’s women’s soccer team are known, had arrived in Taiwan one week earlier to prepare and soon raised their concerns. Efforts were made to improve the field, but the replacement patches of grass could not grow fast enough. The Football Ferns canceled the closed-door training match and then days later, the main event against Team Taiwan. The safety

The Chinese government on March 29 sent shock waves through the Tibetan Buddhist community by announcing the untimely death of one of its most revered spiritual figures, Hungkar Dorje Rinpoche. His sudden passing in Vietnam raised widespread suspicion and concern among his followers, who demanded an investigation. International human rights organization Human Rights Watch joined their call and urged a thorough investigation into his death, highlighting the potential involvement of the Chinese government. At just 56 years old, Rinpoche was influential not only as a spiritual leader, but also for his steadfast efforts to preserve and promote Tibetan identity and cultural

Former minister of culture Lung Ying-tai (龍應台) has long wielded influence through the power of words. Her articles once served as a moral compass for a society in transition. However, as her April 1 guest article in the New York Times, “The Clock Is Ticking for Taiwan,” makes all too clear, even celebrated prose can mislead when romanticism clouds political judgement. Lung crafts a narrative that is less an analysis of Taiwan’s geopolitical reality than an exercise in wistful nostalgia. As political scientists and international relations academics, we believe it is crucial to correct the misconceptions embedded in her article,