The global consumer goods industry’s plans for dealing with the vast plastic waste it generates can be seen in a landfill on the outskirts of Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta, where a swarm of excavators tears into stinking mountains of garbage.

These machines are unearthing garbage to provide fuel to power a nearby cement plant. Discarded bubble wrap, take-out containers and single-use shopping bags have become one of the fastest-growing sources of energy for the world’s cement industry.

The Indonesian project, funded in part by Unilever PLC, maker of Dove soap and Hellmann’s mayonnaise, is part of a worldwide effort by big multinationals to burn more plastic waste in cement kilns.

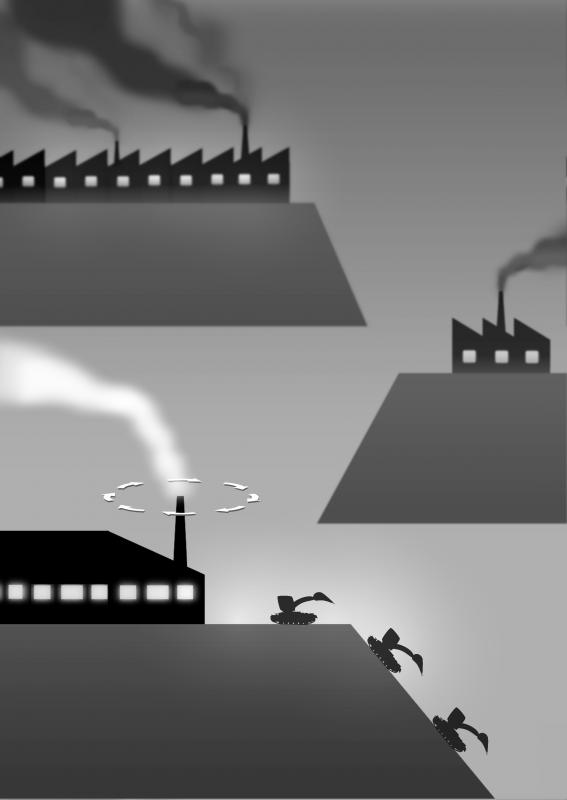

Illustration: Yusha

This “fuel” is not only cheap and abundant, it is the centerpiece of a partnership between consumer products giants and cement companies aimed at burnishing their environmental credentials. They are promoting this approach as a win-win for a planet choking on plastic waste. Converting plastic to energy, these companies said, keeps it out of landfills and oceans while allowing cement plants to move away from burning coal, a major contributor to global warming.

Nine collaborations have been launched over the past two years between various combinations of consumer goods giants and major cement makers. Four leading sources of plastic packaging are involved: Coca-Cola, Unilever, Nestle SA and Colgate-Palmolive.

On the cement side of the deals are four top producers: Switzerland’s Holcim Group, Mexico’s Cemex SAB de CV, PT Solusi Bangun Indonesia Tbk (SBI) and Republic Cement & Building Material Inc, a company in the Philippines.

These projects span the world, from Costa Rica to the Philippines, El Salvador to India.

The alliances come as the cement industry — the source of 7 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions — is facing rising pressure to reduce these greenhouse gases. Meanwhile, consumer brands are feeling the heat from lawmakers who are banning or taxing single-use plastic packaging and pushing so-called polluter-pays legislation to make producers bear the costs of its clean up.

Critics have said that there is little that is green about burning plastic, which is derived from oil, to make cement. A dozen sources with direct knowledge of the practice — among them scientists, academics and environmentalists — said that plastic burned in cement kilns emits harmful air emissions and amounts to swapping one dirty fuel for another.

More importantly, environmental groups said, it is a strategy that could potentially undercut efforts spreading globally to boost recycling rates and dramatically slash the production of single-use plastic.

Such thinking is naive, said Axel Pieters, CEO of Geocycle, the waste-management arm of Holcim Group, one of the world’s largest cement makers and partner with Nestle, Unilever and Coca-Cola in plastic-fuel ventures.

Pieters said that burning plastic in cement kilns is a safe, inexpensive and practical solution that can dispose of huge volumes of this trash quickly. Less than 10 percent of all the plastic ever made has been recycled, in large part because it is too costly to collect and sort. Meanwhile, plastic production is projected to double within 20 years.

“Thinking that we recycle waste only, and that we should avoid plastic waste, then you can quote me on this: People believe in fairy tales,” Pieters said.

Unilever would not comment specifically on the Indonesia project. It said in an e-mail that in situations where recycling is not feasible, it would explore “energy recovery initiatives.” That is industry parlance for burning plastic as fuel.

Coca-Cola, Unilever, Colgate and Nestle did not respond to questions about the environmental and health impacts of burning plastic in cement kilns. The companies said they invest in various initiatives to reduce waste, including boosting recycled content in their packaging and making refillable containers.

Cemex, SBI, Republic Cement and Holcim’s Geocycle unit said that their partnerships with consumer goods firms were aimed at addressing the global waste crisis and reducing their dependence on traditional fossil fuels.

Exactly how much plastic waste is being burned in cement kilns globally is not known. That is because industry statistics typically lump it into a wider category called “alternative fuel” that comprises other garbage, such as scrap wood, old vehicle tires and clothing.

The use of alternative fuel has risen steadily in the past few decades and is the dominant energy source for the cement industry in some European countries.

There is no question that the amount of plastic within that category has increased and should keep climbing given a worldwide explosion of plastic waste, 20 cement industry players interviewed for this report said, including company executives, engineers and analysts.

Reuters also reviewed data from cement associations, individual countries and analysts that confirmed this trend.

For example, Geocycle uses 2 million tonnes of plastic waste per year as alternative fuel at Holcim plants worldwide, Peters said, adding that the company intends to increase this to 11 million tonnes by 2040, including through more partnerships with consumer goods companies.

Pieters said the cement industry has the capacity to burn all the plastic waste the world produces. The UN Environment Programme estimates that figure to be 300 million tonnes annually. That dwarfs the world’s plastic recycling capacity, estimated to be 46 million tonnes a year, said a 2018 estimate by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, a global policy forum.

Meanwhile, plastic pollution is bedeviling communities whose landfills are reaching capacity and despoiling the Earth’s wild places. Plastic garbage flowing into the oceans is due to triple to 29 million tonnes a year by 2040, a Pew Charitable Trusts study said last year. This detritus is endangering wildlife and contaminating the seafood humans consume.

“The cement industry is definitely a solution,” Pieters said.

TOXIC EMISSIONS

Consumer goods giants are turning to cement firms for help reduce plastic litter as other initiatives stumble. Reuters reported in July that a set of new “advanced” plastic recycling technologies promoted by big brands and the plastic industry had suffered major setbacks around the world.

Cement-making is one of the world’s most energy-intensive businesses. Fuel — mainly coal — is its single-biggest expense, industry executives said. In the 1970s, producers looking to reduce costs began stoking kilns with garbage such as tires, biomass, sewage sludge — and plastic. Those materials are not as efficient as coal, but are virtually free. Some local governments even pay cement makers to take this waste.

In Europe, refuse makes up roughly half the fuel used by the cement industry. In Germany, the bloc’s biggest producer, the ratio is 70 percent, according to 2019 data from the Global Cement & Concrete Association (GCCA), a London-based trade organization. The US uses 15 percent alternative fuel in its kilns, said the Portland Cement Association, a US industry group. Spokesperson Mike Zande said its members have the capacity to catch up with Europe.

While cost-cutting remains the primary driver, the industry in the past few years has begun touting its garbage fuel as a way to reduce the “societal problem” of plastic waste, said Ian Riley, CEO of the London-based World Cement Association (WCA), which represents producers in developing countries.

So it was logical that cement makers would team up with consumer goods companies, the largest source of single-use plastic packaging, in the partnerships to burn discarded plastic in their kilns.

In emerging markets, big brands sell a slew of food and hygiene products packaged in plastic sachets, typically single-serving portions tailored to the budgets of poor households. Billions of these flexible pouches are sold each year. Sachets are nearly impossible to recycle because they are made of layers of different materials laminated together, usually plastic and aluminum, that are difficult to separate.

Indonesia, an archipelago of more than 270 million people, is the second-largest contributor to ocean plastic pollution behind China, partly due to its widespread use of sachets, a 2015 study published in the journal Science said.

Plastic garbage can be seen everywhere around Jakarta, a city of more than 10 million people. It clogs storm drains, litters its teaming slums and mars its shoreline.

Developing countries have generally welcomed assistance with waste management. Thus Indonesia was a natural location for Unilever’s waste-fuel venture with cement maker SBI and the local Jakarta government. At last year’s launch, Jakarta Environment Agency head Andono Warih praised the initiative and expressed hope that it would spark other such collaborations.

The project uses plastic that has been buried in the region’s Bantar Gebang landfill, one of the largest dumps in Asia. Waste excavated by earth-moving equipment is transported to a warehouse at the landfill site. There, it is shredded, sieved and dried into a brown mix resembling manure. That material, known as refuse derived fuel (RDF), is then fed into the kiln at an SBI cement plant in Narogong, just outside Jakarta.

SBI uses 20 percent RDF at that plant, a figure that could increase to 35 percent, SBI business development manager Ita Sadono said.

The operation still relies primarily on coal, she said, adding that RDF is “significantly helping to reduce plastic waste.”

Unilever is helping to fund a second RDF project in Cilacap, an industrial region in Central Java, SBI and a sustainability report last year by Unilever’s Indonesian unit said. The two facilities could send 30,000 tonnes of plastic waste per year to SBI’s cement plants, an analysis of data provided by SBI showed.

About 2km from SBI’s cement plant near Jakarta, Dadan bin Anton, 63, runs a roadside stall selling plastic sachets of soap, washing powder and instant coffee, including brands owned by Unilever.

He said that he often has trouble breathing and blames the cement plant.

“People here are breathing dust every day,” he said.

SBI has invested in mitigation measures to cut dust at its plants, Sadono said, and it is not clear whether the cement facility has anything to do with Dadan’s burning chest.

Jakarta boasts some of the dirtiest air in Asia. Pollutants from industry smokestacks, agricultural fires and auto exhaust routinely blanket the city.

However, some scientists have said that incinerated plastic is a dangerous new ingredient to add to the mix, particularly in developing nations where air-quality rules often are weak and enforcement is spotty.

Plastic releases harmful substances, such as dioxins and furans, when burned, said Paul Connett, a retired professor of environmental chemistry and toxicology at St Lawrence University in Canton, New York, who has studied the poisonous byproducts of burning waste.

If enough of those pollutants escape from a cement kiln, they can be hazardous for humans and animals in the surrounding area, Connett said.

Such fears are overblown, said Claude Lorea, cement director at GCCA, the industry group representing big cement firms including Holcim and Cemex.

She said super-heated kilns destroy all toxins resulting from burning any alternative fuel, including plastic and hazardous waste.

However, things can go wrong.

In 2014, a cement plant in Austria released hexachlorobenzene (HCB), a highly toxic substance and suspected human carcinogen, after the facility burned industrial waste contaminated with the pollutant. Cheese and milk sourced from cattle raised near that plant in southern Carinthia state were tainted, Austria’s health and food safety agency found. Blood samples drawn from area residents also contained HCB, which can damage the nervous system, liver and thyroid.

An investigation commissioned by the state government found multiple failures by local regulators and the cement plant, including that the kiln was not running hot enough to destroy contaminants such as HCB.

The Austrian cement maker that operates the plant, w&p Zement GmbH, said that it had worked to eliminate all the environmental pollution from the incident and that it had provided help to the community, such as replacing contaminated animal feed.

Carinthia spokesperson Gerd Kurath said in an e-mail that the government’s continued monitoring of air, soil and water samples in the area shows that contamination levels have declined.

Meanwhile, the cement industry is heralding waste-to-fuel as a way to fight global warming.

That is because burning refuse, including plastic, emits fewer greenhouse gases than coal, the GCCA trade group said.

Burning garbage “reduces our fossil fuel reliance,” Lorea said. “It’s climate neutral.”

The European Commission, which sets emission rules in Europe, said that plastic does emit fewer carbon dioxide emissions than coal, but more than natural gas, another fuel used by the cement industry.

The US Environmental Protection Agency, which regulates environmental policy in the world’s largest economy, reached a different conclusion. It said in a statement there is no significant climate benefit to be gained from substituting plastic for coal, and that burning this waste in cement kilns can create harmful air pollution that must be monitored.

Measuring plastic’s carbon dioxide emissions against those of coal, the world’s dirtiest fossil fuel, is not the benchmark to use if the cement industry is serious about fighting global warming, said Lee Bell, adviser to the International Pollutants Elimination Network, a global coalition working to eliminate toxic pollutants.

Reducing the industry’s massive carbon emissions, he said, requires a switch to fuels such as green hydrogen, a more expensive but low-polluting fuel produced from water and renewable energy.

“The cement industry should leap-frog the whole burning-waste paradigm and move to clean fuel,” Bell said.

The GCCA said that the industry is improving energy efficiency and is considering the use of green hydrogen.

EVER MORE PLASTIC

While cement plants in industrialized countries are gearing up to burn more plastic, explosive growth is anticipated in the developing world.

China and India together account for 60 percent of the world’s cement production in facilities whose primary fuel is coal. These countries have set targets of using alternative fuel to stoke 20 percent to 30 percent of their output over the next decade.

If they reached just a 10 percent threshold, that would equate to burning 63 million tonnes of plastic annually, up from 6 million tonnes now, the Norwegian scientific research group SINTEF said. That is more plastic waste than the US generates each year.

In 2019, 170 countries agreed to “significantly reduce” their use of plastic by 2030 as part of a UN resolution. However, that measure is non-binding, and a proposed ban on single-use plastic by 2025 was opposed by several member states, including the US.

Thus the waste-to-fuel option might well become an unstoppable juggernaut, said Matthias Mersmann, chief technology officer at KHD Humboldt Wedag International AG, a German engineering firm that supplies equipment to cement plants worldwide.

Plastic waste is quickly outstripping countries’ capacity to bury or recycle it. Burning it eliminates large amounts of this material quickly, with few special handling or new facilities required. There are an estimated 3,000 or more cement plants worldwide. All are hungry for fuel.

“There’s only one thing that can hold up and break this trend, and that would be a very strong cut in the production of plastics,” Mersmann said. “Otherwise, there is nothing that can stop this.”

That momentum has some environmentalists worried, including Sander Defruyt, who heads a plastics initiative at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a UK-based nonprofit focused on sustainability. The foundation in 2018 worked out waste-reduction and recycling targets with Coca-Cola, Nestle, Unilever, Colgate-Palmolive and hundreds of other consumer brands.

Defruyt said the foundation does not support its partner companies’ pivot toward incineration.

Burning plastic for cement fuel, he said, is a “quick fix” that risks giving consumer goods companies the green light to continue cranking out single-use plastic and could reduce the urgency to redesign packaging.

“If you can dump everything in a cement kiln, then why would you still care about the problem?” Defruyt said.

Coca-Cola, Nestle, Unilever and Colgate-Palmolive said their cement partnerships are just one of several strategies they are pursuing to address the waste crisis.

PLASTIC PRAYERS

In the central England village of Cauldon, residents have complained in the past few years to the local council and Britain’s environmental regulator about noise, dust and smoke coming from a nearby cement plant owned by Holcim. Those efforts have failed to derail the expansion of that facility to burn more plastic.

When completed next year, alternative fuel, including “non-recyclable” plastics such as potato chip bags, will account for up to 85 percent of the facility’s fuel, planning documents filed with local authorities showed.

The move could recover energy from plastic waste otherwise destined for landfills, the documents said.

Cauldon resident Lucy Ford, 42, said the cement maker’s plans have only added to some villagers’ fears about emissions.

“They say they are the answer to all of our plastic prayers,” she said. “I don’t like the idea of it.”

Pieters said that he understood the community’s concerns.

He said the company complies with local regulations and that it carefully monitors the plant’s emissions, which would be lowered by the upgrades.

The British Environment Agency said in an e-mail that it took all complaints about the plant seriously.

It said the Cauldon facility has a permit to burn waste and that the plant has to comply with its regulations.

In Indonesia, Unilever and SBI said that using plastic for energy was preferable to leaving it in a landfill.

Local environmentalists said that they are alarmed that cement kilns could be shaping up as the fix for a nation flooded with plastic waste.

It would allow consumer brands to continue business as usual, while adding to Indonesia’s air-quality woes, said Yobel Novian Putra, an advocate with the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, a coalition of groups working to eliminate waste.

“It’s like moving the landfill from the ground to the sky,” Putra said.

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

I have heard people equate the government’s stance on resisting forced unification with China or the conditional reinstatement of the military court system with the rise of the Nazis before World War II. The comparison is absurd. There is no meaningful parallel between the government and Nazi Germany, nor does such a mindset exist within the general public in Taiwan. It is important to remember that the German public bore some responsibility for the horrors of the Holocaust. Post-World War II Germany’s transitional justice efforts were rooted in a national reckoning and introspection. Many Jews were sent to concentration camps not